WHAT is it about the Greens that Labor so dislikes? Prior to the Tasmanian elections Labor premier David Bartlett assured voters he would not be doing a deal with them under any circumstances. In the event, Labor formed a minority government with two Green cabinet ministers. Had it not been for the Greens and the movements they represent, it’s likely that in Tasmania alone the Gordon below Franklin would have been dammed and the Gunns pulp mill development would have gone unchallenged. That aside, on so many issues – climate change, industrial relations, welfare, foreign relations and economic matters, for example – the Greens are closer to Labor than Labor is to the Coalition.

Federally, Green preferences boost federal Labor’s two-party preferred vote at every election. In 2007 Labor’s primary vote, at 43.3 per cent, was only 1.3 per cent higher than the Coalition’s. But with Green preferences the two-party-preferred outcome – 52.7 per cent for Labor and 47.3 per cent for the Coalition – put Labor into office. Despite this, the Rudd government goes first to the Coalition to negotiate Senate deals.

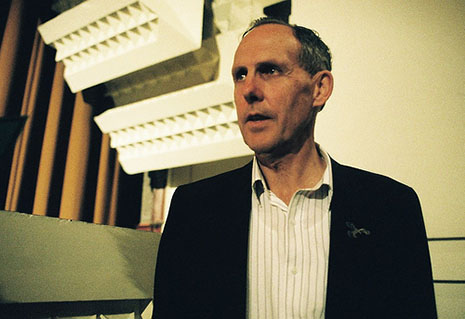

Bob Brown is not everyone’s cup of tea. But no one can doubt his achievement in boosting the Greens to the third political force in Australian politics. Mr Rudd is not impressed; despite a number of polite requests since last July, he won’t even meet with Senator Brown.

Penny Wong, minister in charge of the steering the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme, or CPRS, through the Senate, was happy to negotiate amendments with the Liberals’ Ian Macfarlane last year. Although she is courteous enough to meet with the deputy Greens leader, Senator Christine Milne, she has refused to enter into serious negotiations about changes to the scheme to deal with Green concerns. The Greens believe Wong’s behaviour is understandable, given her background: before entering parliament she was a union official in the forestry division of the CFMEU, whose members stand shoulder to shoulder with the loggers and pulpers against the Greens. Wong later became a staffer to Kim Yeadon, then Minister for Land and Water in the NSW government and definitely not a friend of the Greens.

Now, Labor has broken the most important promise of all – early action on climate change. The government has shelved the CPRS legislation until some time after the next election later this year. Yet only last week the prime minister told the Sydney Morning Herald that “on the question of climate change policy, our policy hasn’t changed. We maintain our position that this [the CPRS] is part of the most efficient and the most effective means by which we can reduce greenhouse gas emissions with least cost to the economy.”

Brave words, but the prime minister has not held a double dissolution election, the logical way to break the Senate deadlock. In the meantime, support for his position on climate change has eroded. A new Climate Institute poll shows that the percentage of voters trusting Mr Rudd most on climate change fell from 46 per cent last year to 36 per cent in April. Those believing there was no difference on climate change between Mr Rudd and Mr Abbott rose from 37 per cent to 40 per cent.

The Greens will hold the balance of power in the Senate after the next election and Rudd may have to rely on them to pass a climate bill. After another election defeat, of course, there could be a change of heart among the Liberals. Tony Abbott will be dumped and the next leader (perhaps Joe Hockey or, if he reverses his decision to retire, Malcolm Turnbull) would accept the government mandate for the legislation. (All this presumes Labor would win the election, which is highly likely, but not certain.)

But there is a broader problem with Labor’s approach to climate. Although some may say that it is better than nothing, the CPRS legislation is badly flawed. Its unconditional target for emissions reductions – 5 per cent on 1990 levels by 2020 – is way too low given that the science calls for a 40 per cent cut. The Greens say the bill should stipulate at least a 25 per cent target, and they prefer Ross Garnaut’s interim approach in the absence of a decent emissions trading scheme. Professor Garnaut suggested setting a carbon price beginning at $20 a tonne (in 2000 dollars) rising to $24.50 in 2011 and $26 after that. Polluters would be taxed on these levels, and Garnaut suggested compensation to householders could flow from revenue collected. This would also mean a quite light tax for a low-polluting industry such as car manufacturing but a heavier tax for high polluters such as coal-fired power-generating plants and oil refineries.

In the past week even more criticism has been heaped on the CPRS for its generous handouts to polluters by way of compensation. The Grattan Institute’s new study shows that the compensation handouts to “trade exposed industries” would be “a $20 billion waste of money.” It assembled evidence that only two industries – cement and steel – would deserve assistance. Alumina, liquefied natural gas and coalmining would remain internationally competitive without assistance; granting them free permits would amount to supporting industries that are likely to leave Australia anyway.

The Grattan Institute’s energy research fellow, Tristan Edis, estimates free permits cost about $59,000 per employee on average, soaring to $161,100 in the aluminium industry and $103,300 in liquefied natural gas. The institute’s CEO, John Daley, explains that most of the proposed compensation would be wasted because most of the industries are unlikely to move offshore and will remain very profitable with or without a carbon price. Given that the institute’s founders include BHP Billiton and the federal government, this is telling criticism indeed. Mr Rudd’s authority and credibility in the parliament and the Labor caucus have been greatly diminished. •