On Wanting to Change

By Adam Phillips | Penguin Books | $16.99 | 160 pages

If you were to judge this slender book by its cover, your first impression might be that it is a tequila sunrise. Judging from its title and blurb, though, you might decide it is an examination of the urgings and obstacles to personal change. In fact, it is neither. It is an extended meditation on the idea of conversion, whether personal, religious or political.

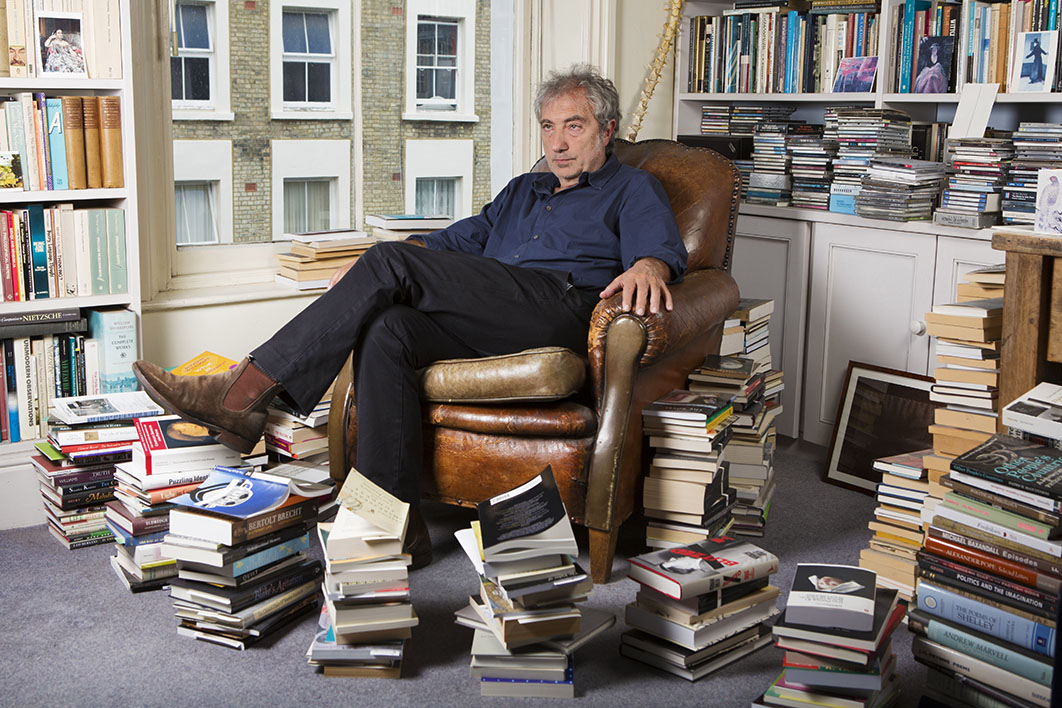

Adam Phillips is a prolific British essayist on matters literary, cultural and psychoanalytic. As a practising psychotherapist and general editor of the Penguin Modern Classics translations of Sigmund Freud, he has serious credibility as a psychoanalyst, but his style of psychoanalytic writing refreshingly lacks the usual heaviness and homage to the master. In what is a fundamentally interpretive approach to understanding human behaviour, he treats the psychoanalytic tradition as a source of interesting ideas and inversions of common sense. His books have put that approach to work in elegant discussions of everything from tickling to monogamy (“A couple is a conspiracy in search of a crime”).

His new book began as four lectures on conversion, in the sense of a dramatic process of revolutionary change, a rupture or break from the past. It begins with an exploration of our tendency to view conversion as an outcome of seduction or brainwashing. Enlightened folk favour a more gradual and educative approach to change, Phillips argues, rather than what they see as escapes from complexity into submerging group identities. For all the current talk of becoming one’s best self, most of us just want to become better by degrees.

For Phillips, the psychoanalytic notion of conversion, in which the emotion attached to a troubling idea is transformed into a physical symptom while the idea itself remains unchanged, offers an alternative way to think about it. We can then see personal conversions as a kind of substitution rather than a genuine transformation. Apparent conversions may be ways of staying the same.

Phillips’s second chapter continues the theme of our ambivalence towards personal change — wanting but also dreading and resisting it, recalling Freud’s quote that neurotics will defend their neurosis “like a lioness her young” — and our inconsistent beliefs about it. Although we may be sceptical of dramatic positive change, Phillips observes, we increasingly embrace the idea of trauma as a cause of negative transformation. People also wrestle with the competing forces of stability and disruption: biology and fate on the one hand; choice and self-fashioning on the other. They are both changed and un-changed, with a sense of having a true self that is out of reach of the false one they inhabit.

These conflicts and self-doubts sometimes motivate efforts at personal conversion, with results that can be less transformative than advertised: “one of the ways the new makes a name for itself is through the rhetoric of hyperbole; great claims are made, but over time the past begins to show through.” It is difficult to let go of a former identity. Therapy might offer a secular form of conversion, but the change it offers is less than dramatic. Sometimes “people aren’t cured, they just lose interest in their symptoms.” Close studies of famous converts Paul and Augustine round out these explorations.

Conversion in the political sphere comes in for a less satisfying analysis through ruminations on the ideas of French theorist Étienne Balibar and American political scientist Wendy Brown. To Balibar, political transformations involve a conversion of violence into civility. Phillips suggests that believing in such a transformation relies on an optimistic but sometimes naive view of the mutability of human nature. Utopian political ideals depend, he argues, either on the belief that human nature can be reinvented or on the recovery of an idea of human nature that is supposed to have been lost. For people seeking political transformation, what ultimately has to be converted is doubt about the possibility of change.

Phillips’s final essay explores conversion from the standpoint of the outside observer. How much are converts really seeing new truths and how much are they just seeing things as a new group defines them to be? Conversion, he suggests, is often a matter of identifying with someone else, although converts tend to believe they are becoming more truly themselves. Socrates is put forward as an authentic self-fashioner who made himself unique without attempting to become someone else; and the psychoanalytic theory of perversions is examined for clues to what drives some sorts of pathological conversion.

There is something almost hypnotic about Phillips’s writing. He assembles simple words into complex thoughts, cas-ually cites French intellectuals, drops aperçus that demand a second and third reading, and then heads off on new tangents. His writing has a certain cadence as well. The classic Phillipian paragraph starts with a few unshowy statements, follows them with an arresting remark in parenthesis, builds to a conclusion and ends with an aphorism that may not qualify as a grammatical sentence (“Targets that must be missed in order to be met”). The rise and fall of these paragraphs is transporting, and even if they rarely deliver an obvious message or hammer a lesson home, the reader is left with a sense of having been taken on an intriguing journey.

It would be a mistake to read Phillips seeking guidance on how to change oneself or a systematic theory of the nature of conversion. Any reader hoping for an answer to why, at this historical moment, some things are believed to be convertible (sex and gender) and others not (race and sexual orientation) will be disappointed. Phillips has no advice to give or grand theoretical statements to make, just reflections. Those reflections are food for thought, and readers wishing for a second course can look forward to the publication of its sequel, On Getting Better. •