The design of the National Energy Guarantee is extraordinarily complex. Its merits are in dispute. But the politics is simple.

The government wants a deal the Coalition can unite behind — one so nuanced that both its realists and its climate change deniers can support it — while convincing the public that the policy will actually reduce prices, improve network reliability and reduce emissions.

To achieve that, the plan has to win the support of the electricity industry — which, by and large, it has done — the states, which appear to be holding out, and probably the federal Labor Party, which is yet to declare its hand.

Long negotiations have seen the plan’s details change repeatedly, and there will be more changes ahead. The silliest comment being made now is that this is “the only plan on the table.” Yes, this week, it is. But before that we had many other plans — the Finkel report’s clean energy target, the Climate Change Authority’s emissions-intensity scheme — as well as many variations of this one, with more to come.

The negotiations that really matter have been within the Coalition. They have been between the Liberal Party and the Liberal Party — and, of course, the National Party. The Turnbull government and its Energy Security Board have made numerous concessions to try to win over those in the Coalition ranks who are opposed to doing anything to tackle climate change. The most important of these concessions is that it offer no concessions to Labor.

So far, Malcolm Turnbull and Josh Frydenberg have offered no significant compromise to win the support of federal Labor or the Labor-run states. That may change in the weeks ahead. But right now it is asking them to give bipartisan endorsement to a deal that has been negotiated entirely within the Coalition, tramples on Labor’s own policy, and would mean that Australia effectively abandons our share of the Paris agreement to cut greenhouse gas emissions worldwide.

There are differences within Labor ranks over what to do, at least ultimately. In the short term, they are playing for time, and demanding that the Commonwealth decide its position first — in the Coalition party room — before asking the states to come on board.

The Turnbull government is insisting that the states agree to the plan first before it goes to the Coalition party room — where it could well be changed. The Labor states, not unreasonably, are insisting that the Coalition should decide first what its policy is, before putting it to them.

Who will give way? Would the government dare to put the plan before the party room before it has got the Labor states to commit? If not, why not?

If it does intend to make concessions to try to get a genuine bipartisan agreement, this might be the best time to reveal them. Otherwise, why expect Labor to endorse a policy that is radically different from its own — above all, one that would cut emissions from the electricity sector by only 26 per cent between 2005 and 2030 — which it had no say in drafting?

The consequences matter. In Paris in 2015, the Abbott government committed Australia to cut its total emissions in 2030 by at least 26 per cent from 2005 levels. While Tony Abbott wants Australia to now walk away from that, the Turnbull government still officially upholds that pledge.

But the cheapest place to cut emissions is in the electricity sector, where old emissions-intensive coal-fired power stations can be replaced with emissions-free energy from the wind and the sun — backed up by batteries and hydro storage. It would be prohibitively expensive to make similar cuts in Australia’s other major sources of emissions: agriculture, transport, industry and mining.

The emissions target for the NEG means that Australia would effectively abandon its commitment under the Paris agreement. If emissions in the electricity sector are to fall by only 26 per cent, it will be impossible to meet our commitment to reduce total emissions by 26 per cent.

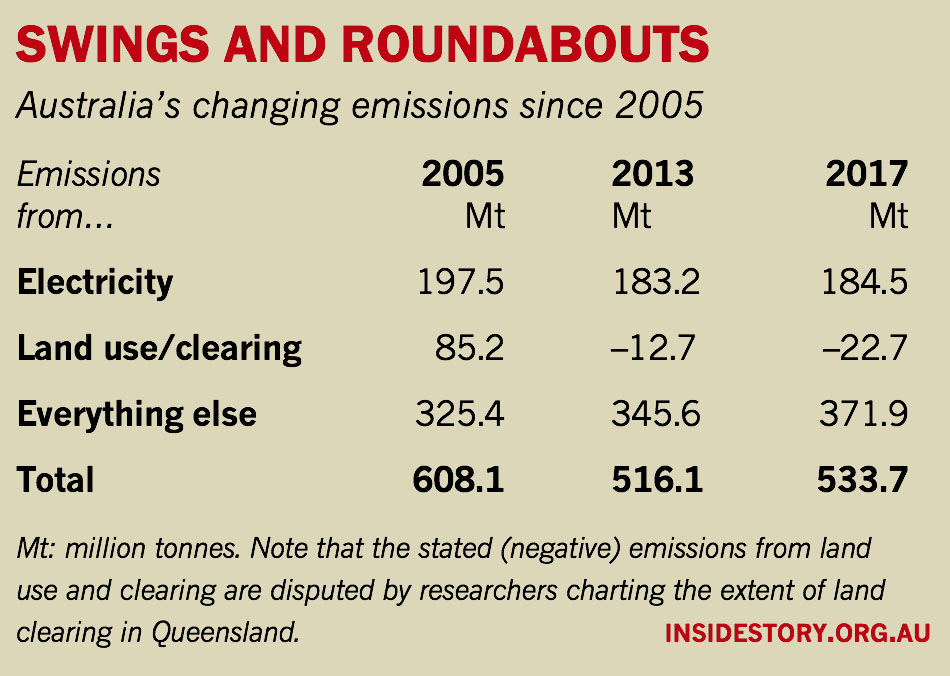

The government’s own figures show how Australia’s emissions have progressed since 2005:

Emissions from electricity generation in the second half of 2017 were about 10 per cent below 2005 levels and declining. But combined emissions in industry, transport, agriculture and mining were up 15 per cent and rising. It is completely unrealistic to expect that they can decline at the same pace as emissions from electricity generation — as the NEG targets imply.

Those who argue for the NEG as it stands — all the business groups and the mainstream media — are effectively calling on Australia to abandon its Paris commitment. They never admit that, and nor does the government, but it follows inescapably. How could Labor agree to that?

Well, Labor too is in the business of trying to win elections. And it knows that, above all, Australia is fed up with the climate wars that have divided us for the past decade. Ordinary Australians and the electricity industry just want an agreement, any agreement, that will end the debate, and allow us to move on to something else.

If the government refuses to compromise, Labor’s feet will be held to the fire. If it stands up for the Paris agreement, it will be attacked by the government and the mainstream media for wrecking the so-called “experts’ plan” to end the climate wars — and that could lose it seats and support to the Coalition.

If it accepts the NEG in its current form and effectively abandons the Paris agreement, it will be seen as betraying its supporters, like Kevin Rudd did in 2010 — and that could lose it seats and support to the Greens.

The short-term political equation is that Labor can lose seats to the Greens and still form government. But if it loses seats to the Coalition, it risks its chances to form government.

The longer-term political equation is that if Labor forms a government after accepting the Coalition’s emissions target written in law — as the Coalition is demanding — it will have to try to get the Senate (and possibly the states) to amend that law after the election. That would be difficult, even impossible; as I have argued elsewhere, Labor is likely to face an unfriendly Senate even if it wins comfortably in the House. But it is unrealistic to think that Labor can govern successfully with this policy.

If the Coalition can get the NEG past the Labor states, past the party dissidents, past the Senate, and then win re-election, we would have three years of the policy security its Energy Security Board has promised.

But energy companies will not make long-term investments if they are secure under only one side of politics. Long-term policy security — and the consumer savings the board predicts will flow from that — will come only if there is genuine bipartisan agreement.

This policy is not it. If the Turnbull government wants the NEG to have genuine bipartisan support, it has a number of options to make changes to achieve that. So far, it has rejected the lot.

● The only way to provide certainty to investors is through a bipartisan agreement on Australia’s overall emissions target for 2030. There is room to do so, because Labor’s leaders must be aware that their current target of a 45 per cent reduction in emissions is quite unrealistic. Instead, the Turnbull government has moved the other way, trimming Australia’s Paris commitment to reduce emissions from 2005 levels by “26 to 28 per cent” by 2030 to just 26 per cent.

● The government could have asked Labor to accept Australia’s Paris target, and in return set a realistic target to reduce electricity emissions by 2030 — say, by 45 to 50 per cent — to ensure it is met. Instead, the Coalition has pledged to reduce electricity emissions by just 26 per cent. Since it is not possible to reduce other emissions by 26 per cent, that ensures that Australia will not meet its Paris commitment.

● It could have offered Labor a mechanism that would allow the government of the day to change the emissions target, by setting it as a regulation. Instead, it is insisting that its target be adopted in legislation, so that a future government would need to pass another bill through both houses to amend it.

● It could have allowed state governments to set their own renewable energy targets to provide further emissions reduction. Instead, it insists that the NEG disregard these targets, making them useless, because lower emissions in one state would allow higher emissions in another.

This is not minor nit-picking. The Paris agreement is the most important international agreement of recent years. The commitments each country made are crucial to achieving progress, however inadequate, towards reducing the pace and extent of global warming. Australia already produces the highest per capita emissions of any country outside the Middle East. We cannot walk away from our pledge.

I have repeatedly defended the government’s commitment to cut our emissions by 26 to 28 per cent against criticism from the left that it is too small; in fact, it requires us to halve our per capita emissions in a generation. Yet with each year showing how real the threat of global warming is, it is bizarre that the target is now under attack, openly or surreptitiously, by those who wrote and supported it.

It is misleading to call the NEG “the experts’ plan.” Malcolm Turnbull created the Energy Security Board to sit above the three existing electricity agencies, and brought in his old colleague Kerry Schott, a veteran problem-solver who worked with him for years at the Turnbull Wran merchant bank, to come up with a fix that would meet his political objectives. And that she has done.

The plan is tailored to meet political objectives. And whether it can achieve its professed goals — knocking $150 off the average household electricity bill, guaranteeing electricity supply, and lowering emissions — is debatable for prices and security, and clearly impossible for emissions, where its own modelling predicts it will have virtually no impact.

The technical debates about the merits of the NEG are another story, which I will not enter here. It is certainly true that the plan now has consensus support from the electricity industry, but it is far from clear how great an improvement, if any, it will actually make. The supposed $150 per household saving appears to have been plucked out of thin air. The report’s claim that most of it will come from “unleashing new investment” is contradicted by its own modelling, which forecasts minimal change to generation capacity compared with what would happen anyway.

I can only refer those interested to the best of the criticisms: by Victoria University energy analyst Bruce Mountain in the Financial Review (paywall), by Giles Parkinson in Renew Economy, and by Simon Holmes à Court in the same publication today.

The case for the scheme has been put best by Australian Industry Group chief executive Innes Willox today in the Age. But his argument that the Labor states should just pass it now and try to fix it later really defies the political law of gravity. The time to fix it is now, before it becomes law. It would be much harder to do so afterwards.

The government has rejected other plans that were once the only game in town: the Finkel report’s clean energy target, and the emissions-intensity scheme for the electricity industry (Labor’s preferred option, and in my view the best politically plausible option that has been put on the table). And, of course, it rescinded Labor’s carbon tax, which by now would have seen an emissions trading scheme covering most of the economy.

The government rejected all of these because of opposition from party hardliners. For the same reason, it has refused to compromise with Labor now, even though it knows that without that, it cannot achieve a genuine, lasting bipartisan agreement that will unlock investment.

No company is going to build new coal-fired stations, or gas-fired stations unless gas prices fall. We now have three million homes producing solar power or hot water on their rooftops, but only a fraction of those producing solar power can store it for when it’s needed. And across the country, solar and wind farms have gone up far in advance of the batteries or pumped hydro plants that could store their power to use at peak times. Those crucial storage investments will be in doubt without a bipartisan blueprint to meet Australia’s Paris commitment.

So far, the Turnbull government has not even tried to reach a genuine bipartisan deal. The inescapable conclusion is that the Coalition in its current state is incapable of negotiating an agreement. If Frydenberg offered Labor a deal it could accept, that deal would be rejected by the Coalition’s own backbench.

That will not change until the Liberals and the Nationals have leaders like Gough Whitlam or Bob Hawke who are prepared to take on those in their own party who are blocking the way to a realistic policy. There is no sign of that now. It might be years away. ●