Rooted: An Australian History of Bad Language

By Amanda Laugesen | NewSouth | $32.99 | 320 pages

Back in the days when passengers mingled freely on Sydney trains, I once sat behind a man engaged in an animated conversation on his phone. He appeared to be talking to a solicitor about the unsuitability of the barrister appointed to a court case. “All this fuckin’ Mister this and fuckin’ Mister that,” he declared. “That’s not how we talk.” The obscenities peaked when he described his wife’s distress at the prospect of their son facing a murder charge. As I leant closer to catch the details of this dramatic story the man suddenly turned and saw me. “Oh,” he said. “Sorry about the language.”

It was a striking demonstration of the themes examined by Amanda Laugesen, director of the Australian National Dictionary Centre, in her new book, Rooted. The barrister’s language was too formal for his client’s comfort; the man was expressing his anxiety about his son with all the intensity that taboo language can provide; and I was a respectable matron who must be shielded from these words no matter how intrusive my interest. Class, education, ethnicity and gender were all in the mix. Yet it also seemed that bad language was essential to the urgency and emotion of the situation.

Rooted takes on the challenging task of speculating about the spoken language of the past. Using the written evidence, it traces the history of bad language in Australia from the beginning of European settlement, when the profanities used by the convicts shocked many early observers of the new colony. As the free settlement grew, so did the desire for respectability and concern about public language. But in the pastoral districts, bullockies were becoming notorious for the blasphemy they claimed was necessary to control their animals.

Laugesen’s narrative follows the broad changes that came with the growth of urban populations after 1880 and the development of larrikin language in the cities. When the first world war sent thousands of Australian soldiers to Europe, middle-class officers and English people they encountered were horrified by their easy use of “bloody, bugger and bastard.” The diggers’ magazines exploited the comic potential of these words, although they were also, as Laugesen notes, an expression of the fears of those facing death or injury.

Laugesen goes on to consider the attempts to control bad language from the 1920s onwards, particularly in print, and the restrictive censorship of literary writing in Australia right up to the 1980s when, as she puts it, bad language was “liberated.” She then looks at how new digital technologies have disseminated slang and obscenity in recent decades, encouraging a loosening of restrictions on dialogue in film and television.

Drawing on journalism, court reports and literary writing, Rooted provides a concise history of how certain offensive words and phrases have been used over time. Laugesen expertly synthesises a wide range of research into the place of bad language in Australian social history, tracing progress from a restrictive and snobbish puritanism to the “liberation” of offensive language.

Several of the historians cited by Laugesen argue that Australian bad language has been used to challenge authority, whether of British masters (in the case of the convicts), white bosses (Aboriginal people) or the patriarchy (women since the 1960s). In the nineteenth century this transgression was principally expressed in blasphemy, a cursing against the sacred in an age when religious belief was widespread. Even euphemisms that now seem innocuous — “bloody,” “gosh,” “gee whiz,” “crikey,” “hell” — carried a frisson of defiance of God. Nowadays, even children use them with little awareness of their origin. But they may still be used to indicate some sense of group solidarity and a resistance to respectability, as when senator Jacqui Lambie recently expressed concern for “the poor bloody students” facing increased university fees.

Blasphemy is one thing; sex and other basic physical acts are another. Over the past seventy years, censorship has focused on sexual words in publishing or broadcasting, and particularly the use of “fuck” and “cunt,” though the language of bodily excretion also has popular currency. As Laugesen explains, the literary censorship of the past was as much about the depiction of sexual acts as it was about the words that describe them in vulgar speech. To my mind, this makes the fiction writers more interesting than nineteenth-century court reports of specific word usage. Laugesen mentions Marcus Clarke’s His Natural Life but not that his name became a euphemism for sodomy. She refers briefly to Joseph Furphy’s inventive substitutions in Such Is Life without appreciating his ingenious attempts to say the unprintable as a challenge to the limits of the novel form.

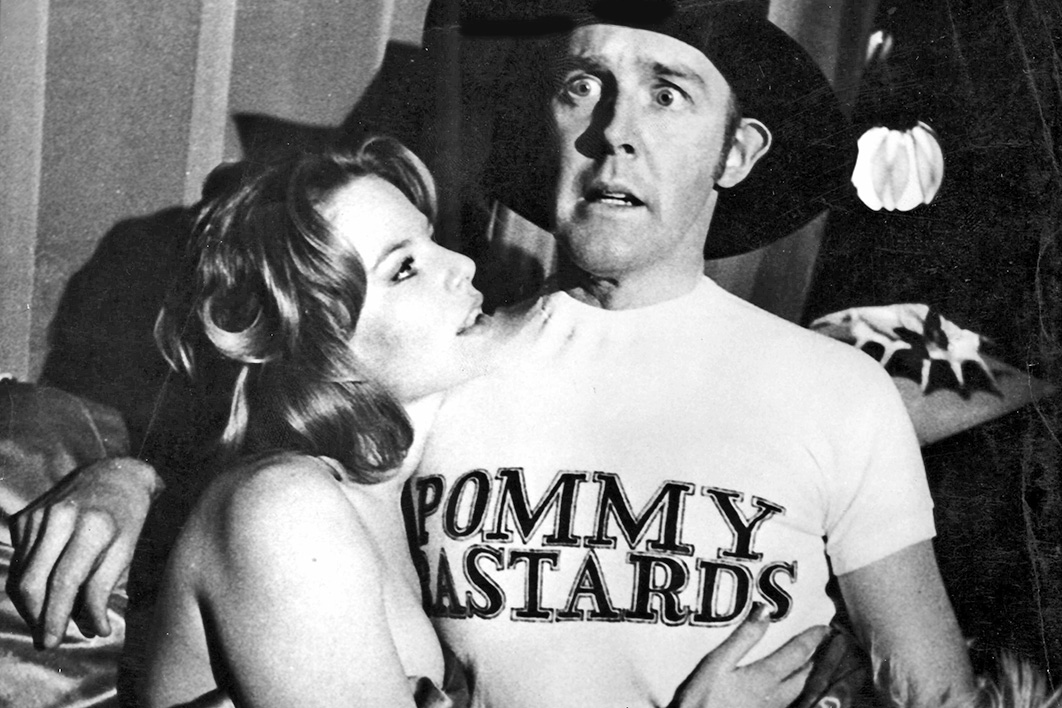

Rooted surveys the most notorious literary censorship cases from the second world war to the 1970s, from Lawson Glassop’s We Were the Rats, Robert Close’s Love Me Sailor and Sumner Locke Elliot’s Rusty Bugles to Alex Buzo’s Norm and Ahmed and the Oz magazine trials. It considers the role of They’re a Weird Mob and the Bazza Mackenzie films in promoting the idea that bad language is an Australian tradition. In this way, Laugesen argues that the use of blasphemy and obscenity are essential Australian freedoms of expression, almost always used in the service of transgression rather than of power, though this view of bad language may conflict with many people’s experience of its use by powerful groups to exclude and intimidate.

Laugesen is at her most original and insightful in the final section of the book, which examines the present proliferation of public obscenity. Here she uses evidence from television and the informal world of social media to measure the shifts in what constitutes offence. She cites the infamous moment on the sixth series of the reality TV show Married at First Sight when Bronson referred to his assigned wife, Ines, as a “cunt.” With scholarly detachment, she summarises responses to the incident, including the journalist James Weir’s playful account of the episode using “cantaloupe” as a substitute. Yet, even here, the context was more interesting than the word. It was clear that Bronson used it habitually, with little sense that it would cause offence. At this moment, the series reached its lowest point, with the “experts” revealed as hypocrites pretending to be superior to the vulgarities of the show they presented.

The masses of spoken-language evidence now available through social media and reality TV may well overwhelm the dictionary-makers of the future, but Laugesen responds with liveliness to this proliferation of evidence. Though she remains cautious about racial terms, she does acknowledge that there may be a link between verbal and physical abuse.

While I was writing this review, Van Badham posted her observation that “fugly slut” was a term of abuse that every woman who makes a public statement online would find among the comments of trolls. For relief from this nastiness, I hope that researchers at the Australian National Dictionary Centre allow themselves some episodes of Gogglebox, in which earthy jokes and innuendo are supplemented by many cries of “Oh my God!” and convivial, beeped “fucks” as families demonstrate that it’s not so much the words themselves that matter but their comic potential and the speaker’s awareness of who is listening. •