The last time I saw my friend Amirah Inglis, eighteen months ago, she had no memory of me at all. Another friend had warned this might be the case, but I didn’t believe her. She wasn’t as close to Amirah as I’d been, I assured myself. Our friendship mightn’t have been as longstanding as others of Amirah’s, but it did go back quite a way, and it was strong.

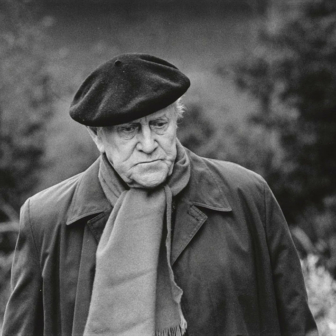

After I moved to Canada at the end of 1998, I stayed with Amirah and her husband, the historian Ken Inglis, during a trip back to Australia while making arrangements to sell my house in Canberra. When my husband and I returned to Australia to set up house in Sydney, we saw them again. Soon after that, the Inglises sold their house and went to Melbourne, no mean feat for a couple in their late seventies, especially considering their many years in Canberra. But Melbourne was where they had come from, and they went back there to be closer to their children and grandchildren. I stayed with them not long after their return. They took me on a tram to Federation Square, and on another day we went in the rain to see a Sidney Nolan exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria.

These were my most recent memories when, in November 2013, my husband and I took a Canadian friend to Melbourne. By that time Amirah and Ken had moved to an apartment in an independent living complex in North Carlton. They had a panoramic view of the city’s northern suburbs and a restaurant downstairs if they didn’t want to bother cooking. With Ken’s daughter Louise, they went to a great deal of trouble with a lunch for the three of us, as well as my son Sam, who was living in Melbourne by then and hoping to take up postgraduate studies in history. For Sam, who had grown up around him, so to speak, Ken was a major inspiration.

And it was true: Amirah had no recollection of me. In spite of the warnings (Ken had cautioned me too), it was a shock. She was very open about it, even in a good humour, and this is because she anticipated another story. This, I soon saw, was how she dealt with the erasure of remembrances. Now she would hear our story, the things we used to do together, how close we were, the passions we shared and the laughter and outrage that accompanied them, and I would be its reasonably reliable narrator.

So I began with how we first met in 1975 when I was having dinner with a neighbour of hers in Canberra and she dropped in for coffee. This was when she and Ken had just returned from New Guinea, where he had been vice-chancellor of the University of Papua New Guinea in Port Moresby and she had written “Not a White Woman Safe”: Sexual Anxiety and Politics in Port Moresby, 1920–34, the first of the five books she wrote (she edited two others). In PNG, she had also lectured at the Administrative College, thanks to the liberal-minded principal David Chenoweth, and conducted her own English classes for university and college labourers, one of whom, Kauage, went on to become the most eminent of PNG artists.

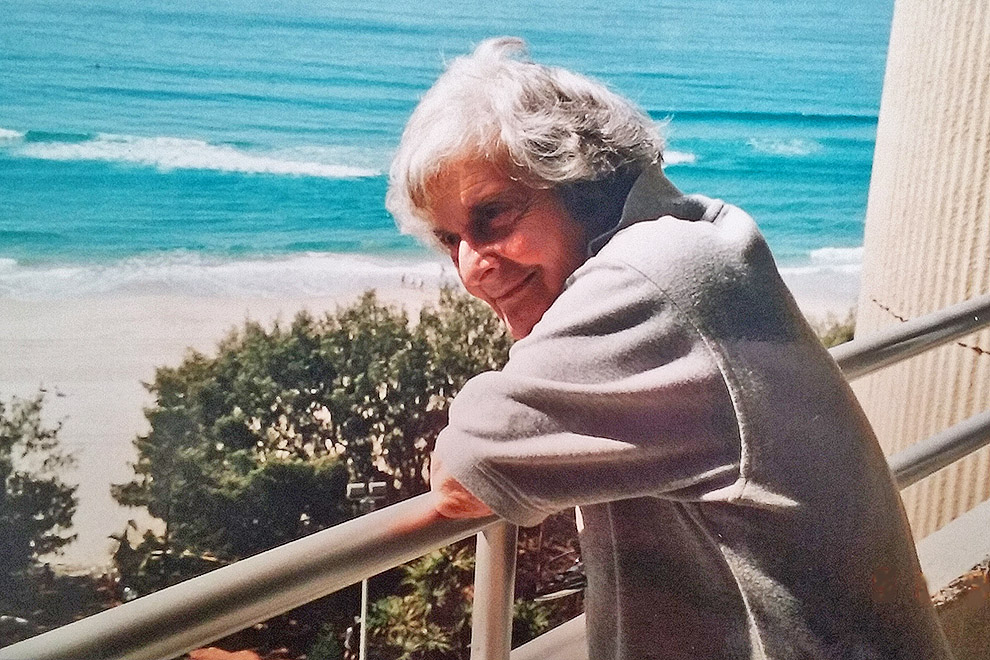

Oddly, I took her that first time to be unapproachable – she, the warmest of women. Her looks were certainly striking, which may have contributed to my wide-of-the-mark impression. Her short hair was black, with one broad streak of white in it; she later divulged it was dyed, but however it had come about it produced the desired effect. What also impressed was her voice: low and authoritative, with a faintly judgemental tone in it (so quick was I to judge). Her dark eyes were sparkling and inquisitive. It was only later that I came to know her marvellous laughter, and the joy she took in so many aspects of life.

We became close in the 1980s. We were both members of the infamously bolshie Black Mountain branch of the Labor Party, and both of us were congratulated in its newsletter for publishing books, in my case my novel West Block, in hers the first volume of her memoir, Amirah: An Un-Australian Childhood, which described her arrival in Australia (as Amirah Gutstadt) in 1929 and her childhood years in Melbourne. We were in a couple of yoga classes and at some stage we began to go swimming together. But I think the two things that cemented the friendship were our Jewish, communist backgrounds and our computers. The former needs little explanation, but I feel I should say something about the computers. Computers for personal use were coming on the market then, but they were crude apparatuses compared with what’s available today. Few of us knew very much about them, how they worked and, more importantly for our purposes, how to make them work. Ken and Amirah had bought an Osborne, and knowing no better I followed suit. They were clunky, maddeningly unbiddable machines, and as ugly as sin. Compatibility between brands was on the far horizon, and none of us knew of the internet. The printers too were bulky and ridiculously temperamental. Eventually Amirah bought a Toshiba and I got my first Mac, but there was a lot of frustration, feverish consultation and laughs in the meantime.

More books followed – Australians in the Spanish Civil War and a second volume of autobiography, The Hammer & Sickle and the Washing Up, her second book, Karo: The Life and Fate of a Papuan, having appeared in 1982 – and she also contributed articles and reviews to magazines and journals including Overland and Australian Society.

In the mid 1990s Amirah, Penny Pollitt, Brigid Cole-Adams and I met for lunch every other week to discuss matters of interest to us all, mainly political. Amirah had had a brush with breast cancer and we saw our regular get-togethers as a means of accelerating her recovery, which proceeded well, though I doubt we were the cause. A few years later I interviewed Amirah for the National Library, and the four tapes covering her life now form part of its oral history archives. The interview took place in the year I left for Canada and the Inglises kindly offered to look after a huge portrait of me until I came back. When I did return, the portrait was still hanging in the hallway, and Amirah was still playing the piano, still taking long walks with Ken through the streets of northern Canberra, still working in her garden, and still struggling with Sudoku. I had little inkling then why she persisted with it, though she did mention trouble with her memory. Everybody has trouble with memory, I thought. But some, alas, quite a bit more than others.

Amirah died at 5.25 on the morning of 2 May, almost eighteen months to the day after I began telling our story for her. This is why I am writing this, out of my love and, again, my shock. All told, hers was an eventful, satisfying, happy and, at eighty-eight, a reasonably long life. But a death is a death, and I can’t quite believe she has finally gone from us. Nor, I am aware, can so many others.

Sadly, it’s been a season of dying, a slow dance rapidly picking up speed. Its onset seems to have been Gough Whitlam’s death in October, followed in March by Malcolm Fraser’s. These were the big names, the giants of an era, signifying perhaps more than anything that era’s passing. Not long before Fraser’s, Mavis Robertson, erstwhile communist, women’s liberationist and pioneer of the industry super funds, had died too; and soon after that came the death of Pat Eatock, the feminist and Aboriginal activist instrumental in the successful legal challenge to Andrew Bolt’s outrageous contentions about fair-skinned Aborigines like her.

All of these wonderful people played their part in my life, some more than others, but none quite so much as Amirah. Sharp, warm, comforting, consoling, immeasurably funny, deeply concerned about the state of the world and committed to the people she shared it with; as long as I retain my memory, this is the woman who will linger there. For the moment, however: vale, my friend. •

Read an extract from Amirah: An Un-Australian Childhood here