It was scarcely surprising that the release last week of the Productivity Commission’s five-yearly review of Australia’s productivity performance had very little impact. Competing with AUKUS and a sensational defamation trial, it lacked the kind of bold policy proposals that would make for big headlines. The central point, aired in advance, was an obvious one: without productivity growth we can’t improve living standards significantly.

The report included sensible discussion of a wide range of options for promoting productivity, none of which were likely to provoke violent controversy. But, like Sherlock Holmes’s dog that didn’t bark, the absence of controversy is notable and revealing.

The trajectory of the Productivity Commission is a microcosm of the history of neoliberalism (often described in Australia as “economic rationalism” and “microeconomic reform”). During the fifty years since the early 1970s, neoliberalism has gone from being an economic policy revolution (or counter-revolution) to being a dominant ideology, before finally fading to near irrelevance.

The Productivity Commission dates back to the beginning of that period, in 1973, when it replaced the old Tariff Board. In those early days it was called the Industries Assistance Commission, or IAC, and it was part of the first bout of microeconomic reform in Australia.

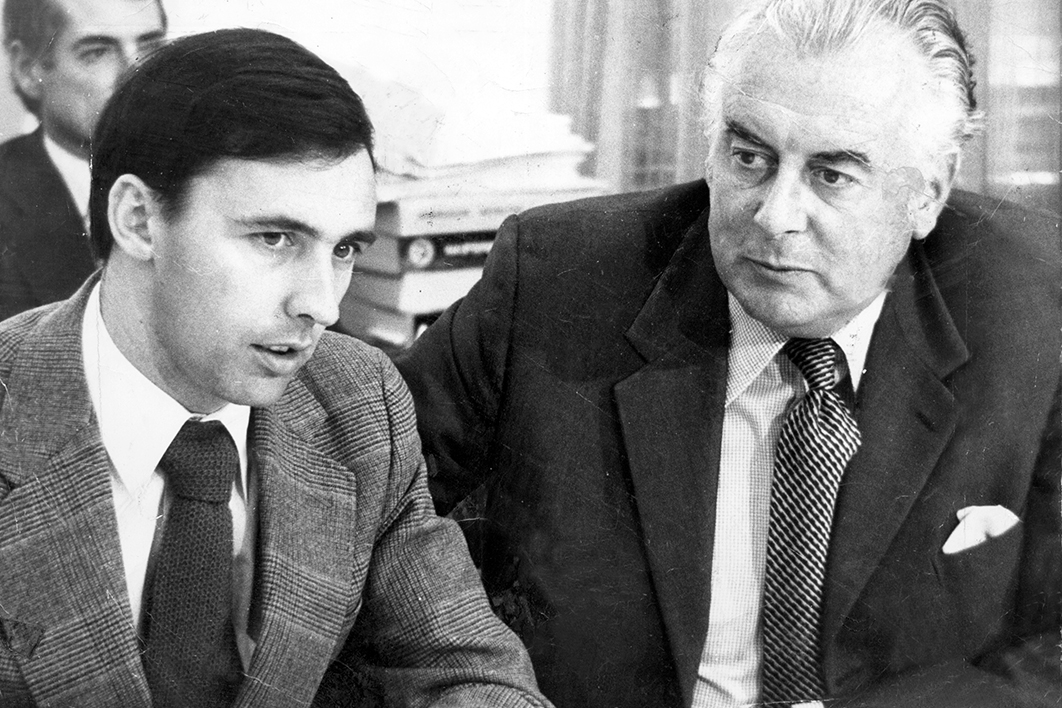

Prime minister Gough Whitlam had recently taken power, and his government — despite its big spending program — was the first to promote economic rationalism. It cut tariffs across the board by 25 per cent and abolished the superphosphate fertiliser bounty paid to farmers, repudiating the policy of “protection all round” promoted most strongly by Country Party leader John “Black Jack” McEwen.

“Protection all round” combined import tariffs, which raised costs for farmers, with subsidies (like the superphosphate bounty), which lowered them. Struck by the difficulty of working out the net effect of these policies, one of Australia’s great economists, Max Corden, developed the concept of “effective protection.”

Decisions to cut industry assistance were unpopular, to put it mildly, in the sectors directly affected. The IAC’s job was to analyse the impact of such policies on the economy as a whole. It took on a task that had previously been split between the Tariff Board, which advised on protection for manufacturing, and the Department of Primary Industry, which dealt with assistance to agriculture.

While the Tariff Board had moved towards a more critical perspective on protection under its final chairman, Alf Rattigan, the new IAC (also chaired by Rattigan) was unabashedly ideological. Its primary objective was to “improve the efficiency with which the community’s productive resources are used.” While ordinary Australians might have understood this to refer to the efficiency of production, or “productivity,” the IAC interpreted it in the technical sense dominant in economics, which implied the need to remove all “distortions,” such as tariffs and subsidies. The paradox of an IAC rigidly opposed to assisting industries eventually led to a shortening of its name to the Industries Commission.

Disputes over tariffs dominated the work of the IAC and the IC over the 1970s and 1980s. The cause of free trade lost ground under the Fraser government before triumphing under the Hawke–Keating government and its successors. Today there is virtually nothing left of “protection all round,” or of the manufacturing sector it protected. What remains of Australian manufacturing is dominated by simple products like meat, bread and wine, along with limited processing of minerals and a handful of niche producers of high-tech equipment.

As the importance of manufacturing declined, the scope of microeconomic reform expanded. National competition policy, privatisation and public–private partnerships were all on the agenda. From a relatively limited program of “getting prices right” in the 1970s, the advocates of neoliberalism had shifted their focus to comprehensively reversing the growth of government during the twentieth century.

The glory days of the Productivity Commission were the 1990s. (The name was adopted in 1996 when the IC swallowed its main institutional rivals, the Economic Planning Advisory Council and the Bureau of Industry Economics.) Using measures newly developed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the PC announced that Australia was experiencing a “productivity miracle.” More precisely, this marvellous performance was not so much miraculous as “the ‘predictable’ outcome of policy reforms designed to raise Australia’s productivity performance.”

By the time the PC released an account of its first thirty years in 2003, the glow of the productivity miracle was beginning to fade. But there were still grounds for confidence that the program of reform would continue, delivering improved living standards for all Australians.

As it turned out, the process of microeconomic reform was pretty much over. National competition policy had run its course. The tide was beginning to turn against privatisation. The one major attempt at continued reform, John Howard’s WorkChoices, was a political disaster largely reversed under the Rudd–Gillard government.

Moreover, the productivity miracle fizzled out completely. Dispute remains over whether it was a statistical illusion or an unsustainable blip. But, as the latest five-year report shows, the reforms of the late twentieth century didn’t deliver a boost in productivity. Over the period since 1990 (which includes the “miracle” years), annual labour productivity growth has averaged 1.6 per cent, lower than the 2.4 per cent recorded in the 1960s and 1970s.

There are many reasons for this decline, but the most important is the transformation of the economy from one based on producing, transporting and distributing physical goods to one based on human services and information. To the extent that they were ever relevant, the policy prescriptions of twentieth-century neoliberalism have nothing to offer here. On the other hand, we have yet to see the emergence of a coherent alternative.

To its credit, the PC has responded by focusing on more relevant policy issues. The central themes of last week’s report are improving education and managing energy transition. The recommendations are sensible, with little if any ideological content.

Privatisation, once the signature policy of neoliberalism, gets only a single, negative mention, in a discussion of the impact of the privatisation of building surveyors in the 1990s. It seems likely that privatisation’s last gasp, the sale of state land titles offices, will be similarly disastrous.

The “good fight” against tariffs gets a brief run, with the argument that tariffs are now so low that compliance costs outweigh any revenue benefits. The PC’s view that they should be reduced to zero is hard to disagree with.

As has been true throughout its fifty-year existence, the Productivity Commission has produced another piece of well-written and professional analysis. But whether it is worth extending the life of a body so thoroughly tied to the era of neoliberalism is an open question. •