A few years ago one of Australia’s more exclusive schools was compiling profiles of its most notable alumni for an anniversary book. It asked me whether I’d write a few chapters and showed me a list of businessmen, sportsmen, scientists and even prime ministers to choose from. They were all interesting people, but to my mind there was only one criterion. Whom did I want to meet?

There he was, James Oswald Fairfax AC, the one-time heir to a media empire and among Australia’s greatest philanthropists. This was the person who usurped his father to take control of the country’s oldest broadsheet newspapers and who, in turn, was forced out by his half-brother, partly in revenge for the way their father was treated. It’s one of the epic sagas of Australian media history, involving a supposedly scheming wife who raised a son to resent his cousins and half-brother. It reads like the plot for an operatic tragedy, and the events shaped much of Australia’s modern media landscape.

No question; I would profile him.

Before long I was on the phone to his home at Bowral, in country New South Wales. A kindly assistant answered and transferred the call, and a soft voice with a rather exaggerated plumminess came on the line.

“How lovely of you to ring,” said James Fairfax. He had been tipped off by the school and was already committed to an interview. The question was how it was to be done.

“Well, perhaps I could ask you some questions by phone,” I suggested.

“Yes, we could do that,” he replied, unconvinced. “But I would rather like to do this in person… Where are you living nowadays?”

It was as if we were old friends who had lost touch for a year or two.

“I’m in Melbourne,” I replied, assuming that would settle the matter and we could get on with a phone interview.

“Oh, well, I’ll send the car,” he said, in a tone of absolute assurance, like he had solved a simple problem. After all, what was all the fuss about?

“Ah, thank you,” I offered. “But it’s a long way.”

“I would rather like to talk to you in person,” he repeated. “You could come for lunch. You could stay the night if you like.”

Clearly he had something important to say. Either that or he was very keen for someone to chat to. So I asked to be put back to his assistant, who I think sighed just a little as I explained Mr Fairfax’s wishes. Did he do this for everyone, I wondered.

And so – I hereby declare – James Fairfax flew me to Sydney, and there his chauffeur was waiting to drive the one hundred kilometres to Retford Park, his grand, pink Italianate mansion on the edge of the country town.

The grounds had that imposing aspect you hope for when you approach a country estate along a winding driveway through manicured gardens. Only the lake was a little disappointing, more like a stagnant pond than a river of gold. Fairfax later gave the entire $20 million estate to the National Trust, with the adjoining land sold off to ensure the property’s upkeep.

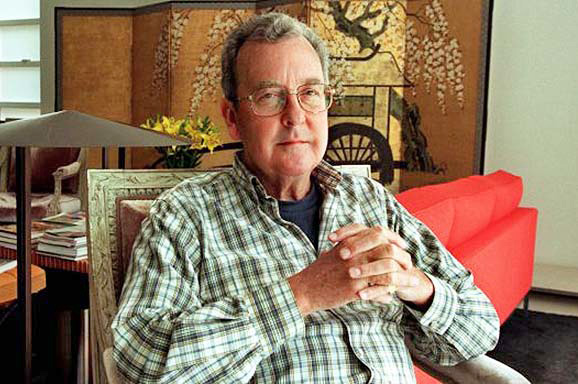

The chauffeur, who spoke of his boss with reverence, called ahead to signal the incoming guest, and so when we arrived he was standing on the verandah with his two perfectly groomed dogs. He was a little stooped in his comfortable slacks and casual shirt. We swapped pleasantries and he beckoned me onto the verandah, where we were served champagne and ate wafers and a selection of pate and cheeses from a tray.

Now, you should probably know that the school in question was Geelong Grammar, which was a sandpit for a remarkable number of future media moguls. James’s father Sir Warwick went there, as did his cousin John B. Fairfax. Kerry Packer was a student, along with members of the Holmes à Court family and Ranald Macdonald, who went on to run the Age. On one of his first days as a boarder at the junior school, James Fairfax was told that “the commo” was waiting outside to see him. So out he went to find yet another future mogul, young Rupert Murdoch, standing on the lawn.

Murdoch was a couple of years ahead of Fairfax, and was known at the time for his left-wing views. It was the first time the heirs to Australia’s two major newspaper companies had met. They would later become intense rivals, but at the time Fairfax appreciated the gesture of welcome. “It was nice of him to do that,” he recalled.

“I am determined to be positive about Geelong Grammar,” James Fairfax wrote in his memoir, My Regards to Broadway. I asked him about that intriguing line and, as a cockatoo screeched in the trees and he poured us another glass, he explained how he had been the subject of “ragging” during his school days. Nowadays it’s better known as bullying. “They took it out on me from time to time. It was mainly verbal but they made things unpleasant.”

“In senior school,” he added, “they had it down to a slightly fine art. I might have appeared reserved. They thought I didn’t like them or want to be close to them. I didn’t think I was all that different to anyone else.”

But it wasn’t all bad. His headmaster deeply influenced him, and one particular art teacher, a postwar eastern European refugee, changed the course of his life by exposing him to 1920s German art. “He taught me to appreciate modern art going into abstract art,” Fairfax said.

By now we had moved inside to the dining room, where lunch was to be served. The dogs followed and lay on the floor. As he poured red wine, we admired a John Olsen painting on the wall and he explained he had “no idea” how many pictures he had donated to galleries across the nation. “Quite a few I’d imagine,” he said.

At least a couple of red wines later, the conversation made its way to the failed takeover bid by James Fairfax’s younger half-brother, Warwick. It’s the topic that’s defined the Fairfax company and family since 1987.

Young Warwick is the son of James’s late father, Sir Warwick, and Sir Warwick’s third wife, Lady Mary. Instead of waiting for his inheritance, Young Warwick launched a reckless, debt-fuelled takeover bid, advised by the discredited Western Australian businessman Laurie Connell. For James and his two cousins, Sir Vincent and John B. Fairfax, this was a complete shock. The bid coincided with the stockmarket crash and the family eventually lost control of the business. It ended James’s career at the company, where he had been a director since the 1950s and chairman since 1977. He sold his shareholding for an estimated $168 million.

So, in the twilight of his life, how did James Fairfax reflect on both the destruction of the dynasty and the people he considered responsible, namely his half-brother Young Warwick and stepmother Lady Mary?

On one level, he seemed quite sanguine and forgiving: “It’s all in the past now. I really stopped thinking about it years ago, not that it kept me awake at night, but what’s done is done and cannot be undone, can it?” But as the lunch meandered on, other feelings emerged, suggesting that those events still hurt a quarter of a century later.

He described the day Young Warwick visited his Darling Point home after lodging his bid with the Sydney Stock Exchange. “He came to see me at Lindsay Avenue and he sat there motionless and [almost] speechless for about forty-five minutes, well it seemed like forty-five minutes, and then he went to cousins John and Vincent and we all fairly briefly rang each other and he pretty well said the same thing to all of us. Vincent was absolutely broken up, poor old boy. And, well, John and I felt the same thing about it and there was nothing to be done because the offer, whatever you do, was put into the Stock Exchange on the Monday morning and then the phones ran hot.”

He went on: “I thought to myself, how ironic. My father used to refer to Young Warwick as ‘the hope of the side’ and, one thing, Warwick said he would not have done it if his father was still alive. Well, that was fairly obvious, one would have to say, and I think it was several years before I really spoke to him again.”

Did he ever wonder, I asked, what might have been for the Fairfax company if Young Warwick hadn’t made his bid?

“I think the family would still be owning it and controlling it. What he did was bugger himself and nearly bugger the company. To what degree his mother was either behind it or knew anything about it, well, your guess is as good as mine. I personally think he would have certainly spoken to her about it because anything to get me out and John out would have been an aim in itself.”

An aim of his or an aim of Mary’s?

“An aim of Mary’s. She could influence him any way she wanted.”

What would Sir Warwick have thought about it?

“It would have depended a little on how successful it had been or wasn’t, and as it was a miserable failure he would have… if he had been involved in it he would have accepted his own responsibility, which was the last thing Mary did of course. But he [Sir Warwick] was honest and he would have accepted, I think, that he had made a few misjudgements. I think he would have been absolutely horrified.”

Does Warwick now reflect on it and talk about it?

“Oh well, he’ll talk about it up to a point and do his best to get out of any awkward questions, but at my age I frankly don’t care anymore.”

And have you and Warwick reconciled?

“I never see him. It’s that simple. We’re polite to each other when we do. There’s no point, when everything is over, in bearing old grudges. Well, what’s the point of not speaking to him? Absolutely none. Not that he has ever apologised in a sense, but still, what’s over is over, and we’re never going to be buddies. But I say hello to him. I don’t see him particularly. If he rang me up, I’d answer the telephone.”

Would an apology for the disastrous bid be appropriate?

“Well, again, if his mother let him, which she never would, his own inclination probably would be. But I’m not going to sit here for five years waiting for an apology because I’m not going to get one.”

After a short pause, and with perfect elocution, he continued, “And I don’t give a fuck, quite frankly.” The distinct articulation of give-a-fuck was a little shocking. He was clearly done with this topic. “I’m not going to let it worry me and I’ve long ceased to let it worry me,” he concluded.

On that day in Bowral I saw one of the last vestiges of the power and privilege associated with Australia’s establishment media. James Fairfax was one of the last great patrician proprietors. While he was unashamedly conservative in outlook, he also valued and upheld the traditions of free speech and pluralism. He respected the craft of journalism and, as chairman of the family company, generally allowed it to prosper.

But I suspect that he and his cousins were saved from the inevitable. I suspect they would have been just as ill-prepared for the digital revolution that was about to sweep across the business. Instead, James Fairfax excelled at a life of splendid retirement, surrounded by the trappings of the wealth that he became so very good at giving away.

To end the interview, I thanked him for his hospitality and asked whether there was anything he wanted to add. My recording of that conversation cuts out with these words: “Great pleasure. Now, I tell you what, if you give me a tiny bit more wine I’ll endeavour to think of something…” Sound of wine being poured. “Thank you, that’s fine. Now, where were we…?” •