Macular Disease Foundation Australia, or MDFA, a respected charity with $8 million in assets, describes itself as “the voice of the macular disease community.” It provides information to the public and to health professionals, offers advice to government, and advocates for greater support of treatment of eye diseases.

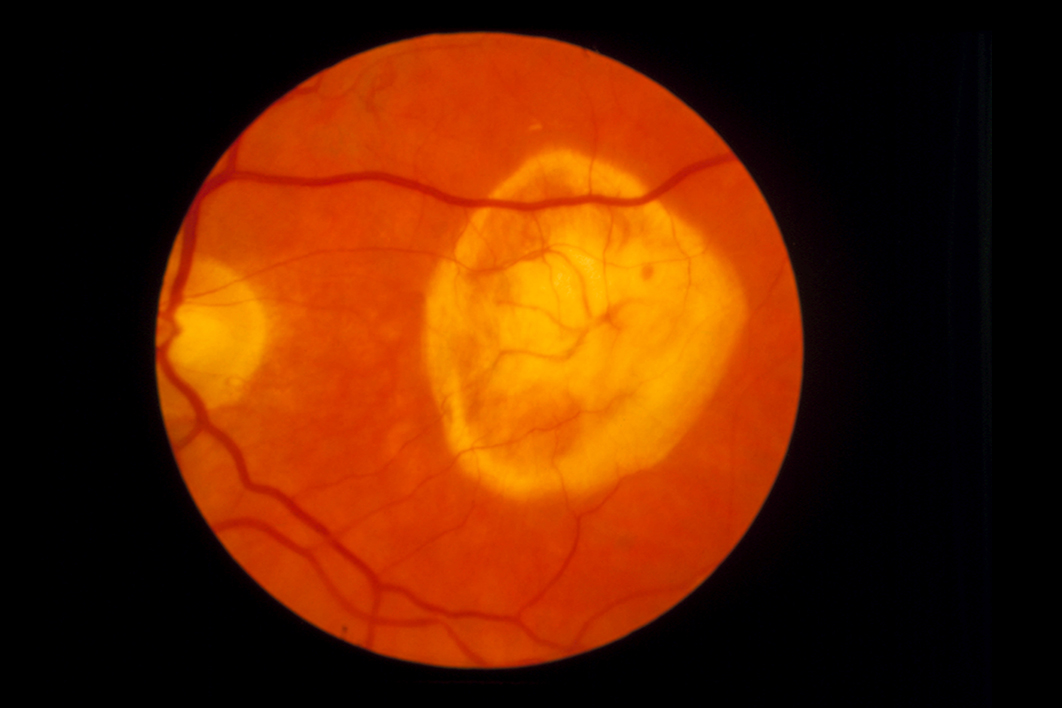

Diseases affecting the macula, the central part of the back of the eye, are common, especially in older people. In the past fifteen years two drugs, aflibercept and ranibizumab, have become available to treat these conditions. NPS MedicineWise, an independent organisation that aims to ensure people receive the best-value care for their individual circumstances, says they help some people with macular conditions maintain their sight, and are more effective than previous treatments such as laser surgery. Reviews of aflibercept and ranibizumab by Cochrane, the centrepiece of evidence-based medicine, come up positive. The drugs work.

But they are expensive. Last year the Australian government, through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, or PBS, spent $304 million on aflibercept, sold by Bayer Australia, and $200 million on ranibizumab, sold by Novartis. A total of more than $500 million on those drugs alone.

Recently, the Guardian reported research showing that pharmaceutical companies sponsored 230 consumer health organisations to the tune of $34.5 million between 2013 and 2016. This article dives into just one of those consumer health organisations, the MDFA, and its sponsorship by the pharmaceutical companies Bayer Australia and Novartis.

The publicly available records from MDFA’s annual reports and financial reports, along with the reports made by Bayer Australia and Novartis to their peak body, Medicines Australia, chart a symbiotic relationship between the charity and the pharmaceutical companies, and show the substantial benefits that have accrued to all players. The two companies were supported by Deloitte Access Economics, a Canberra-based consultancy that combines what it calls “deep economic rigour” with “practical commercial advice to help shape public policy.”

MDFA started life as the Macular Degeneration Foundation, or MDF, in 2001. Novartis was an early supporter. By 2004–05 MDF’s income had passed $1 million per year, with 58 per cent of its funds coming from corporate donations and sponsorship. Throughout its life, its main corporate supporters have been Novartis, Bayer Australia and the vitamin manufacturer Blackmores (there is some evidence that certain supplements help slow the progression of certain eye diseases).

In 2005–06, corporate support of MDF reached $880,000. It is not clear who donated the money or why — such matters were not reported publicly at that time. But in August 2007, ranibizumab was listed on the PBS, and in that financial year corporate support passed $1.2 million.

The PBS, incidentally, is a goldmine for pharmaceutical companies. There’s a good reason they make extraordinary efforts to get their products listed — last year, twenty-three separate products each earned their manufacturers more than $100 million from the PBS.

In 2009 and 2010, Novartis donated $2.285 million to MDF for it to run national print and television campaigns. Pharmaceutical companies aren’t allowed to advertise their products to the public, but they are allowed to have a third party like MDF advise people to have their eyes checked for conditions that their products can treat. And they are allowed to simultaneously promote their products to doctors and optometrists. And if more people have their eyes checked, and end up being prescribed their products, well…

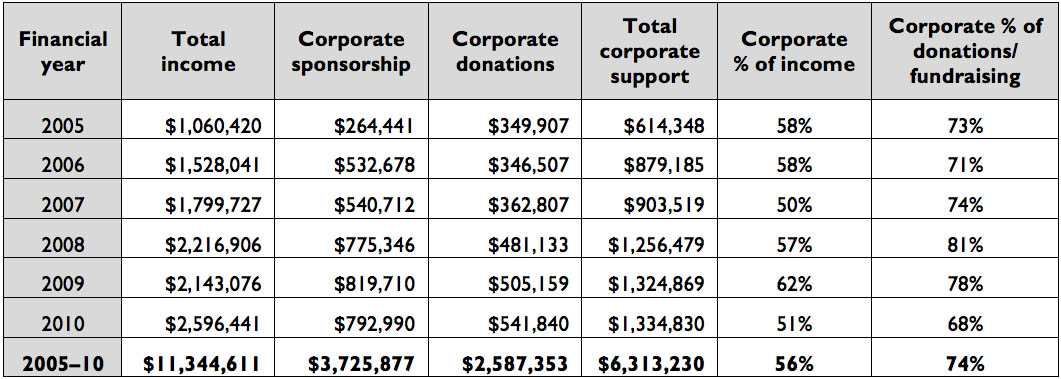

MDF’s income from corporate donations grew each year. Between 2004–05 and 2009–10, corporate donations and sponsorship made up 75 per cent of all donations and sponsorship, and 56 per cent of all income, as this table shows.

MDF’s income when corporate donations are treated separately (2004–05 to 2009–10)

Source: MDF/MDFA’s annual reports and financial statements complied by author

In October 2011 Deloitte Access Economics entered the conversation. It produced a report called Eyes on the Future: A Clear Outlook on Age-Related Macular Degeneration, which was co-branded with MDF. Inside the report, Novartis’s funding is acknowledged. The report found that vision loss associated with macular degeneration cost the health system $359 million in 2010, but that indirect costs of $389 million (for things like bringing forward the timing of a funeral) should be counted, as should almost $4.4 billion for loss of wellbeing. The report also found that if Novartis’s product, ranibizumab, was used to treat all Australians with the appropriate type of macular degeneration, the savings would be close to $1 billion in 2010.

Soon after this MDF changed its name to Macular Disease Foundation Australia to cover all diseases affecting the macula.

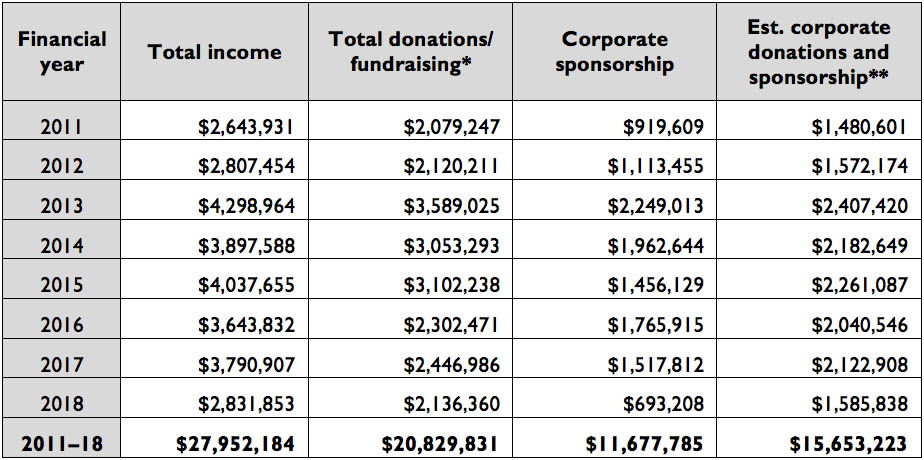

In December 2012 Bayer Australia successfully had its drug, aflibercept, also used to treat macular diseases, listed on the PBS. By this time, MDFA had changed the way it reported its financials, and some clarity was lost. Corporate donations were no longer treated separately, but were subsumed into the figures for total donations and fundraising. Corporate sponsorship was still recorded separately, though, and in that 2012–13 financial year it doubled from $1.1 million to $2.2 million, as this table shows.

MDF/MDFA’s income when corporate donations subsumed into other donations (2010–11 to 2017–18)

* In 2017–18, a corporate donation of $400,000 was noted. ** Based on corporate donations and sponsorship providing 56 per cent of income.

Source: MDF/MDFA’s annual reports and financial statements

The 2012–13 financial year was MDFA’s best year for corporate donations and sponsorships, with about $2.4 million coming in. Information on some of these corporate donations comes from the pharmaceutical companies’ obligations to provide information to the public. Like Novartis, Bayer is a member of Medicines Australia, the peak body of the pharmaceutical industry in Australia, and is obliged under its code of conduct to provide “a report listing health consumer organisations to which it provides financial support and/or significant direct/indirect non-financial support.”

Bayer says that in 2013 it “sponsored a range of projects to support macular disease patients. These included the provision of patient services and resources, the development of a new website, a Medicare Locals Pilot Program, a disease awareness campaign, research and policy projects and conference participants.”

MDFA, too, has reporting obligations. It is a voting member of the Consumers Health Forum of Australia, which in 2005 developed a code of conduct in conjunction with Medicines Australia called Working Together. The key principles that members of the forum should follow are respect for independence, achieving and maintaining public trust, open communication, confidentiality and accountability.

MDFA’s annual report for 2012–13 mentions some of the assistance, but doesn’t acknowledge that Bayer supported research and policy projects.

The year 2015 brought another flurry of activity. In April 2015 Deloitte Access Economics produced The Economic Impact of Diabetic Macular Oedema in Australia, funded by Bayer Australia and supported by MDFA. The report again found indirect costs in the billions — this time a total cost of $2.07 billion as a result of the loss of vision associated with diabetic macular oedema, which is swelling at the back of the eye. It also found that the savings that could arise from “better access to treatment” were $350 million in 2015.

In June 2015 came a meeting of the federal government’s Drug Utilisation Sub Committee, which examines drug use where costs are high or usage is contentious. It provides advice to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee, or PBAC, which decides which drugs should be covered by the PBS.

The Sub Committee analysed the use and cost of aflibercept and ranibizumab, by then costing the PBS $330 million per year. It gave a draft report to the MDFA, the manufacturers and the professional body of eye specialists. All provided comments, though neither the draft report nor those comments are publicly available.

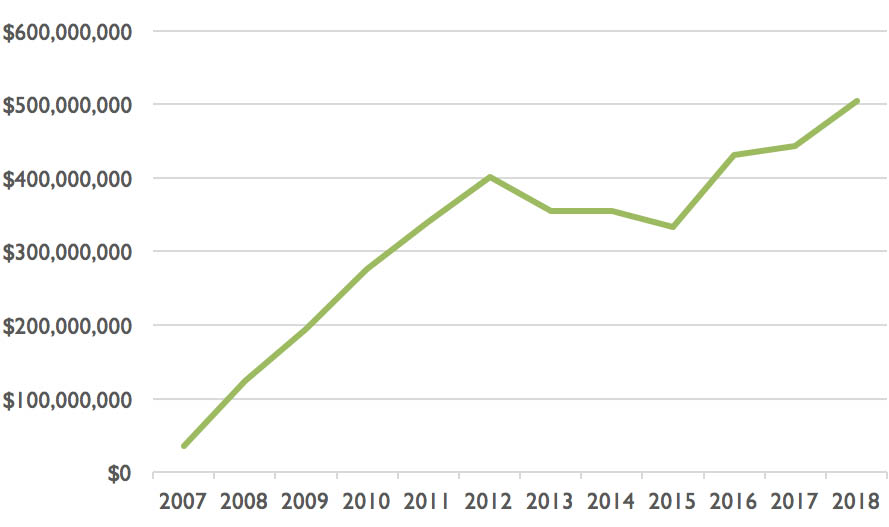

In July, October and December 2015, the PBS gradually extended the listings of ranibizumab and aflibercept to eye conditions other than macular degeneration. The annual cost to the PBS of these drugs, which had been steady for two years, jumped another $100 million to $430 million. It has continued to rise, reaching $504 million last financial year:

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme expenditure on aflibercept and ranibizumab combined

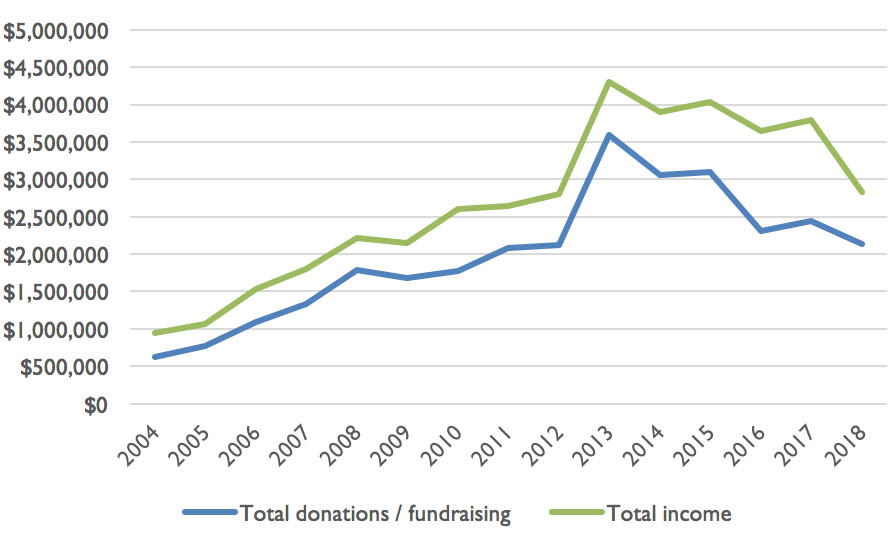

But after the peak activity of 2012 to 2015, the income of MDFA has gradually declined:

MDFA’s income: total and from donations and fundraising

Research from the Evidence, Policy and Influence Collaborative at the Charles Perkins Centre at Sydney University has shown that heavy funding by pharmaceutical companies of consumer health organisations can align with a period when that pharmaceutical company has products under review by the PBAC. In other words, when advisory bodies are making decisions that influence government expenditure on pharmaceuticals, manufacturers heavily invest in organisations that can publicly advocate for decisions in the manufacturers’ favour.

The chief executive of MDFA, Dee Hopkins, says she’s not aware of any link between funding of MDFA and the timing of PBAC reviews, but believes it wouldn’t matter. She believes that industry funding of health consumer organisations is vital, and that organisations such as MDFA are not influenced in any way at all by its source. “You can’t have the tail wagging the dog,” she says.

Hopkins believes that health consumer organisations such as hers rely on money from the industry and other corporate sources because there is not enough money from government and other potential funders. “We’ve moved the dial from a third of people having regular eye examinations to having two-thirds of people having regular eye examinations, with a decreased risk of blindness,” she says. “Without funding like ours, how else would an organisation like us exist?”

MDFA has continued to make submissions to inquiries, including to the Productivity Commission’s inquiry into the reform of human services. In that submission, MDFA argued for early diagnosis of macular disease, the immediate start of eye injections when needed, and regular ongoing use of these eye drugs as required.

This submission is typical of the seven seen by this writer — five to Productivity Commission inquiries, one to the Department of Health on private health insurance premiums, and one to the Senate standing committee on out-of-pocket costs in Australian healthcare. MDFA generally describes itself as “representing the macular disease community” and, in its standard 360-word spiel, describes its medical committees, outlines the backgrounds of its senior staff and says that it represents 53,000 people. In none of those seven submissions does it mention that it receives substantial funding from Bayer Australia and Novartis, nor does it mention their names at all. All seven submissions quote favourably from the 2011 report produced by Deloitte Access Economics, without mentioning that the report was funded by Bayer Australia.

Similarly, MDFA has a YouTube channel featuring short videos about eye health. Those videos don’t acknowledge the source of funding, either. Nor do the resources MDFA produces for GPs.

Brochures and fact sheets that promote the use of vitamin and mineral supplements don’t mention the consistent and ongoing support of Blackmores, which sells such products.

But MDFA does declare its funding in any submissions to the PBAC. As Dee Hopkins points out, the PBAC asks explicitly for such information. She says the approach of generally not naming funders is reasonable, as her organisation gets funding from sources other than pharmaceutical companies — including individual donors, government and other corporations — and it declares all its funding in its annual reports and financial statements.

For its part, Medicines Australia’s Working Together says, “The collaboration [between pharmaceutical companies and a health consumer organisation] should be open and publicly transparent. It should be declared, in forms appropriate to different audiences, while still retaining the privacy entitlements of the parties involved.”

The chief executive of the Consumers Health Forum, Leanne Wells, says that “there is potential for conflict over the portrayal of product benefits and risks, and the role that consumers and companies should play in the promotion of these. It is important that the terms of engagement are transparent, untied and disclosed.”

If the source of MDFA’s funding doesn’t influence its behaviour, then it is swimming against the tide of research in the area. For example, Health Action International has found that health consumer organisations that receive pharmaceutical industry funding believe that pharmaceutical companies have a more important role in providing information to the public than do similar organisations that don’t receive such funding.

Another study examined submissions to the US Centers for Disease Control regarding potential tightening of restrictions on opioid prescribing. Organisations that received funding from opioid manufacturers were more likely than others to oppose restrictions on prescribing. None declared they were funded by manufacturers of opioids.

And there is a wealth of research showing that doctors who receive pharmaceutical company funding behave differently from doctors who don’t. In one US study, the more payments doctors received from the pharmaceutical industry the more likely they were to prescribe industry products. Yet most surveys show that doctors who take funding from pharmaceutical companies believe it has no influence.

Dr Barbara Mintzes, a member of the Evidence, Policy and Influence Collaborative, says there are concerns about what consumer organisations don’t say as well as what they do say. For example, in the early 2000s it was discovered that the anti-inflammatory drug Vioxx could lead to heart attack and death. The manufacturers, Merck, withdrew the drug, and it later emerged that it had hidden its knowledge of the risks. Yet during this time, in Mintzes’s native Canada, the only reaction of the rheumatology consumer group was to congratulate Merck for acting voluntarily. “There was no advocacy for their members,” she says.

As Australian researchers Ray Moynihan and Lisa Bero wrote recently in JAMA Internal Medicine:

Patient advocacy groups play an increasingly powerful role in health care, sponsoring research, producing or promoting guidelines, driving media coverage, influencing regulatory decisions, promoting certain interventions, and shaping the way we think about disease. Just as the industry funding of clinical trials has been associated with more favourable findings, patient groups also face risks of bias when accepting money from companies seeking to expand markets for their new tests and treatments.

Mintzes puts it this way: “If Choice magazine was providing information to the public on washing machines, and they were funded by one manufacturer of washing machines, their service would be rubbished. But consumer groups who get their funding from manufacturers, well…”

When asked about the research, MDFA’s Dee Hopkins initially says, “I can’t talk to that.” But later she says she was disappointed in the research, and didn’t believe it took into account the level of maturity shown by Australian consumer health organisations.

The sums involved are mind-boggling. Bayer Australia and Novartis have so far received close to $2 billion in government subsidies for the two eye drugs that are listed on the PBS. And the support of MDFA, backed by funding from Bayer Australia and Novartis, helped those drugs get listed. So did the efforts of Deloitte Access Economics in reports funded by Bayer Australia and Novartis.

And one of the more unusual aspects of all this is that some of the money the companies spend to support MDFA, knowing MDFA’s voice will support them, comes from public funds. After all, MDFA is a registered charity, and industry contributions to it are tax-deductible. So we all play our part when drug companies fund community groups, whether we know it or not. •

This article is co-published with the health policy website Croakey, where a more detailed list of Bayer’s and Novartis’s sponsorships of MDFA also appears.

Declaration of interest: Mark Ragg edited several public summary documents for the Drug Utilisation Sub Committee of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee in about 2012–13. He did not work on either aflibercept or ranibizumab, and has seen no confidential information on these products, nor on any organisation mentioned in this article.