The Memory Chalet

By Tony Judt | Penguin | $36.95

FOR months, night after night, he would sit in the lounge of a pensione in the Swiss village of Chesieres. To pass the time he would round up his stray thoughts like a butterfly collector armed with a net.

Stretched out comfortably in an armchair, he would scroll back and forth across the episodes of his life, ordering and re-ordering his recollections, following a line of inquiry until it coalesced into a shape that pleased him. When he was satisfied, he would get up and go to the front door of the chalet. And then he would begin the difficult task of remembering what he had remembered.

He might start by uttering a possible opening sentence to the skis stacked dripping in the entrance hall. (“For me the word ‘chalet’ conjures up a very distinctive image.”) Moving up the stairs he might note an important twist in the narrative to the cuckoo clock at the reception desk. Gliding from lounge to dining room to bedroom, through this strangely unpopulated hotel, he would murmur into a cupboard, at a lamp, to a shelf of books. In this way he would chase down the words, and pin down the paragraphs, that he needed.

And then he’d wake up – in an apartment just off Washington Square in Manhattan, a breathing device strapped tightly to his nose, his rag-doll body as still as if he were a monarch lying in state.

But he had what he wanted – another memory distilled in a piece of prose, all laid out inside his head.

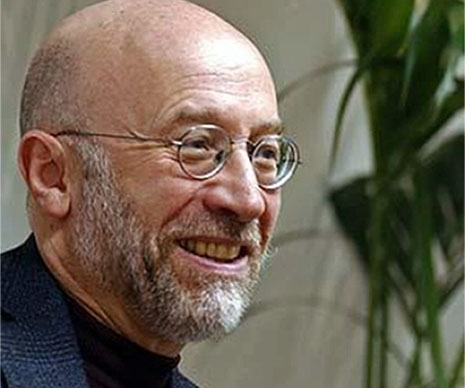

TONY JUDT was an acclaimed historian; a skilled polemicist; and a dedicated teacher. He wrote or edited over a dozen books, including the international bestseller Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945. He contributed regularly to journals like the New York Review of Books, and ran New York University’s Remarque Institute, which is dedicated to the study of Europe. As that old-fashioned beast, a public intellectual, he wrote with erudition about subjects as varied as the legacy of Primo Levi, the irredeemable flaws of Marxism, and the American liberals who supported the Iraq war, a group he dubbed “George Bush’s useful idiots.” He didn’t much like communism, thought that social democracy was worth pursuing, and wasn’t too impressed by political correctness in academia.

Most controversially of all, this teenage Zionist became a tough critic of Israel. In 2003 he published an essay arguing that the two-state solution was dead and that Israel would have to become bi-national to survive - with Jews and Palestinians living together as full citizens within the one set of borders.

Judt took being an intellectual seriously; he didn’t mind losing friends or making enemies. Whatever he wrote he always generated a lot of letters to the editor. And then one day he noticed he was having trouble hitting the correct keys on his computer. It was the beginning of the end.

In September 2008 he was diagnosed as suffering from a motor neuron disorder, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, more commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. The cells that controlled his body’s movements were dying off. At first it was just the tips of his fingers that wouldn’t respond to his brain’s orders; then his limbs became recalcitrant; then his larynx; then his lungs. There was no pain, thankfully – but as he still possessed the sensation of touch, he was tortured by itches he couldn’t scratch and the endless discomfort of not being able to move. Eventually he was fitted with a BiPAP breathing device and a small microphone that served to amplify his weakened voice.

The nights were particularly hard. Helped into his cot, he would be sat upright, wedged into place with pillows and wrapped in a blanket. Finally his glasses would be removed and he was ready to face the long hours ahead: “and there I lie, trussed, myopic, and motionless like a modern day mummy, alone in my corporeal prison, accompanied for the rest of the night only by my thoughts.”

As his body shut down, Judt’s intellect remained as sharp as ever – and conscious of every spadeful of earth, as he was slowly buried alive. By October 2009 he was almost entirely paralysed from the neck down. On 6 August 2010 the disease finally crushed the life out of him. He was sixty-two.

AFTER his diagnosis Judt spent some time absorbing its full meaning. A lesser man might have given in to despair and called for the morphine then and there, but within a few months he was back at work.

As a boy in the late 1950s Judt holidayed with his family for a week at a small hotel in the Swiss Alps. He barely gave the place another thought for the next fifty years, but when he fell ill Judt discovered that he had a very clear and precise recall of its layout. He soon put it to good use.

From his extensive reading in history, Judt knew of a mnemonic device. As Jonathan Spence explains in his book, The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci, early-modern thinkers and Renaissance travellers developed systems to store and retrieve their thoughts and experiences by training their brains to access and order memories using an imagined three-dimensional space, such as a palace.

By associating a sentence or paragraph of prose with some distinctive part of his “memory chalet,” Judt was able to “write.” After a long night thinking, arranging and remembering, Judt would then dictate the finished product to a transcriber in the morning.

From these nocturnal excursions through the re-imagined site of a boyhood holiday, he was able to carry on doing what had driven him since the age of twelve, when he first hatched the desire to become a historian. He managed to draft, and deliver, a lecture at New York University on the future of social democracy. He turned this lecture into a book: a sort of political last will and testament called Ill Fares the Land. And somehow he also found the energy to write The Memory Chalet, something quite new and unexpected in Judt’s literary output.

Judt calls the short pieces that make up the book feuilletons: part essay, part memoir, they are personal in a way that he never attempted before in his career. And Judt felt lucky to have them. “To fall prey to a motor neuron disease is to surely have offended the Gods at some point, and there is nothing to be said,” he writes, “But if you must suffer thus, better to have a well-stocked head: full of recyclable and multi-purpose pieces of serviceable recollection.”

Better to be an intellectual with the disorder who has lived in his head for a living, Judt once argued in an interview, than a plumber or truck driver less well prepared to recline and become a hostage to your own thoughts.

Every night he had somewhere to go and something to do. He could catch a Green Line Bus across 1950s London; he could board the cross-channel ferry, the Lord Warden, and re-experience the excitement of travelling to postwar France with his parents; he could smell again the interior of one of his car-crazy father’s many Citröens or taste again his grandmother’s Friday night dinners of matzoh ball soup and gefilte fish. He could relive those “long, happy hours listening to Central European autodidacts arguing deep into the night,” their words tumbling from the kitchen table and into the Young Tony’s ears.

TONY JUDT was born in the East End of London in 1948. His father was a Jewish émigré, his mother a British-born Jew. Both worked as hairdressers and were socialists. Judt grew up a very clever but solitary boy. At twelve he would sometimes hang out at Waterloo Station until two in the morning, stretching out a mug of British Rail cocoa. He loved trains, but he was never a train-spotter: “this seemed to me the most asinine of static pursuits – the point of a train was to get on it.”

When his parents got a bit of money they moved to middle-class Putney and Judt went to a posh school, where, not surprisingly, he didn’t really fit in. He became a Zionist, lived on a kibbutz, went up to Kings College, Cambridge, and set off on a garlanded academic career as a historian. He became a Marxist. He demonstrated in 1968. He stopped being a Marxist. He studied in France; taught in California. He wrote books about the French Left and French intellectual life.

After his second marriage broke up he had the traditional mid-life crisis, but instead of buying a bright red Citröen, like his father might have done, he learnt Czech and became a respected commentator on Eastern Europe. Then he moved to New York and became an essayist of note and a popular historian. And found love with wife number three, and began a family.

The Memory Chalet recalls all this and more with such light wit and knowing nostalgia that you cannot quite believe the circumstances under which it was composed.

PERHAPS strangely for a left-wing Jew, Judt maintained an unfashionable, and life-long, love of Switzerland. “One is not supposed to love Switzerland,” he writes in the book’s final piece, “Expressing affection for the Swiss or their country is akin to confessing nostalgia for cigarette smoking or The Brady Bunch.”

Fully cognisant of its role as a financial enabler to Nazi Germany, Judt nevertheless loved Switzerland for its order, its peacefulness and the family memories that he associated with it. And Judt being Judt he loved Switzerland for its trains.

In the Alpine town of Mürren - where he stayed once at the chalet with his parents, and many years later with his two sons - Judt loved the “clockwork arrival and departure of the little single carriage train that wends its way around the mountainside.” In the last months of his life he thought of that train in Mürren - “punctual, predictable and precise to the second” – and found some comfort in remembering and replaying in his mind its dependable climb and descent.

“We cannot choose where we start out in life, but we may finish where we will,” run the very last words of The Memory Chalet, “I know where I shall be: going nowhere in particular on that little train, forever and ever.” •