1

MANNING CLARK fascinates us. To use one of his own high-blown expressions, he dreamed the big dream. To use Woody Allen’s expression, he wanted to eat with the grown-ups. He had the temerity to imagine that he could somehow fashion literature from his country’s history and his vivid and melodramatic quest to understand his own experience.

And his dream was about us, about our history. He conveyed his sympathy for his characters, their yearnings looming as large in his narrative as their achievements and defeats. This was bound to irritate those with a more literal turn of mind; it also meant that when Clark waded into ethically or ideologically contested territory, his meaning was bound to be misunderstood. Indeed, as the ideological backdrop suddenly switched after the fall of the Berlin Wall, things turned positively poisonous.

On the other hand, it is painfully unclear what Clark achieved. His monumental six-volume A History of Australia is a very strange beast. The many factual inaccuracies may be nothing more than minor embarrassments, but what might they portend?

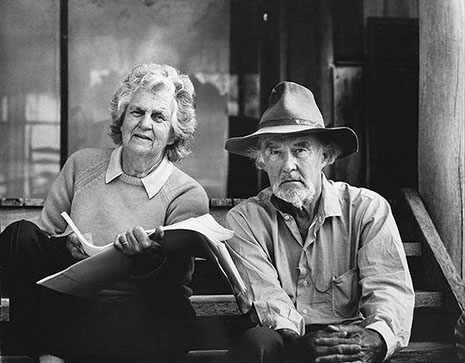

Count me among the fascinated for all these reasons, but also because I lived in a converted garage out the back of Clark’s house. I lived there for only a year, but for the best part of a decade I was either resident or a frequent visitor, and I got to know Manning and his remarkable wife, Dymphna, fairly well. So I devoured Mark McKenna’s new biography of the Clarks (for it is a biography of both, making Manning’s debt to Dymphna quite plain).

2

Clark attempted to write in an anachronistic genre – history as myth à la Thomas Carlyle. In principle, one can’t see why this could not or should not be done, but it’s hard to think of a single success in bringing back a distinct but defunct literary genre.

The problem runs deeper than that. Clark’s life was centred on his own experience to a degree that some might call pathological. McKenna stops short of describing him as a narcissist because he says narcissists are not consumed with doubt. I’m not so sure. In any event, however one describes it, Clark was so intensely preoccupied with himself – his mortality, his high ideals, and of course his failure to live up to those ideals – that there was little room for much else in his life.

McKenna had access to Clark’s diary and correspondence, including a massive cache of letters between Manning and Dymphna from their courtship (handily for biographers, much of it spent apart) right through to his demise in May 1991.

The newly betrothed couple each received scholarships enabling them to spend two years in Europe (a difficult thing to achieve in a much poorer world than ours and not something to throw away lightly). Dymphna went to Germany to further her remarkable abilities as a linguist while Manning went to England. From Oxford, in panicked loneliness, Manning sent Dymphna daily letters full of high-feeling prose declaring his love and inability to live without her. Though her letters are lucid, expansive and very affectionate, indeed loving, her inability (or was it unwillingness?) to respond in kind inevitably led to recriminations in Manning’s return correspondence.

He visited Dymphna in a Germany still recovering from Kristallnacht, which had occurred only two weeks before. He eventually got her to marry him and abandon her studies to join him in Oxford. The plan had been to marry back in Australia. There was danger in Germany, but Dymphna later felt that she should have stayed longer.

None of this kind of emotional turmoil is unusual for those in their early twenties. But it went on and on. Whenever Dymphna was away from him, Manning would write intense daily letters seeking her support. More often than not, this would lead to the same kind of standoff as had occurred in their earlier correspondence.

Manning’s infidelity with Pat Gray from about fifteen years into their marriage and then with other women on a number of subsequent occasions usually ended with Dymphna’s leaving him. On the last of these occasions she moved to Brisbane and took a job as a nurse’s aide (cleaning and menial chores – just what she endlessly did for Manning in Canberra). Even on such occasions, he wrote daily, and he lobbied his partners in adultery (usually successfully) to join him in begging Dymphna to return – for Manning’s life and his great quest was impossible without her.

3

I was certainly aware of the Clarks’ sensitivity to those who had turned against them. As one who saw their extraordinary hospitality, and their kindness to people who were able to offer little worldly benefit in return, it is easy to understand how they felt. Still, as McKenna shows us, it wasn’t as one-sided as that – or sometimes wasn’t. Not only was Manning as thin-skinned about criticism as he was about the failings he perceived in his wife’s affections, but he also reacted to scholarly criticism with extraordinary vigour, exhibiting a desperation that seems to have undermined others’ confidence in him. Receiving an advance copy of a fairly negative but well-grounded scholarly review of volume one of the History due to be published in Nation, Manning wrote to the magazine in an attempt to block publication and enlisted the doyens of Australian history – Max Crawford and Keith Hancock – to intercede on his behalf.

These tactics worked surprisingly frequently. In this case, though, the editor of Nation, the redoubtable Tom Fitzgerald, would not agree to suppress the review. But in the eye of the maelstrom, the reviewer had second thoughts. Nation ultimately published the piece as written, but with a bizarre apologetic postscript conveying its author’s chastened confession that in his “anxiety to defend Protestantism” he had treated Clark unjustly. “This is simply the impact of the book on me,” he confessed, “the result of my harsh, personal selection from so many riches and insights.” Nor, he confessed, had the review recognised that “the personal idiosyncrasy of an historian is often the very groundwork of his insight and originality.”

Manning would refuse all contact with those whom he felt had slighted him. One could say he was thin-skinned, but it might be more accurate to say that he almost lacked a skin – as if he had a wound over which skin wouldn’t grow, and the slightest touch set it off again.

Ultimately this was the downfall of the grand history.

4

Though Clark regretted the factual errors in his History, they alone don’t vitiate his broader intent, which was to write a history that would live as literature by rendering the story of Australia according to his grand themes. But Manning’s mistakes are a symptom of a deeper problem: as the repetitions mount and the characters act out Manning’s mental world, the drama flags and the scope of the narrative narrows.

McKenna’s biography contains several examples of people writing to Manning to correct points of fact and interpretation. He portrayed Curtin as morose – not unlike guess who? – but Curtin’s daughter wrote to tell him that he had made numerous factual errors, her father was not morose, and her mother would never have given Curtin an ultimatum that she’d not marry him if he wouldn’t give up the drink. (Manning had a difficult relationship with alcohol, largely kept at bay by teetotalism in his later years.)

But the ultimate shame is not that Manning got some facts wrong about his characters. Rather, the problem is that his archetypes – whether it is Alfred Deakin, John Curtin or Henry Lawson – never really expand into well-rounded characters who are uniquely themselves. The archetypes are a side of Manning in fancy dress. Hell in the heart, uproar in the trousers, wondering what went on in the mind of a woman, wondering what it was all for. Clark cannibalised the material for scenes that he could transform into stories he wanted to tell.

And so Clark gets caught between two stools. His work is not and does not aspire to be historical fiction. On the other hand, so much of his focus is on the inner drama that his history is full of what might be called “elaborative fiction.” Here is Clark describing the moments after Ned Kelly’s capture:

Matthew Gibney, the Vicar General of the Catholic Church in Perth, who happened to be at Glenrowan, began to prepare Ned for his journey into the kingdom of perpetual night. He knew what had driven Ned mad; he knew the meaning of those words “Mad Ireland made him”; he knew how the English had allowed the most beautiful island on God’s earth to become a land of skulls during the Great Hunger of 1846–47. But he knew, too, the reminder of his Divine Master that any man who was angry with his neighbour without cause was in danger of hellfire; he knew of the compassion of the Galilean for those outlaws and vagabonds who wandered over the face of the earth with a private hell in their hearts. So on that railway station at Glenrowan, Matthew Gibney began to tame Ned and to prepare him, desperately late though it was, for redemption and acceptance, to get him to see that though men find some things right, and some wrong, to God all things are fair, and just, and right.

The passage is certainly unusual by the standards of modern history, but because it is fairly clear that the historian is elaborating on things he cannot know, it is not deceptive. Yet the elaboration can never really be more than a rhetorical device, as this is fundamentally history and not historical fiction. Though what is transpiring in the hearts of Ned and Matthew Gibney is at the centre of the author’s concern, it cannot be given its own substance and development as part of the story, for then, in the complete absence of legitimate sources, the work would cross over into historical fiction proper.

In fact the passage just quoted is not from the History but from an excellent 1968 essay on Kelly. In this context the passage works to convey one of the central points of Clark’s essay. Kelly walked the earth in the fog of the present, unsure of what would happen next or what he would make of himself. Clark’s story is of a man meeting his destiny – as we all must.

But this technique descends into banality and bathos when sustained over six volumes. History made mythic literature becomes costume drama. Our knowledge of the past does not deepen as we enter the world of the characters. Nor, paradoxically, do we learn anything new about Clark’s mental world, for that would require the historian to engage creatively – beyond simple identification – with the material. We have entered a literary echo chamber. Ken Inglis’s litany of adjectives sums up the six volumes’ prose – “glowing, incantatory, allusive, evocative, archaic, banal, repetitive, threadbare.”

For all the ambition of its conception, Manning (and, I think, Dymphna) always feared that the History was a grand failure. He concluded his Boyer Lectures with words that could be read as a kind of literary affectation, a knowing intimation of the inevitable doubt in the mind of the grand quester. Or they can be read more prosaically. “I was very lucky: I had a great dream,” he wrote. “My great regret was that I was never able to find the words which would enable me to portray the child of my heart.”

In 1967, the year before the publication of volume two, he gave a lecture full of admissions about the weaknesses of the History:

I remember, and like all journeys, there were and still are moments when one regretted leaving the winter palaces – when one wondered whether it was all folly – the peaks were always out of reach. Yes, and I would do it again, because, may I say it, the vision was right, the execution bad.

5

Despite all this and overblown as it was, the Clark’s History was a considerable achievement:

• As McKenna argues, Clark’s was the first post-colonialist history of Australia. From its opening, it cast Australian history as a European, not a British, drama.

• Clark’s portrait of Australia as an historical theatre in which the competing values of Enlightenment, Protestantism and Catholicism clashed is a fine framework on which to hang the story of our country and its great characters.

• Its embrace of narrative and his determination to tell a story for the people of Australia was a bold affirmation of the primacy of history as part of the human conversation over its institutional manifestation in the academy.

• Clark’s passionate adherence to a unique Australian sensibility figures as early as his ex-pat years in London – earlier than it came to many of those cultural patriots of the postwar world like White, Boyd and Nolan, with whom Clark became a fellow traveller in building a new Australian sensibility.

6

Despite – and in some senses because of – the failure of the History, what Manning Clark achieved was worthy of the grandness of his quest and the doggedness of his devotion to it.

It is not incidental that the passage on Kelly quoted above is from a much shorter work – an essay. For Clark’s style really was at its best in shorter pieces. His essays and speeches are almost invariably fine things to read. I heard him give several speeches, and they were simply electrifying.

I remember an end-of-year dinner at Burgmann College at the Australian National University. Many speakers in such an environment are keen to show how “hip” they are, or at least once were. Or how important they are now. Manning began in a very soft, almost breaking voice. He had a microphone, but he was still almost impossible to hear clearly through the din, which soon died down to occasional chatter.

Their bellies full and the year behind them, some people tittered as they sipped on their drinks. Manning opened with a nursery rhyme.

Old Mother Hubbard

Went to the cupboard,

To give the poor dog a bone:

But when she got there,

The cupboard was bare,

And so the poor dog had none.

More tittering. Though Manning showed no anxiety to hold his audience, the room stayed quiet enough to hear and be drawn in. He spoke of characters from the past who had set out bright-eyed and bushy-tailed on their journey through life, just like his audience that night. But they had come to wonder whether, despite all their talents and their reserves of endurance, the cupboard might be bare.

What if one went to the cupboard, and found it was bare? What then?

Towards the end of his speech he was almost inaudible, as if he were breaking down. Perhaps he was. Perhaps he was putting it on. His newest biographer leads us to speculate that it was a bit of both. But everyone could hear, for they were in hushed silence, straining to catch his words. Manning made them feel the idealism of youth not with the usual flattering clichés – “our youngsters are our future” – but by confronting them with the seriousness of the human predicament – their predicament. And the sacredness of a life’s journey. “You have to remember there are dogs outside the holy city.”

After perhaps twenty-five minutes on his feet, he concluded. He seemed almost to have petered out. There was a pause while people wondered if he’d stopped. And then there was rapturous applause. It was a remarkable performance. Indeed, in his unique way I think he was the best speaker I’ve ever heard. What was on display was a very complete kind of performance: the heart was paramount, and yet the talk emerged from a very deep learning and knowledge of his subject, and the bloody-minded steadfastness of effort, by now two decades old, with which each volume of his History had been wrought.

7

The other thing that McKenna’s biography touches on but that looms larger for me is this: Manning played the fool – the sort of fool to be found in Shakespeare’s plays. Manning made an art form of speaking the truth elliptically, strangely – playfully. His charisma as a lecturer was partly based on his unpredictability. He was constantly doing strange but very funny things – like singing in his lectures. In his letters to Dymphna and to others he is expressing his phobias and foibles, but he’s also acting the fool, full of wide-eyed naivety and the truth-telling of a child (which is not to say that he wasn’t up to his own tricks).

When each volume of the History came off the press, Manning would go to quite extraordinary lengths to greet it, sometimes driving hundreds of miles. He would post notes to his parents on their gravestones, and then keep photos of their graves with the notes on them. He might have courted celebrity and enjoyed the good opinion of those in high places, but he would frequently accept invitations from and spend his precious time on people and organisations that could add nothing to what ultimately became his considerable fame. Patrick White conveyed the acid of his disappointment to Dymphna on one occasion when unable to be put through to Manning: “I suppose he’s opening some country dunny in Woop Woop.”

McKenna makes it clear that by May 1991 Clark felt he was dying. This was a man who was leaving notes around the house both for Dymphna and for his biographers. He was a hypochondriac, yet he rejected the precautionary hospital stay recommended by his doctor. And he still accepted an invitation to visit Adelaide to speak – a trip he cancelled from what became his deathbed later on the same day. The biography doesn’t say, but I think it was a pretty low-profile engagement.

For all his self-obsession Manning could also be hospitable to the point of foolhardiness. His domestic hospitality, the endless dinner parties in which students, acolytes and hangers-on like me were mixed with visiting academic and literary dignitaries – the David Maloufs of the world – were more of an imposition on Dymphna than on himself. I recall the numerous times I was invited to make the trip with him down to his beach house at Wapengo. (As Dymphna would point out with great hilarity to anyone interested, Wapengo appears, ridiculously enough, on a map of major settlements in New South Wales in 1850 in volume three of the History.)

We piled into the car with Tuppence, an ageing black ball of canine love and goodwill, and co-subject of Arthur Boyd’s lovely portrait of Manning. Along the way Manning would stop and pick up virtually any hitchhiker. In they’d squeeze with their luggage, their pets and their BO. They’d be invited to stay at Wapengo. Almost anyone could come to Wapengo, which, as far as I know, remains as a kind of monument to that level of unconditional hospitality – with the Clarks’ marvellous weekender designed by an architectural student friend, the endless plantings of native trees by Dymphna and the hippy mudbrick hut at “The Clearing.”

There’s not the space to elaborate fully on the wonderful Dymphna – whom I knew as a mass of friendly wrinkles and raucous laughter – but suffice it to say she was in on the act. Generous and straightforward, indeed to the point of guilelessness, she nevertheless seemed incapable of expressing herself without an irony which left room for meanings other than the literal words that passed her lips. There was a hint of parody of herself and the Great Man in almost everything she did. “Manning can see into people’s souls,” she’d opine loudly, with mock seriousness, before dissolving into her distinctive laughter.

She combined her general irreverence for social convention with her reverence for her husband’s status as a fisher among men by passing through US Customs with a large, frozen but gradually thawing Australian salmon. Manning had caught it the previous weekend at Wapengo. It was wrapped carefully in newspaper and bundled into a manila folder unconvincingly – though not entirely incorrectly – marked “printed matter.” The fish was greedily consumed that night at the home of their daughter Katerina in Yale, New Haven. I have little doubt, though she did not confirm it for me, that some of Dymphna’s delicious mayonnaise with rosemary and dill from her capacious garden was also stowed away on the salmon’s intercontinental journey.

8

In thinking of Clark, I think of Oscar Wilde’s comment that he put his talent into his work and his genius into his life. Of course, Wilde’s life really was one of genius, crowned by martyrdom for his cause. Clark achieved nothing on that scale, and indeed, in my opinion, nothing to rival Wilde’s greatest plays, but one of the things I thought before I read McKenna’s biography, but which becomes much plainer having read it, is that Manning’s magnum opus was a grand quest. If I am right that it is what Manning feared it was – a grand failure – that makes it in some senses a grand folly. But life moves in mysterious ways. And the History was the route Manning took – perhaps the only one possible – into the life he wanted to lead, the character he wanted to play.

And while the point of all those days rising before dawn to climb up to his study was assuredly enough the work, it was also the work in the life. As we all do, Manning narrated his life to himself. Then he turned that narrative into his subject. He did so quite self-consciously, relatively early on in the journey, and he returned to it both during the writing of the History and as a refrain afterward. Like many great writers, his subject was himself, and his life. He wasn’t a great writer, but he was a fine writer and some of his shorter pieces and parts of the six volumes are magnificent, as were many of his speeches. So also is his autobiographical writing about his own determination to go to the cupboard even at the risk of doing an Old Mother Hubbard. Even if the History is a grand failure, Manning Clark did not go away empty-handed, and neither did we.

His ambitions were grand. And in a paradoxical way he achieved them. I’m not thinking of the adulation that came his way, as much as that might have buoyed his hope that the work had been worth the effort. Rather, he got to eat at the grown-ups’ table, and there was an open invitation for any of us to join him. •