Framing the Islands: Power and Diplomatic Agency in Pacific Regionalism

By Greg Fry | ANU Press | $55 or free download | 399 pages

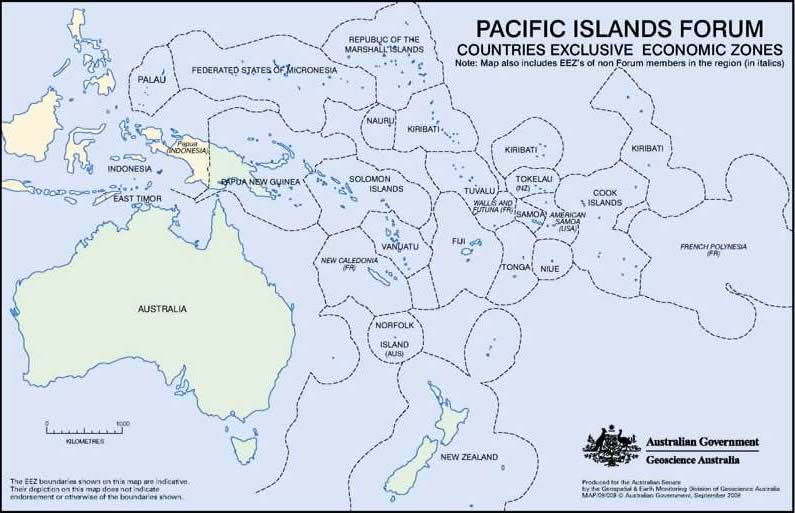

The map of Pacific island maritime boundaries is also the image of a paradigm shift.

This fundamental change in the understandings and imaginings of the islands was delivered by the UN’s creation of 200-mile exclusive economic zones. Once the 1982 law of the sea convention had done its legal magic, the South Pacific transformed from islands in a far sea to a “sea of islands.” The old map of tiny specks in a vast expanse of blue gave way to a group of big nations in a connected Oceania. Truly, new map, new world.

Map: Geoscience Australia

That’s paradigm-shifting with diplomatic and economic punch, not least in transforming the way islanders understand themselves and their place in the world.

These thoughts on the sea of islands come from Epeli Hau‘ofa, a wonderful islander who grew up in Papua New Guinea, Tonga and Fiji. He attacked the European framing of the islands, which was as much about mentality as maps:

Nineteenth-century imperialism erected boundaries that led to the contraction of Oceania, transforming a once boundless world into the Pacific Island states and territories that we know today. People were confined to their tiny spaces, isolated from each other. No longer could they travel freely to do what they had done for centuries. They were cut off from their relatives abroad, from their far-flung sources of wealth and cultural enrichment. This is the historical basis of the view that our countries are small, poor, and isolated.

Epeli embodied the phrase “scholar and gentleman” and his work lives on. The core expression of today’s regionalism, the Blue Pacific, is built on Epeli’s “new Oceania” and the social networks he called “the ocean in us.”

All this is by way of an introduction for Greg Fry’s major work of scholarship, forty-five years in the making, on power and diplomatic agency in Pacific regionalism. Framing the Islands started germinating in 1975, with Fry’s fieldwork for an Australian National University thesis on regionalism in the early postcolonial period.

Fry’s fine history will help you understand much about where the islands have been and where they could go. While you’re downloading it free from ANU Press, get a copy of its companion volume, The New Pacific Diplomacy, a book Fry co-edited in 2015.

The new book was launched in Canberra by one of the leaders of the South Pacific, the formidable and admirable Dame Meg Taylor, secretary-general of the Pacific Islands Forum. She lauded its celebration of often-overlooked Pacific action in regional and global affairs, and praised it as a “clear and robust” guide to “the contested past, present and future of Pacific regionalism.”

Taylor says Framing the Islands shows the “political savvy and adaptability” of Pacific regionalism through “the constitution of a strategic political arena for the negotiation of globalisation,” “the provision of regional governance,” “the building of a regional political community” and “the operation of a regional diplomatic bloc.”

Fry writes of the puzzle of Pacific regionalism, ranging from security, conflict resolution and fishing to shipping, trade, nuclear issues and the environment:

The Pacific is invoked sometimes as a regional cultural identity; sometimes as a political community with its own values, norms and practices; sometimes as a collective diplomatic agent; and sometimes as a site of political struggle. Situated between the global arena and local states and societies, it also appears as a mediator of global processes — sometimes as an agent for outside forces and sometimes as a “shield” for local practices.

Under the Old Mates Act, I declare I’ve been learning from Greg for decades; he was my teacher twenty-five years ago when I’d flit from the parliamentary press gallery to the ANU to study international relations.

Greg, too, is a scholar and a gentleman, with the broad grin of a happy warrior. He has greatly influenced my thinking on the islands, not least because we often disagree. We’re as one on the importance of the South Pacific; beyond that begins an argument about meaning and interpretation — and, especially, Australia’s role.

Greg is scornful of Oz hegemonic approaches; I tend to ask which big power you’d prefer. If not Oz, then…?

His book tracks the effort by Fiji’s Frank Bainimarama to expel Australia from regional membership. (My description is that Fiji was the revisionist power fighting Australia as the status quo power.) He reports how island leaders rejected Fiji’s expulsion campaign, instead embracing Australia (and New Zealand) as of and in the region. He doesn’t dwell on the logic that Bainimarama just last year created a new vuvale partnership with Australia, both for the benefits on offer and for the deeply pragmatic reason that we’re a known entity with a long record.

The Oz history in the South Pacific is both asset and handicap; they know and remember us much more than we know and remember the islands.

Fry’s summation of Australian standing is acid but accurate. Australia and New Zealand, he writes, are not emotionally part of the Pacific regional identity (a charge that won’t cause heartburn in Canberra but will provoke a lot of Kiwi pushback). Even so, Fry concludes, the Oz–Kiwi claim to be part of the Pacific “family” is accepted:

In many ways, the Pacific island states retain a surprisingly generous stance towards Canberra and Wellington. They still describe them as “big brothers” and see them as part of the Pacific “family,” even if they currently feel they are acting as “bad brothers” and not conducting dialogue within the family in a respectful way. A major contingent factor for the future of Pacific regionalism is therefore the degree to which Australia can overcome the preconceptions that have always flowed from its tendency to see this region as its “own patch.”

The “our patch” line points to Australia’s oldest instinct in the South Pacific — strategic denial. And discussion of the future of regionalism faces the fundamental issue of how much integration the islands want or need as they create a collective Pacific identity.

Strategic denial — the effort to exclude other major powers from the region — is Australia’s deepest instinct in the South Pacific. With complete dominance impossible, the instinct is beset by a faint, constant ache. Throughout the twentieth century, that ache was directed variously at France, Germany and Russia. It became a fevered nightmare during the war with Japan.

Today, Australia sees its interests and influence in the South Pacific directly challenged by China. The challenge rouses the same impulse that fostered Federation in 1901 and was expressed in the Commonwealth of Australia’s founding document. Our Constitution has one clause stating the parliament’s power over external affairs, while the next clause specifically expresses the denial impulse, identifying authority over the “relations of the Commonwealth with the islands of the Pacific.”

As Greg Fry observes, the hegemonic agenda has a long history. He quotes a nineteenth-century observation from Otto von Bismarck about the “Australasian Monroe doctrine,” referring to the policy that opposed European colonialism in the Americas.

The same sphere-of-influence intent prevails today, Fry writes, as Canberra asserts its leadership and management role: “Australia’s preferred regional order is one in which it is the leading external security partner to Pacific island states and the undue influence of other metropolitan powers, particularly China, has been denied.”

Australia and New Zealand, he notes, have had “enormous influence on Pacific regionalism — on its finances, agenda, policy directions and institutional development.” Yet, Australia is the frustrated, edgy hegemon; the problem for Oz leadership is generating enough island followership. As Fry puts it, “Power as capacity has not easily translated into power as legitimate influence.” So Australia’s influence in the islands is at times limited, and may be declining.

Australia’s habits and interests bump up against “the ‘new’ Pacific diplomacy,” Fry says, as island leaders project an assertive regional identity and seek to act as “a diplomatic bloc promoting a Pacific voice in global arenas.”

Climate change has given Pacific diplomacy urgency and unity, raising doubts about Australia’s regional membership, much less leadership:

In many ways, climate change has become the Pacific’s nuclear testing issue of the twenty-first century; it has brought an urgency and emotional commitment to regional collaboration. Where the Pacific states might in the past have tolerated some frustration with the domination of the regional agenda by Canberra and Wellington to pursue the war on terror or to promote a regional neoliberal economic order, this tolerance reached its limit in relation to the climate change issue.

The islands have acted to “securitise the climate emergency” by expanding the concept of security, declaring climate change “the single greatest threat to the livelihoods, security and wellbeing of the peoples of the Pacific.”

Fry says the islands have resisted what he calls “coercive” European-style integration. Since the end of the cold war, he writes, Australia has been the chief exponent of coercive integration, using the Pacific Islands Forum to push for regional norms to govern island development and governance.

A notable element of Australia’s 2017 foreign policy white paper was its adoption of integration as a key objective. “This new approach,” it said, “recognises that more ambitious engagement by Australia, including helping to integrate Pacific countries into the Australian and New Zealand economies and our security institutions, is essential to the long-term stability and economic prospects of the Pacific.”

Integration shows Australia’s problem of winning followership. Indeed, integration has become the i-word — the Oz policy that can’t be named — though it got an embrace from Dame Meg at the launch:

Contrary to Greg, I don’t think we should be dismissive of opportunities for regional integration in the Pacific, whether they be economic, political or based on something else. I would argue that the Rarotonga Treaty can be considered as an example of regional integration through which national sovereignty has been transcended [by] delineating a shared ocean space that is subjected to regulatory actions. Therefore, to dismiss “coercive integration” from the beginning as irrelevant to the region would seem to go against the dynamic and contingent approach to regionalism that is the strength of Greg’s conceptual framework.

Canberra shouldn’t read too much into Taylor’s words. In my conversation with her after the launch, she was emphatic that her words implied no endorsement of Australia’s integration agenda.

In her Griffith lecture in Brisbane the same day, Taylor offered three examples of the “political strength of the collective,” to show what regional resolve and solidarity look like. First was the Rarotonga Treaty, which establishes a nuclear-weapon-free zone in the Pacific and was adopted by Pacific leaders in August 1985. Second was the Biketawa Declaration, adopted by leaders in 2000, which provided the framework for the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands, or RAMSI. And third was the Pacific’s “instrumental role in concluding what was perhaps the toughest global negotiation ever — the Paris Agreement.”

Australia was central to the nuclear-free zone and RAMSI; the Paris climate negotiations are a different story.

As an example of how our strategic instincts can be used by the islands, Taylor points to Australia’s establishment last year of the Pacific Fusion Centre, bringing together information from across the region on security threats such as illegal fishing, people smuggling and narcotics trafficking. Taylor says the centre is “region-led and owned,” aligning a regional priority with “the aim of Australia’s national foreign policy for stronger security integration across the region.”

Australia’s effort to assert its interests, influence and values in the South Pacific must grasp the “region-led and owned” mantra. The region, too, must adapt and accommodate as it becomes a sea of islands.

The South Pacific coming together is about identity, but also the forms and forces of cooperation that can reach towards regional integration. How best can the islands serve the needs of their people? Sovereignty and security — and identity and culture — are based on strength, not weakness; Australia and New Zealand should be natural sources of help in building that strength.

As Asia grows and pushes and demands ever-greater attention, Australia too often swings between being in and out of the South Pacific. Accepting a region-led version of the Pacific future will reduce the attention swings, bolstering Australia’s fundamental interests in the stability and economic progress of the arc that runs from Timor-Leste through Papua New Guinea into the islands.

Australia has spent decades adjusting to the reality that it must find its security in Asia, not from Asia. In the same way, Australia’s need to be at the heart of South Pacific security must be matched by an understanding of what beats in the heart of island regionalism; this is about identity as well as instinct and interests.

Australia can best serve its instinct in the islands by striving to be the first among equals. And achieving economic and strategic integration must be based as much on island needs as Oz interests. If Canberra truly believes integration is the answer, it’ll have to be built on that “region-led and owned” vision.

Fry argues that Pacific regionalism is more than an arena for governance, but constitutes a “regional political community — a term that connotes a deep level of commitment, affiliation and identity beyond the nation-state.”

The instincts of Australia’s history can embrace that idea of region. To hold the South Pacific close, Australia must hold the islands high, and help them to hold together. •