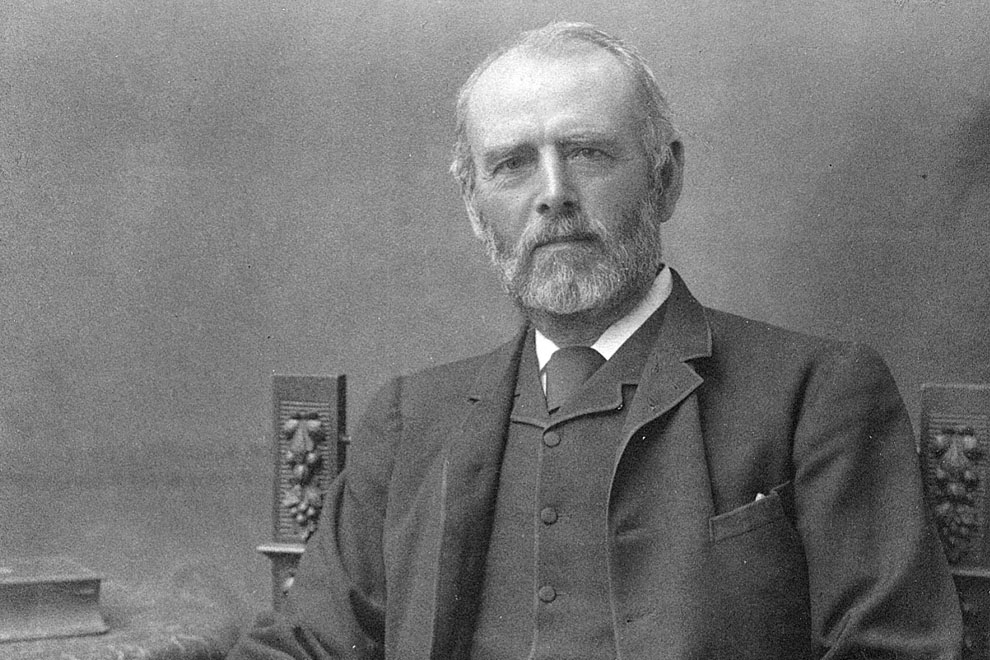

David Syme: Man of the Age

By Elizabeth Morrison | Monash University Publishing and State Library of Victoria | $39.95

Drawing on new technologies of production and distribution, newspapers were the dominant medium of commerce and politics in nineteenth–century Australia. They grew from small, precarious enterprises to enormously profitable undertakings with mass circulations and a corresponding influence. And among their proprietors, none matched the ambition of David Syme or his success with the Age. He built the Melbourne daily into the dominant Australian newspaper of the late nineteenth century, with a circulation far in excess of any other daily, and he made it a vital force in Victorian politics.

There have been two biographies of Syme. The first, by Ambrose Pratt, was an in-house account, largely dictated by its subject, which appeared in 1908, the year after his death. Edward Sayers, the author of the second, was also an Age journalist. By no means uncritical, Sayers undertook substantial research but his main object was to soften the legend of a grim and harsh despot, a legend that was still current when his book appeared in 1965.

In the following year the Syme family entered into a partnership with their Sydney counterparts, the Fairfaxes. The Fairfax holding increased until, in 1983, they acquired control. Meanwhile Keith Murdoch, who Syme in his final years had employed as a suburban correspondent, had built up the morning Sun and the evening Herald into newspapers that eclipsed the Age, and his son subsequently gathered them up into his media conglomerate. The landmarks of Syme’s supremacy soon vanished. The handsome Collins Street premises of David Syme & Co. were first disfigured and then abandoned; the Melbourne Mansions he had constructed further up Collins Street, along with his family home in Kew, were demolished. The centenary of his death and the sesquicentenary of his principal newspaper both passed largely unrecognised.

Now, for the first time, we have a full biography and a close study of Syme’s business methods, not just as a newspaper proprietor but also as a property developer, landholder and investor, based on assiduous and no doubt painstaking archival research. The Syme family papers are held by the State Library of Victoria, but anyone who has pored over the faint copies of David Syme’s handwriting in the letterbooks that contain his outward correspondence will appreciate the labour involved in working through them. The inward correspondence was not kept and the business records are incomplete. The newspaper editions themselves are not digitised so perforce Elizabeth Morrison has had to read systematically through the Age and other papers Syme produced, though the weekly Illustrated Australian News and its variants are online. (While the National Library’s digitisation of newspapers makes it possible to search those included, it provides only one major daily for each city. That the National Library chose the Argus rather than the Age would have vexed Syme.)

As Morrison’s previous study of Victorian country newspapers, Engines of Influence, made clear, this was initially a trade with few barriers to entry. You could rent premises and acquire type and a flatbed press for a few hundred pounds. Much of the content could be exchanged or recycled, and advertising revenue would support income from sales. (For that reason, circulation figures were habitually padded.) With low capitalisation, growth came through diversification rather than acquisition, and Morrison draws our attention to the variety of titles that Syme launched alongside the Age.

Like other proprietors, he had no training in publishing. He joined forces with his brother Ebenezer, who had acquired the infant Age in 1856 with £2000 borrowed from fellow Scots. Ebenezer was a journalist; David had previously mined for gold in the Californian and Victorian fields, then worked as a contractor for public works, and continued to do so until his brother died in 1860. Thereafter he was responsible for the management, production and editing of three papers.

He added more titles and somehow managed to pay off creditors. Soon he was expanding and by 1872 he purchased the country’s first rotary press. With this and subsequent technological advances, he oversaw the installation of the machinery and solved the production problems. It was the same with the design and layout of the papers, the employment and supervision of the journalists, the determination of the editorial line. Proceeding by trial and error, working impossible hours, it was little wonder that he became such a driving and abrasive figure.

Morrison’s attention to the business of the newspaper is informed and informative. She shows the volatility of revenue and profit. Newspapers were highly susceptible to the fluctuations of a growing but exposed trading economy, and Syme’s championship of closer agricultural settlement and protection of local industry were meant to reduce this vulnerability. She has put together a nearly comprehensive account of the journalists whom Syme employed, and the extent to which he depended on them. She traces the expansion of coverage as Syme engaged interstate and international correspondents, the building up of cable news, the sponsoring of major events to increase the readership. Her judgement, that Syme was a remarkably successful innovator until others passed him by – in part because of his age, in part because of his inability to delegate – is persuasive.

Beyond the newspaper business, Morrison provides new information on Syme’s other enterprises. We see him buying and selling property as soon as he had the means to do so, and investing in mining and other ventures. Morrison enables us to grasp the scale of this activity and also its logic: he was not a speculator, and the holdings were designed as a cushion against the fluctuations in his newspaper business. In later life he took up weekend farming and was able to settle family members on his properties.

There was nothing in Syme’s background that predisposed him to life on the land: his father and brothers lived by words and ideas, instructing others. The father, an austere and strict patriarch who withheld affection, was a schoolmaster in North Berwick, a small town on the Firth of Forth. Syme would recall that his father’s love “seemed entirely overshadowed by his sense of duty, and he asked nothing from us except obedience.” This passage comes from an extended memoir that Syme set down at the end of his life. Pratt reproduced substantial passages in his biography; Morrison points out that it does not tell the whole truth, but it is nevertheless a pity that she did not do the same, for the memoir has a compelling force.

Her treatment of the family’s tribulations suffers from a lack of familiarity with Scottish history, especially its religious history, which leads her to see Syme as marked by a Calvinist austerity. Syme’s father was certainly a strict Calvinist, at odds with the local Church of Scotland minister whose laxity was symptomatic of the established church by this time. Such worldliness would give rise in 1843 to the Disruption and the formation of a more rigorous Free Church, but Syme and his siblings did not follow that path. Theirs was a fundamentally different turn, to the theology of the Evangelical Union, which broke decisively from Calvin’s doctrine of the elect to an insistence on salvation by faith.

David, the youngest of the family, followed his brothers George and Ebenezer to a seminary of the Evangelical Union. The elder brothers subsequently ministered to Baptist and Unitarian churches but could not settle. His intellectual formation was similar: the rationalism of the Scottish Enlightenment and the yearning for spiritual comfort, the rejection of dogma and the desire to believe, the suspicion of authority and the need to impose order. He was the outcast, for he lost his vocation, yet he was also the anointed one. He came first to the promised land, made good and admitted the reassembled family to his patrimony.

To do so, however, he had to wrest his brother Ebenezer’s share of the Age from his widow Jane and her children. Since Ebenezer had died intestate, the partnership with Jane had to be negotiated and renegotiated. She returned to England in 1862, taking with her a half share and the dark secret of a new partner and pregnancy, while David chafed for ownership of the enterprise he was building. Fifteen years later, when he discovered her remarriage, he browbeat her into selling her share but had to concede a quarter-share to her son Joseph, who assumed responsibility for the printing side of the business until the fraught relationship with his uncle broke down and he was bought out for £140,000. Here is a tangled saga of money and morality worthy of Trollope; Morrison provides an authoritative and even-handed account.

Elizabeth Morrison’s declared purpose is to tell the story of the man behind the legend, placing him and his business firmly in the world of newspaper publishing, and she has succeeded admirably. The man of the legend is fully evident – domineering, self-righteous and censorious – and we see too his acts of contrition and personal generosity. Of particular interest is the clear evidence Morrison provides of Syme’s frailties. He was a worrier who often changed his mind, dwelt obsessively on minutiae, and created muddle and confusion with his mistrust and interference. She suggests that he might have developed a paranoid personality disorder, though he would not be the first newspaper tycoon to exhibit that trait.

“Those who come to this book for more insights into the political history of Victoria and Australia,” she warns at the outset, “may be disappointed.” The book deals perfunctorily with the great reform crusades of the Age, and its part in the two constitutional crises of the 1860s and 1870s. There is little on its stance during the great strikes of the 1890s, or on federation. The politicians who worked for him – Charles Pearson, Alfred Deakin and H.B. Higgins – appear, but not Syme’s influence on their political careers. Morrison is dubious of the claims that Syme made and unmade ministries, but she does not investigate further, and her observation that he had “many other matters to preoccupy him” than “attending to policy” is unpersuasive.

In giving us the man behind the legend, Morrison leaves his reign as King David untested. But any future assessment will have to draw on this rich and rewarding biography. •