Geoff Dyer has been interested in endings for a long time. Nearing completion of his undergraduate degree in the 1970s, he made half-hearted applications to do a doctorate about “how novels end.” He was after a grant, not a contribution to knowledge, and the idea “fizzled out before it had even properly fizzed.” Done with academic aspirations, he “drifted into the life of unsupervised and unfocused study.”

Several decades and many books and awards later, contemplating his own experience of “the changes wrought by ageing,” Dyer has returned to the topic he thinks has been his theme all along: giving up. A passionate follower of tennis, it seemed important to finish his new book, The Last Days of Roger Federer and Other Endings, before the retirement of “Roger.” Dyer has never met Roger Federer but it’s still just Roger, “always and only Roger.” Then, a year into the writing, Covid struck and much of the book “ended up being written while life as we know it came to an end.”

Dyer is an endlessly original writer, the author of books with arresting titles about music, art, travel and much more: But Beautiful, about jazz; Out of Sheer Rage, about D.H. Lawrence; a collection of essays, Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered To Do It, about almost everything except yoga. In The Last Days, he marshals testimony from these passions to explore “things coming to an end, artists’ last works, time running out.” It’s not “a comprehensive study of last things, or of lastness generally,” more “a congeries of experiences, things, and cultural artefacts that, for various reasons, have come to group themselves around me in a rough constellation during a phase of my life.”

A clutch of book and movie titles illustrates the pull of “The Last…”: of the Mohicans, Tycoon, Picture Show, Emperor, Year at Marienbad, Tango in Paris. Coupling The Last with Summer seems especially beguiling. There are subcategories of endings and striking examples. “We love a crook’s last heist, ‘After-this-one-I’m-out.’” Armies and artists can meet perversely quick ends after “catastrophic early success.” Some experiences, like reading Edith Wharton, are more blissful because they have been deferred, savoured nearer the end than the start of a reading life. The temple built and destroyed each year at Burning Man acquires spiritual power at speed, in part because those who come to each temporary Black Rock City know and accept that the temple is about to burn.

One way to end is to quit. That can take guts, a kind of “self-discipline normally associated with persistence.” You quit on a book that is giving you no pleasure: “Just because something’s a classic doesn’t mean it’s any good.” You quit on a film, that “unforgiving medium” where there is “not even the possibility of redemption after the first botched minutes.” You long to quit on a poetry reading, even one you are enjoying, grateful for the wind-up words: “I’ll read two more poems.”

Having quit, extra endings can be generated by Coming Back. Artists do this — Jean Rhys and Duke Ellington are among Dyer’s exemplars who did it while still alive. J.S. Bach, Nietsche and van Gogh outdid them by rejuvenating from the grave. But it’s sport that’s the home of comebacks. Tennis seems tailored to produce them. The winner must win the last point. There is no end until then, no lead that cannot be run down. Every champion has come back from the clifftop of “match point,” that single point their opponent might have won but didn’t, an ending deferred then turned around.

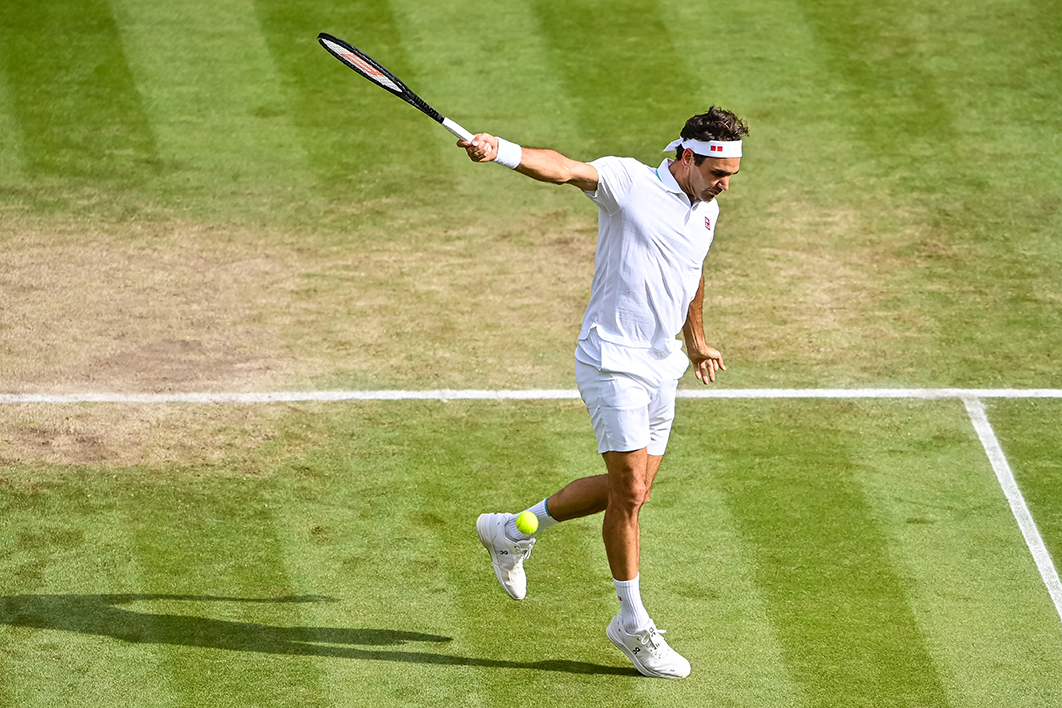

Without being able to read or play a note of music, Dyer has written superbly about it. Tennis he plays, twice a week, on courts beside the Pacific Ocean at Santa Monica. “The glow of those four hours suffuses the whole week,” he says. It exhausts him now, leaves him unable to do much else for the rest of the day. He is constantly injured. The book must not become “an injury diary or sprain journal,” but these pains are worrying. It’s “not just tennis elbow, it’s elbow elbow.” He stockpiles tennis balls, overgrip, shoes, racquets, hoping to “goad the poor corpus into eking out some kind of on-court existence even as it announces a daily increasing reluctance to do so.”

The endings and post-retirement lives of Roger’s predecessors at the top of the men’s game get special analysis. John McEnroe wrote not one but two memoirs, Serious and But Seriously, the second “focusing on the years he’d spent reminiscing about the period covered by the previous volume.” The champion he dethroned, Bjorn Borg, seemed “heir to some non-specific Scandinavian malaise: an all-court jumble of Hamlet, Kierkegaard, Ibsen, and Strindberg, held in check during the course of his career by a sweaty headband (or, conceivably, caused by the headband?).” Pete Sampras, whose record of fourteen Grand Slam victories Federer overtook, is “one of the most contented spirits in sport. He played a lot of tennis and then stopped playing tennis.”

It is still not clear if The Last Days made it to publication before Federer’s last day. He has not played a tournament since losing in straight sets in the quarter-finals at Wimbledon last year and has no ATP ranking for the first time in twenty-five years. Few really imagine he could win another major tournament. He has already staged his comeback, that astounding twelve months in 2017 and 2018 when, having failed to win a major since 2012, he won the Australian Open, then Wimbledon, then the Australian Open again.

He is supposed to be playing the Laver Cup in London in late September, an exhibition event where he will make up an old guard Team Europe with Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic and Andy Murray, followed by the Swiss Indoors in his hometown Basel. Attending but not playing Wimbledon two months ago, he talked about coming back “one more time,” a last summer on the lawns. Dyer would love it, but he knows it’s over. Roger Federer might get back on a court, even a centre court, but the era when “aesthetics and victory could go hand in hand” is ending.

A writer is naturally interested in how endings creep up in his chosen craft. Dyer’s poorly paid relatives looked forward to their retirements. “It was a form of promotion, practically an ambition.” Writers, he thinks, are more likely to keep to themselves their declining ability to form useful sentences or convince publishers to publish them. And “If part of the job is sitting in a chair at home with your feet up, reading, then the difference between work and retirement is imperceptible.” Retirement, for Dyer, will be “the phase of life in which I will do nothing but watch tennis.”

One of the many blurb writers who have tried to encapsulate Geoff Dyer called him “insouciant.” It is true but not wholly true. “Wouldn’t it be marvellous if it were possible to be a serious writer without taking oneself at all seriously?” he muses. “Not just socially, that’s easy…; I mean while actually doing the work.” Having published eleven books of non-fiction and four novels, Dyer has lived with the daily effort of finishing projects while fearing each might be the end of his writing life. The words wind up insouciant; the work that produces them is insistent.

Dyer writes absorbingly about Beethoven’s and Turner’s “late” periods. He contemplates adding a writer to complete the analytical triangle with the German composer and English painter, but rethinks the device when he realises he has one already.

At the US Open in 2021, like everyone else, Dyer was stunned by Emma Raducanu’s victory. In only her fourth tour-level tournament, the eighteen-year-old won her way through three qualifying rounds to make the main draw, then seven matches in a row without dropping a set. No qualifier had ever made the final, the last match, of a Grand Slam. Even more startling: Geoff Dyer found he was “starting to forget about Roger.”

A year on, the players are back at Flushing Meadow for the 2022 Open and Raducanu has been knocked out in the first round. Dyer might be in New York, or watching on television. As likely, he’ll be out in California, on the Ocean View courts, his “long limbs flailing away,” chasing down every ball he can. “I’m not going anywhere but if I were I’d be going out on my shield even if the shield, in my case, is a desk.” •

The Last Days of Roger Federer and Other Endings

By Geoff Dyer | Canongate | $39.99 | 283 pages