The Australian-born marine biologist turned aquaculture entrepreneur Neil Sims has a vision that would change the way we exploit the oceans for food. From his office on the Big Island of Hawaii, with the Pacific just a long stone’s throw away, he dreams of hi-tech submerged fish farms operating far out to sea.

Sims sees twenty or so mammoth underwater pens, each containing tens of thousands of prime sashimi-grade fish, hovering fifteen metres below the surface, and anchored ten, twenty, even fifty kilometres offshore. These huge farms would be maintained and cleaned by robot drones, monitored by streaming video sent via satellite, and run from shore by a computerised system of remote command and control.

“And when you want to harvest the fish,” he tells me over the phone from his office, “you would simply click a button and the cages would be automatically raised.” In my mind’s eye I see rows of football field–sized nets appearing majestically from a calm blue sea, sluicing off water, like the exposed aquatic lair of a James Bond villain.

“And you’d have the harvest boat pull up next to the pen and an automated process inside the cage would corral the fish,” he goes on, “and then they’d be pumped out and straight into the boat’s freezers.”

It’s an extraordinary image. State-of-the-art robotics meets modern-day fish farming to create a new industry: over-the-horizon aquaculture.

Articulate, enthusiastic and – despite having lived for decades in the United States – still sporting a recognisable Australian accent, Sims is evangelical about developing high seas aquaculture. “We have put a robot on Mars. We have landed a robot on a comet. Don’t you think we can operate a robot twenty miles offshore?”

Sims says projects of this scale could be up and running in the Middle East, in Southeast Asia and in North America by 2030. It’s a vision he concedes would see some environmentalists reaching for their Twitter accounts. But he also believes that in recent years most of them have come to see that aquaculture – if done properly, in a sustainable manner – can take a lot of pressure off our increasingly stressed oceans.

By the middle of the twenty-first century there will be over nine billion hungry mouths on earth, Sims points out, and it’s going to take all our ingenuity to feed them the protein they need. If, as the World Bank estimates, 60 per cent of all the fish eaten on Earth in 2030 will have been farmed, let’s hope this worldwide spike in aquaculture is done with the softest ecological impact possible.

Sims grew up in Austinmer, a beachside suburb of Wollongong. He was one of those kids who were fascinated by the natural world. When he wasn’t surfing or swimming, he was hunting the local wildlife. “I was chasing butterflies with a butterfly net on a bicycle,” he says. “I had an ant farm in my bedroom. I collected critters.”

And when he wasn’t playing in the ocean, he was reading Willard Price’s children’s books, particularly South Sea Adventure, with its teenaged heroes, Hal and Roger Hunt, collecting animals for their father’s zoo and surviving a shipwreck by deploying their knowledge of science.

Sims studied marine biology at James Cook University in the late 1970s and then worked in the Cook Islands as a teacher with Australian Volunteers Abroad. In his mid twenties he even became the director of Marine Resources Research for this tiny Pacific nation.

When his south sea adventure ended in 1989, Sims came home to Australia and got a masters in science at the University of New South Wales. Sims says most marine biologists end up working in universities or government, but this career path no longer appealed to him. He wanted to build something from scratch.

Sims ended up back in the Pacific on another island, this time working with the not-for-profit Natural Energy Lab at Kona in Hawaii. The NEL is a government-funded startup incubator where scientists are encouraged to commercialise their ideas. In recent decades it’s become a sort of mini Silicon Valley for aquaculture.

Eventually, after several tries, one of his startups took hold. The Kona Blue Water Farm raised kampachi (also known as Almaco jack or Seriola rivoliana) in large net pens just off the coast near Kona’s International Airport. kampachi is a sashimi-grade finfish native to Hawaiian waters. Sims and his partners worked out how to grow the fish to fingerlings onshore and then grow them out in the pens. Fast-growing and highly marketable, kampachi is a good fish to farm.

Sims left Kona Blue in the late 2000s and set up a new venture, Kampachi Farms. “The goal for Kampachi Farms is to commercialise and scale up the production of high-value species,” he says. But it aims to do this in an environmentally sustainable way.

Traditional aquaculture has three main problems. Fish farms located close to shore compete with other commercial uses, such as tourism and recreational boating. Farmed fish are fed feed made from other fish. You catch small fish – such as sardines – and turn them into fishmeal and fish oil for the bigger fish in your farm pens to eat. This puts a lot of pressure on wild stocks of fish. And fish farms produce a lot of waste – basically fish faeces and uneaten feed – that settles on the bottom below the fish pens.

Sims resolved to counter these problems by developing new feeds and by going over the horizon. He would grow his kampachi in their natural environment, the open ocean, far from shore. He would no longer be in constant competition with other water users, and any waste would be distributed far and wide by the currents. And he would feed his kampachi more sustainably.

“The way to do that is less reliance on wild stock fisheries, and less reliance on forage fish like anchovies, sardines and herrings which are used in fish meal,” he explains, “And if we can use microalgae or agricultural proteins and oils from corn or soya beans or canola, that’s the way we want to go.” One of the main backers of his research, not surprisingly, has been the Illinois Soybean Association.

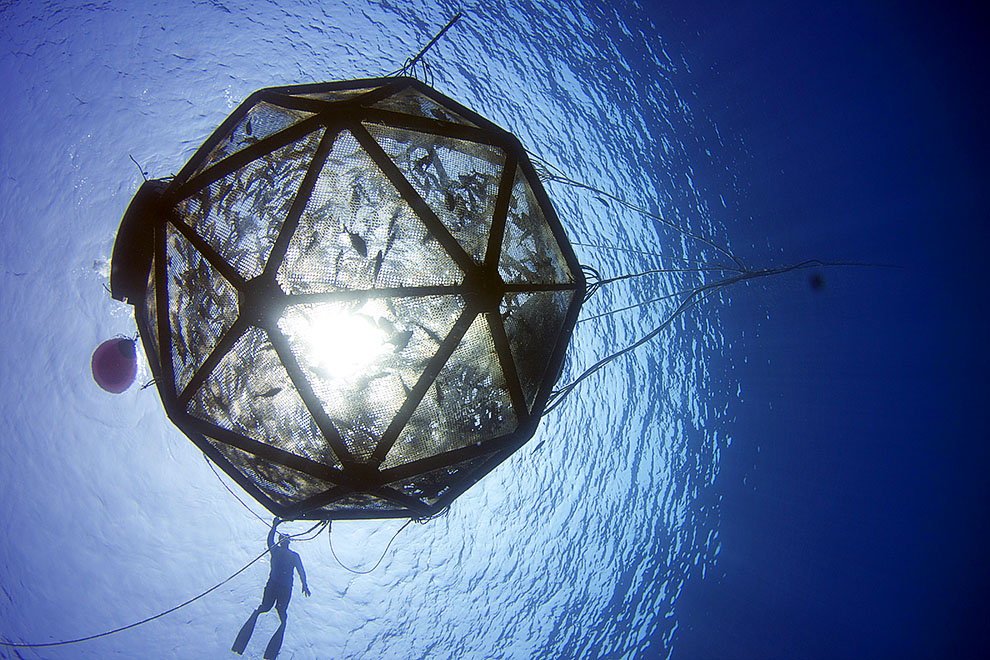

To test out his ideas, Sims called on new developments in aquaculture technology. He used an aquapod – essentially a large spherical cage covered in brass netting – developed by Ocean Farm Technologies. He filled the aquapods with his kampachi fingerlings and set them adrift in the massive circular currents that swirl in the ocean to the east of Hawaii.

Sims christened his research program the Velella Project, after a small, free-floating hydrozoan that’s related to the Portuguese man o’ war. In later tests Sims anchored the aquapods to the floor of the ocean on long chains, so they could still float freely, but on a constrained radius. He discovered that he could feed his fish and maintain the aquapods using a supply boat and divers. And, most importantly, he found that the kampachi grew well, that most of them survived and that there were no disease problems. The kampachi liked their new living arrangements.

Early on in the Velella Project, when the research team was contemplating using drifter cages, Sims realised that they needed help from a defence contractor, “one of those companies that uses satellites and communications, that flies drones over Afghanistan,” to manage the aquapods and their precious tenants from onshore. And three days later Lockheed Martin called him.

The defence industry giant was on the lookout for ways of making a peaceful buck from its war-making technologies and had found Kampachi Farms on the internet. With Lockheed Martin’s help, Sims is developing and refining the systems for monitoring and feeding his offshore kampachi.

So the sushi train has already left the station, it seems,when it comes to open ocean aquaculture. And Sims’s vision is shared by many other aquaculture entrepreneurs.

Off the coast of Panama, for example, Brian O’Hanlon, the founder of Open Blue Sea Farms, is already producing commercial quantities of cobia – a popular fish for sports fishing – in the world’s largest offshore fish farm. O’Hanlon – who might be described as the Elon Musk of aquaculture – uses a series of huge diamond-shaped pens to raise his stock of a million fish.

And just this month it was announced that Don Kent, CEO of the Hubbs–SeaWorld Research Institute, a research nonprofit partially funded by SeaWorld, is set to create the largest fish farm in the United States, four miles off the coast of San Diego. The Rose Canyon Fisheries, as it’s called, would consist of forty-eight cages anchored to the sea floor in an area as big as New York’s Central Park.

Sims is obviously in a race to perfect the next big thing in aquaculture. In La Paz, on Mexico’s Baja Peninsula, his company is developing a commercial kampachi farm, using large cylindrical pens four kilometres out in the Sea of Cortes. He is working on this project with British seafood millionaire Toby Baxendale and Norwegian fishing industry veteran Bjørn Myrseth.

Back in Hawaii, meanwhile, his collaboration with Lockheed Martin is bearing fruit, as his director of research demonstrated at an aquaculture conference in Seattle not long ago.

“He was sitting in the lobby of the convention centre with a bunch of people crowded around,” Sims explains, “and he’s pushing these buttons on his iPhone, and pulling up this video of the fish in the cage. And people are saying, ‘What are you doing?’ ‘I’m feeding the fish. In Hawaii. In real time. How fast do you want me to feed them?’” •