After a long Melbourne winter, spending time in a place like Ouvea — one of four atolls that make up New Caledonia’s outlying Loyalty Islands — can be dangerous. Its long, sandy beach and blue lagoon resemble the ultimate tourist clichés, and the risk of sunburn increases every day when the ocean is just metres from your door.

Despite the idyllic scenery, Ouvea carries a tragic burden of history. New Caledonia’s referendum on self-determination, which takes place on 4 November, is the culmination of a twenty-year decolonisation process that began with the Noumea Accord, an agreement between the French state and local parties signed on 5 May 1998. That was the tenth anniversary of a crisis — the 1988 Ouvea massacre — that almost tipped the country into civil war. The polarisation of those days, though muted today, still echoes through political debates.

The overwhelming majority of Ouvea province’s population is indigenous Kanak, and members of independence parties have dominated nearly every provincial government over the past thirty years. But they preside over a declining population. With limited employment available on the island, some working-age people seek education, employment or enjoyment on the main island of Grand Terre. At the last census, in 2014, only 3374 people were living on Ouvea.

According to Benjamin Malie, principal of the Guillaume Douare junior secondary college, the lack of a senior high school on Ouvea contributes to the outflow of locals. “We don’t have a lycée on Ouvea, so many families move to Grande Terre to assist their children complete schooling,” he told me. “After they’ve finished, however, some of them don’t return, so many people from Ouvea are still living in the capital, Noumea, or other towns on the mainland. Our college has dropped from 200 pupils to just eighty-nine this year, and the Protestant and public schools have also seen reductions.”

Ouvea’s food and water security is threatened by a changing environment. The reef still teems with marine life, but on the ocean side of the island, near Saint Joseph, the effects of coastal erosion can clearly be seen. Local authorities are focused on dealing with the immediate effects of climate change on water and food; three desalination plants operate, and tankers deliver fresh water to homes and schools at times of water stress.

Despite these constraints, local authorities are working to create a sustainable model of development for the island and trying to overcome the challenges of expensive transport and communications, with a new wharf and warehouse welcoming three boats a week delivering supplies.

Like most outlying islands across the region, the pace here is different from the hassle of the capital. Beyond their beauty, Ouvea’s beaches are a crucial economic resource, acting as a drawcard for overseas and domestic tourists. In recent years, there’s been a particular emphasis on small-scale tourism, with gites (bungalows) established in Kanak tribes to tap the ecotourist market. The provincial government seeks to lure Noumea-based public servants looking for a beach escape during the school holidays. Locals run a range of small businesses, promoting walking tours, fishing and boating.

But New Caledonia’s economy essentially relies on the extravagant wages and bonuses paid to French public servants and the “value-adding” on imports by local business elites. Backpackers in the Loyalty Islands will find that the beer is more expensive than in independent Vanuatu or Fiji.

Even when you focus on Ouvea’s economic future, however, it’s hard to avoid traces of the past.

Driving along the island’s main road, you pass the tall green fence, topped with barbed wire, of the police station in Fayaoue. At nearby Hwadrilla, there is a roadside memorial to “the nineteen,” the Kanak martyrs of 1988. In the northern tribe of Gossanah, the old building for the École Populaire Kanak (Kanak community school) is festooned with banners calling for non-participation in this year’s referendum, an echo of the boycott of New Caledonia’s last failed referendum in 1987.

Next to the sporting field at Gossanah is the gravesite of Djubelli Wea, an independence leader from Gossanah, with a plaque that pays homage to three Kanak leaders who died in 1989, and to the reconciliation that followed: “To all generations to come — remember that on the night of 4 May 1989, blood was spilt on Ouvea. Pardon — Haiömonu me ûsoköu.”

Much as people have reconciled since the armed conflict of the 1980s, it’s impossible to understand the present without remembering the past. Next month’s referendum is the culmination of a twenty-year transition under the Noumea Accord, an agreement signed by the French state, the independence movement Front de Libération Nationale Kanak et Socialiste, or FLNKS, and anti-independence politicians led by Jacques Lafleur.

In 1987, in the midst of the French army’s militarisation of New Caledonia, the FLNKS boycotted a referendum organised by France that purported to determine the future of the country. Despite an overwhelming Yes vote to stay with France, the referendum was meaningless without the participation of the colonised Kanak people.

The following year, Jean-Marie Tjibaou and the FLNKS leadership called for a boycott of the French presidential elections, in which conservative prime minister Jacques Chirac was challenging the incumbent Socialist Party president François Mitterrand. During the FLNKS protests, a group of Kanak independence activists led by Alphonse Dianou attempted to raise the flag of Kanaky over the police station at Fayaoue. In the subsequent melee, three gendarmes were killed and another mortally wounded. Twenty-seven others were taken hostage and hidden in caves in the north of the island, near the Kanak villages of Gossanah and Takedji.

The Ouvea crisis led to a major military mobilisation on the island. Villagers were mistreated and even tortured by French troops trying to find the hostages. The assault on the caves to free the captured police coincided with a final (and unsuccessful) attempt by Chirac to glean votes to win support before the second round of the presidential elections. On 5 May 1988, his government abandoned negotiations and elite police and an army commando unit stormed the cave. Nineteen Kanak activists were killed, with at least three executed after surrendering. Dianou was shot in the knee, and left to die.

The Ouvea tragedy made all parties step back from the brink. France’s incoming prime minister, Michel Rocard, proposed negotiations. The subsequent Matignon and Oudinot Accords, sealed by a handshake between FLNKS leader Jean-Marie Tjibaou and anti-independence leader Jacques Lafleur, provided for amnesties for crimes committed before August 1988.

The legacy of grief and division contributed to the assassination of Tjibaou and fellow Kanak leader Yeiwene Yeiwene the following year. They had come to the island on 4 May 1989 to mark la levée du deuil, the end of a year-long period of mourning for the nineteen. At the ceremony, Tjibaou and Yeiwene were shot and killed by Djubelli Wea, who was immediately gunned down by Tjibaou’s bodyguard.

It took a decade and a half to reconcile the families, clans and supporters of these dead. Led by customary chiefs, priests and pastors from the Protestant and Catholic churches, this cultural process of reconciliation and pardon has been vital in sealing a breach that could not be healed by judicial mechanisms.

One person who seems keenly aware of the continuing sensitivities is French president Emmanuel Macron, who visited New Caledonia in May this year, and included Ouvea on his itinerary. For the first time, a French president tried to pay homage at the memorial to the nineteen Kanaks killed by the French army.

At his home among the Kanak tribe of Gossanah, Djubelli Wea’s brother, Maki, tells me there was local opposition to Macron’s visit. Because of this, the French president left Ouvea without placing a wreath on the memorial at Hwadrilla. “They announced Macron’s arrival here without contacting the customary chiefs on the island, without contacting the families of the victims,” he says. “The FLNKS announced it in the media, but the people of Gossanah were surprised and we raised our finger to all the people over there.”

For the first time in thirty years, the people of Gossanah didn’t place flowers on the graves of the nineteen on the anniversary, he says. “The high commissioner even lobbied us over Macron’s visit. But we didn’t cede ground — we’re not like the people of the FLNKS who give in.”

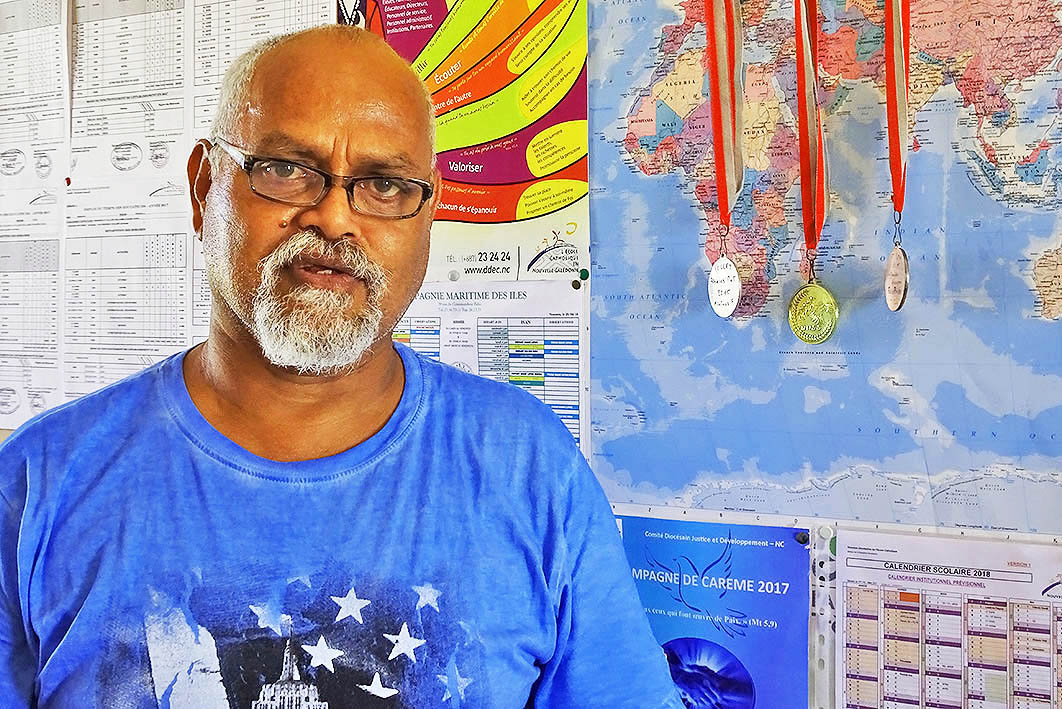

“We say no”: Maki Wea of the Kanak tribe of Gossanah. Nic Maclellan

Meanwhile, like other low-lying atolls around the Pacific, Maki Wea continues to advocate for Kanak Socialist Independence, the guiding slogan of the 1980s. Since July, he has been speaking out in public, calling for non-participation in this year’s referendum, both as a member of the small Parti Travailliste (or Labour Party) and also as “a child of Gossanah.”

“Today, I can’t just act like an old man, working in the gardens, without saying something, because I think of the next generations, the sons of my sons and their sons after them. For they will ask, ‘Papa, what did you do when the French state and the local right-wing parties and the leaders of the FLNKS moved away from the objective for which so many have sacrificed their lives — the goal of indépendance Kanak et socialiste?’”

He criticised those independence groups on Ouvea who campaign for a Yes vote on self-determination within France: “There are plenty of fine speeches out there: ‘Vote Yes, to remember those who died for independence.’ But we say no, this referendum is just neo-colonialism.”

As I was hitchhiking up the forty-six kilometre road that runs along the spine of the island, a young man stopped to offer a lift. We talked about fishing and Australia and the weather, and then drifted on to politics.

“I’m part of the generation who grew up after les évènements,” he told me. “So thinking about independence is different for me compared to my parents. We look differently at the referendum and I have questions about what it means.” Does that mean he will vote No or stay at home on 4 November? “Oh no, I’m voting Yes, for independence. But we have to build this independence. We have to be involved to make it happen.”

For the first time since 1958, the looming referendum poses a clear option — whether to stay within the French republic or leave as a sovereign nation. New Caledonians will vote on the question: “Do you want New Caledonia to accede to full sovereignty and become independent?”

Some people may go fishing on 4 November, but Wea’s call for non-participation is not accepted by most independence supporters on the island. Activists from the largest independence parties, Union Calédonienne and the Parti de Libération Kanak, have been out for weeks, seeking to mobilise people to turn out on the day. At the last provincial elections in 2014, only 65.2 per cent of eligible residents of Ouvea went to vote, so the FLNKS is seeking to boost numbers, organising community meetings to explain the significance of this year’s decision.

One quiet night, I joined a small team of activists at Hulup, near Ouvea’s airstrip. In a local community hall, twenty-five people had gathered to hear a presentation about the referendum, followed by discussion on reasons to vote (and to vote Yes).

The FLNKS has produced a short film highlighting the economic and political milestones achieved by the independence movement since the mid 1970s (such as the 51 per cent local control of the Koniambo nickel smelter in the Northern Province, an unprecedented example of engagement with a transnational resource corporation in Melanesia).

Then there’s a PowerPoint presentation setting out the FLNKS vision of a sovereign Kanaky–New Caledonia, with the current Congress transformed into a national assembly and an elected president replacing the French high commissioner. There’s also a presentation about public finances and budgetary options for an independent state, an attempt to calm fears that a Yes vote will lead to Paris turning off the financial taps.

And then there are questions and sharp comment, with a wide-ranging discussion over what independence might mean. Much of the discussion is in the local languages of Iaai and Fagauvea, leaving your correspondent adrift, but the tone of one woman’s voice suggested that the FLNKS activists have some questions to answer about who will pay for her pension.

Ouvea’s deputy mayor, Robert Ismael, talks of the potential to give greater capacity to the local municipal council, if the Article 27 powers are transferred from Paris to Noumea (currently, New Caledonia’s provincial assemblies and local Congress come under the authority of the government in Noumea, but the communs, or municipal councils, are still controlled and financed as French state institutions).

Ismael also cites the possibility of extending development partnerships with Australia, New Zealand and neighbouring Melanesian countries, along the lines of the municipality’s current engagement with health authorities from Vanuatu. “We need to decolonise our heads and be proud like Vanuatu,” he declares.

With just a week to go before 4 November, time is running out for mobilising Ouvea’s 4351 registered voters — some on the island and some planning to use “delocalised” voting booths in Noumea. Local activists are planning a final festival on the island to promote a Yes vote, and will then join a major national rally in the capital, organised by the FLNKS at Ko We Kara on 30 October. •