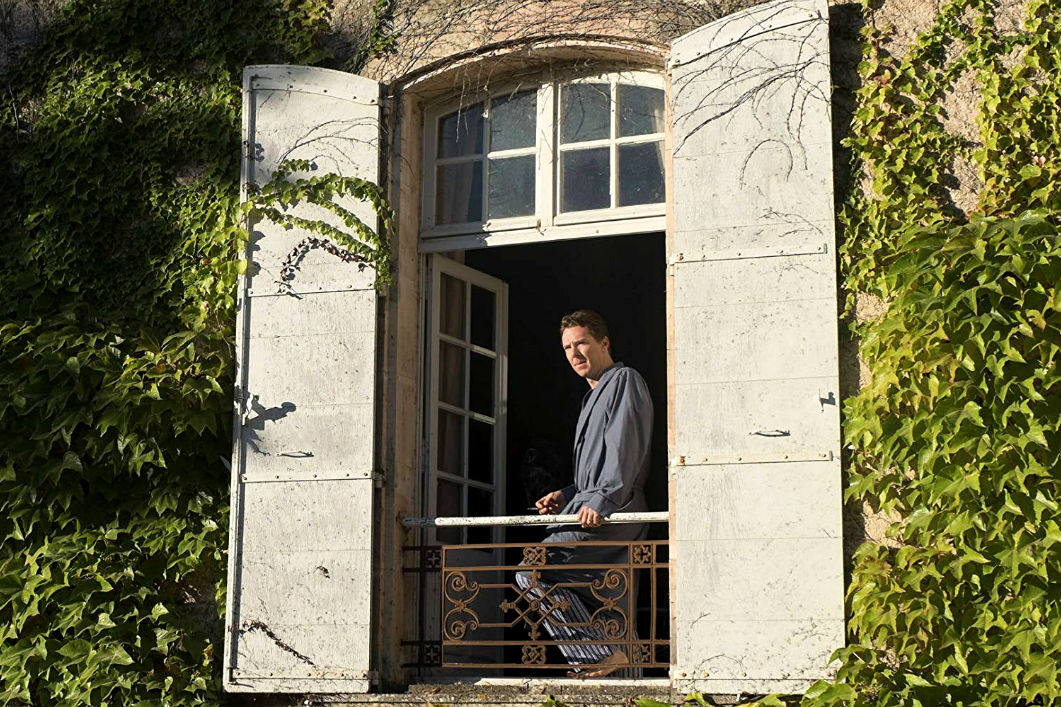

Episode three of the Showtime series Patrick Melrose (BBC First) is set in a Georgian mansion. A high-society dinner party is taking place with Princess Margaret as guest of honour, and Patrick, in the throes of withdrawal from alcoholism and heroin addiction, is bidden to the feast. Forced out of his curtained bolthole by a family friend, the appropriately named Nicholas Pratt, Patrick manages to get himself together and front up, impeccably groomed, to the kind of ritual ordeal only British aristocrats know how to devise.

The mansion’s pillared facade and neoclassical architecture express eighteenth-century values of order, harmony and symmetry. As waiters set the table with geometric precision, every polished plate and gilt-edged glass positioned with the aid of metal rulers, the guests assemble in designer gowns and begin to circle each other, negotiating their place in the pecking order.

In fact, pecking is what it seems to be all about, and some beaks are sharper than others. For those with a little wit, artfully turned phrases can draw blood. Princess Margaret, played by Harriet Walter with an austere glamour more reminiscent of the Duchess of Windsor, has no wit at all, but attracts a flotilla of sycophants who laugh delightedly at her idiotic stories.

Before long, in defiance of the formal aesthetics of the surroundings, primordial human nature takes over. Quarrels break out, insults fly. In a scene that replicates a memory from Patrick’s childhood, the hostess’s little daughter sits on the stairs alone, hoping for some encounter with the adult world, and then is drawn into it only as the target of withering cruelty.

The autobiographical novels by Edward St Aubyn on which the series is based are all about cruelty to children. St Aubyn himself was sexually abused by his father before he was seven years old and blames his mother for deliberately turning a blind eye and effectively making him a toy in their sadomasochistic relationship. As an adult, he resorted to drugs and alcohol to mask the recurrent anguish, and exercised his gifts as a writer to render the flashback experiences as a kind of literary chamber music.

In the novels, his distressed alter ego Patrick is a virtuoso of performative bitterness, moving through the phases of adult life with a crippling disability. Determined not to pass on the cruelty like a hereditary curse, he puts everything he has into being a good father to his own sons, but dealing with the deaths of his parents is too much of a reckoning, and he relapses.

The five episodes of the television adaptation themselves form a symmetrical design. The first centres on the death of Patrick’s father and the last on that of his mother. Childhood is the focus of the second and fourth — his own childhood story, then that of his sons, Robert and Thomas. The central episode, a cross between Brideshead Revisited and the Mad Hatter’s tea party, creates the setting in which he manages for the first time to speak of the unspeakable. Standing on the terrace outside the grand house, Patrick makes a bid to come out with the truth to his friend Johnny, also a recovering alcoholic. “I told you there was something I’d never said out loud and never would…”

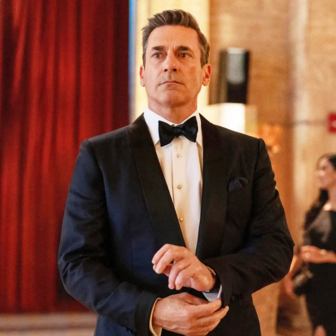

It is easy to see why the five episodes were five years in the planning, and why it was only when Benedict Cumberbatch declared that this role, along with Hamlet, was top of his bucket list that the wheels were in motion. As he struggles with the bludgeoning impact of four words — “My father raped me” — Cumberbatch’s face speaks more lines than there are in a Hamlet soliloquy. Cumberbatch is to acting as St Aubyn is to literary prose — both of them push human communication to places that might never have seemed reachable. Evidently there was a rapport between the two of them, so that there was an element of collaboration in realising the character on screen. St Aubyn is also credited as a co-writer of the series, together with David Nicholls, who has written the screenplays for a number of classic English novels, including Far from the Madding Crowd (2015), Great Expectations (2012) and Tess of the D’Urbervilles (2008).

With their evocation of the dysfunctional world of British aristocracy, the Melrose novels were crying out for dramatisation. They suffer at times from verbal over-reach, as when Patrick imagines himself as “a solitary observer training his binoculars on some rare species of insight usually obscured by the mass of obligations that swayed before him like a swarm of twittering starlings.” The presence of a good actor is a wonderful substitute for this kind of tortuous psychologising.

Cumberbatch is supported by an exceptional cast. Hugo Weaving as Patrick’s sadistic father David has an impeccable sense of the voice and manner of a man literally perverted by the conventions of social class. It is as if the exaggerated persona serves as a crucible for the worst human impulses. Jennifer Jason Leigh as his wife Eleanor is at once fragile and pig-headed, playing the contradictions with quicksilver intelligence. Bridget Watson Scott, an airheaded social climber who makes a disastrous marriage into the highest echelons, is played by Holliday Grainger with the finest subtlety.

There is, though, one serious mistake in the casting. Sebastian Maltz as the child Patrick is a very engaging young actor, but he and Cumberbatch are so physiologically unlike that it is almost impossible to see them as the same person. Maltz has Mediterranean colouring: olive skin, black hair and dark eyes. Cumberbatch, with his blue eyes, brown hair and fair skin, could not, even with the assistance of an advanced make-up artist, look Mediterranean. The dissociation matters. The dramatic tension of every episode depends upon the weave of fathers and sons, of adult and child consciousnesses. ●