The modern usage of the seemingly ubiquitous phrase “culture wars” first appeared in sociologist James Davison Hunter’s Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America, published almost thirty years ago in 1991. Hunter thought American politics was marked by several polarising “hot button” issues — abortion, gun control, recreational drug use and homosexuality — and that people who held a certain opinion on one of these issues were increasingly agreeing on the others.

The term was picked up by Pat Buchanan at the following year’s Republican convention. Buchanan, a prominent conservative commentator, had worked for Republican presidents Nixon, Ford and Reagan and was now on a quixotic quest to become the party’s presidential candidate. (He was certain to fail: the Republicans were always going to nominate incumbent president George H.W. Bush.) He was the standard-bearer for those right-wing Republicans who thought Bush was too moderate.

Buchanan’s convention speech gained enormous, mainly critical, attention. “There is a religious war going on in our country for the soul of America,” he said. It was “a cultural war, as critical to the kind of nation we will one day be as the cold war itself.” He derided the things he believed Bill and Hillary Clinton would impose on America: abortion on demand, homosexual rights, discrimination against religious schools, women in combat units.

In some ways, the timing is strange. The early 1990s should have been a period of celebration in the United States. The cold war had ended with the collapse of Soviet power; America had recently achieved a quick and relatively painless victory over Saddam Hussein’s Iraq after it had invaded neighbouring Kuwait. But discontent was palpable on the right.

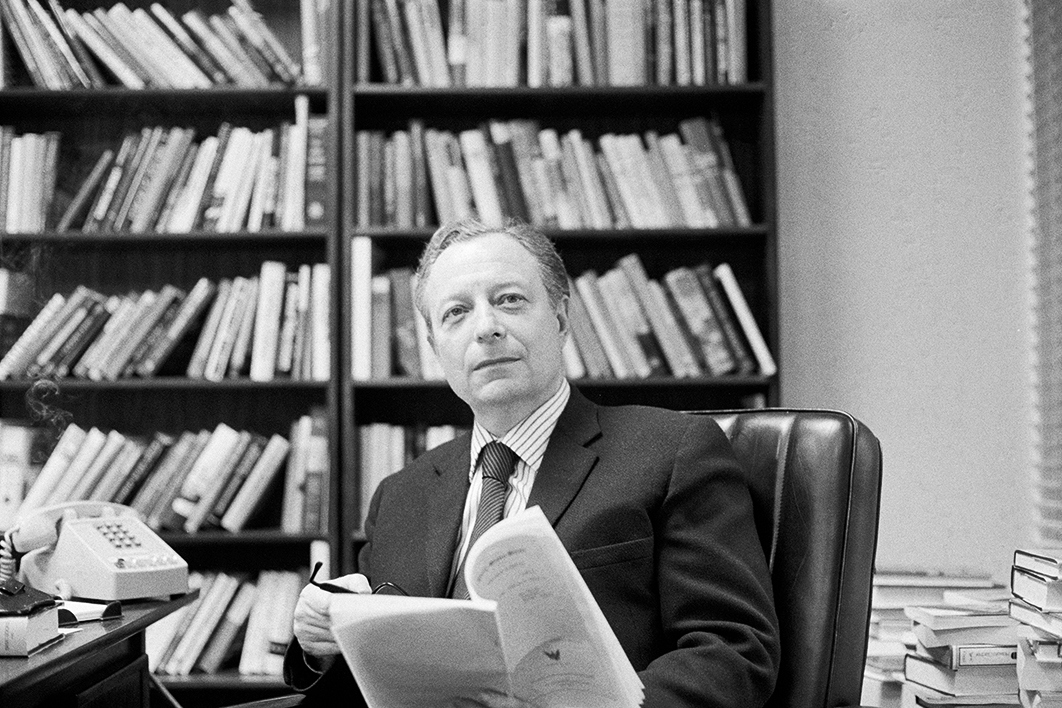

Among the most articulate figures during that period was Irving Kristol — known as the godfather of neoconservatism — who added a domestic dimension to the neoconservatives’ traditional foreign-policy preoccupations. “There is no ‘after the cold war’ for me,” he said in a speech in East Berlin in 1993. “My cold war has increased in intensity, as sector after sector of American life has been ruthlessly corrupted by the liberal ethos.” He was increasingly concerned by “the clear signs of rot and decadence germinating within American society — a rot and decadence that was… the actual agenda of contemporary liberalism.” One war had given way to another, even more challenging: “Now that the other ‘cold war’ is over, the real cold war has begun.”

This rhetorical slippage between internal and external — between authoritarian enemies and democratic competitors, neither of which should be given any quarter — was central to the emerging “war.” It was seen again with the emergence of the Tea Party in 2009, the first year of the Obama presidency. This group of populist Republicans called on “American patriots” to “take back” their country. The movement took its name from the famous incident in the lead-up to the American war of independence summed up by the slogan “no taxation without representation”; but they ignored the fact that their modern-day targets were not colonial oppressors but their fellow citizens and their own democratically elected government. Just as Republican vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin had celebrated the “real America” during the previous year’s campaign, the implication of the Tea Party’s rhetoric was that some parts of America, and some citizens, were less American than others.

Many of the Tea Party’s views filtered across the Pacific. But not all: Australian culture warriors were much less likely to focus on abortion or the right to own guns, and Australia’s early “culture wars” seem to have been more explicitly religious than political. In fact, the first Australian to use the term to describe local developments appears to have been George Pell, who was bishop of Melbourne at the time. In a speech at the University of New South Wales in November 1995, Pell declared that the threat of communism had given way to the “culture wars,” a struggle over “the redefinition of what is good and what is evil.” This clash between “Judaeo-Christianity and the new paganism” was a battle to resist “the culture of death” and “the soft nihilism which has settled over the English-speaking world.”

Kristol and Pell weren’t alone in using highly charged language to attack their opponents and rally their supporters. Over the three decades their fellow warriors have assembled a highly effective rhetorical armoury.

It’s probably no coincidence that their best-known phrase, “politically correct,” dates from around the same time as the declaration of the culture wars. According to Proquest, a digital database of US magazines and newspapers, the phrase rarely appeared before 1990. Then, in 1990, it appeared more than 700 times, and in 1991 the figure jumped to 2500. Donald Trump made frequent use of it during the 2016 presidential campaign. When journalist Megyn Kelly questioned him about his references to women he didn’t like as “fat pigs,” “slobs” and “disgusting animals,” he replied, “I think the big problem this country has is being politically correct,” drawing applause from his supporters in the audience.

Much more recent are two related terms. The first, “virtue signalling,” gained its current popularity after an article in the Spectator in 2015. It refers to the conspicuous expression of a moral stance, especially one that doesn’t require any action or cost anything to the person making it. Any statement of a moral position — left, right or otherwise — is a potential target, but it is usually directed at expressions of progressive attitudes.

The second, “woke,” is the vogue new word among culture warriors. Like “politically correct,” it is a classic case of flipping, taking a word and turning it back on the group that originally used it. Originally woke was part of the vocabulary of black Americans: “stay woke” meant staying sensitive to issues of racial justice. But in the last couple of years it has become a term for denouncing those who are hypersensitive to racial slights and other such issues. Actor Laurence Fox has said he won’t date woke women, right-wing journalist Toby Young declared Fox was “terrorising the wokerati — and it’s brilliant,” and the London Sun branded Harry and Meghan “the oppressive King and Queen of Woke.” Not to be outdone, Miranda Devine branded the New York Times a “woke citadel of militant secularism.”

Interestingly, in the early manoeuvring for the Democratic presidential nomination last year, Barack Obama called out young Democratic activists for being woke. He was criticising the use of social media to focus on bad things candidates have done or said in the past. For Obama, this hypercritical and unforgiving practice was effectively a politics of exclusion that cut across building broader movements.

Activists on the left can be intemperate in their use of language, and can certainly contribute to the aggressive waging of political controversies. But while the left were active on individual issues, and not always courteously so, they haven’t formulated their efforts as a “war for the soul of America” or a struggle against “the culture of death.”

Although “culture wars” has become a cliché, we shouldn’t forget what a strange and ambiguous juxtaposition of words it is. The key is in its ostentatious militancy, which lends itself to heroic (and sometimes unintentionally comical) posturing. Before he became a Liberal MP, Tim Wilson declared that he was “so hardline against the nanny state” because he would “rather die on my feet than live on my knees.”

Culture warriors thrive on polarisation, and on the uninhibited denunciation of views they disagree with. The attacks on political correctness, virtue signalling and wokeness share two essential characteristics: they are expressions of denigration, and they are inherently imprecise. Like beauty, political correctness is in the eye of the beholder, but the imprecision doesn’t reduce the vehemence with which the weapons are used. Rather the reverse, in fact.

Sometimes this is abetted by the old tabloid trick of substituting labels for description, as the ever-helpful Graham Richardson did in a column for the Australian headlined “Labor Must Let Go of Left Lunacy.” Who could disagree? Another key to uninhibited denunciation is choosing generalised and typically anonymous targets: leftists, eco-catastrophists and thought police, for example, with adjectives to suit: extremist, utopian, militant.

When we move from labels to explanation, the imagination can run even more wildly, as Miranda Devine’s did when she wrote a column last October headed, “Eco Madness May Be Reason for Disastrous Boeing 737 MAX Safety Issues.” “No one has said explicitly yet,” she confided, “but this relentless pressure to reduce emissions appears to have been a significant factor in the disastrous safety failures… which resulted in two fatal crashes in the past year claiming 346 lives.” It was the eco-catastrophists’ fault for “appeasing the climate gods” in forcing Boeing to try to lower fuel consumption in its new series of aircraft by introducing what proved to be fatal problems. No one was surprised when Devine blamed greenies for this summer’s bushfires.

It is a curiously asymmetrical “war.” Cultural warriors of the right are much more visible and vocal than their presumed adversaries. They have entrenched beachheads in the media. In turn, they charge that left-wing influence is dominant in universities, the national broadcaster and even the media in general, and they are ever vigilant for examples to attack. But institutions like these have far more quality controls than any faced by Murdoch columnists like Devine. Some media and some journalists have reacted to the fragmentation of the industry by affirming the prejudices of their core (aged) readership and provoking attention-getting outrage among other readers.

The clearest expression of this sectarian media is Murdoch’s Fox News. Although cultural warriors typically decry the “identity politics” of others, such as women or gays, their own identity is central. Fox News is always on the lookout for anti-white “racism” and discrimination against men. (Pat Buchanan’s 2011 book, Suicide of a Superpower, included a chapter titled “The End of White America.”)

In 2012, Fox’s top-rating program, The O’Reilly Factor, gave three times as much airtime to the “war on Christmas” as it did to the actual wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Libya and Gaza combined. Seven years later, after flare-ups each year, the network was heatedly debating the question “Christmas tree versus holiday tree?” as Donald Trump’s impeachment loomed. Late last year the imaginary “war on Thanksgiving” became another Fox bugbear.

While there is a market logic to using these cultural wars to attract and retain a committed audience, a different logic faces politicians seeking majority support. But it is possible to wage cultural war — and so cater to the party base — without adverse electoral consequences. In Australia, the Howard government education minister, Julie Bishop, bolstered her call for a national curriculum with the claim that state governments had hijacked school subjects, in some cases adopting themes “straight from Chairman Mao.” Did she really believe this?

Views like Bishop’s didn’t translate into effective policy — in fact, it was a Labor government that ended up creating a national curriculum — which points to another strange characteristic of culture warfare: substantive victories don’t seem to be the point. It’s the battle that matters, and the extent to which it dominates public debate. Occasionally, real policy initiatives have been launched, notably the attempt to abolish section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act (which was seen as a threat to free speech) and the current efforts to introduce a freedom of religion act. But in each case the fight seemed more important than the outcome.

In their thirtieth year, the culture wars show no sign of abating. Their greatest impact, and one that will probably persist, is on the political environment rather than the policy agenda. Culture wars have made politics more polarised and coarsened political debate. Rather than argue over evidence, their proponents attack the bona fides of those putting the argument, and there is less weighing of evidence and respect for expertise in political controversies. Somehow, faced with enormous challenges like climate change, we need to recover a democratic politics that is less like war and more like negotiation. •