The weariness over Covid-19 seems palpable. People just want it all to be over. And policy fatigue is beginning to parallel the physical fatigue that is one of the long-lasting sequelae of Covid-19 infection. Fatigue ripens the temptation to indulge in magical thinking, but the hope that Australia might be spared spikes in infections has been dashed by a week of double-digit rises in the number of new cases from community transmission in Victoria.

Six months into this pandemic and some patterns are becoming clear. For countries that have taken a strong containment-and-control approach and were able to catch the epidemic early — like Australia but also like China and South Korea — the daily count of new cases has come down from its initial peak, but relatively small upsurges have been occurring as new clusters of infection come to light. This pattern speaks to the virulence of SARS-CoV-2 — any amount of active virus, no matter how small, will break out at an exponential rate.

In a handful of countries, rates have been brought down to close to zero, and these are touted as places where elimination may be possible. New Zealand and Iceland are the prime examples, both having the advantage of being an island with a relatively small population. But even when numbers have reached zero, new cases have appeared, albeit attributed to arrivals from overseas.

The press briefings delivered by the World Health Organization on a near-daily basis since the end of January have been remarkable for their accuracy and consistency across a rapidly evolving pandemic. One of the very few cases where a correction was issued came after Maria Van Kerkhove, technical lead at these events, remarked on 8 June that transmission from asymptomatic individuals seemed rare. Her remark was seized on by the world’s media and interpreted as a reassuring signal that the majority of cases of Covid-19, which are asymptomatic, would not be able to transmit the virus onwards. The WHO quickly walked back that interpretation, making a distinction between those who are truly asymptomatic and will never go on to develop signs of illness, and those who are simply pre-symptomatic.

In fact, it seems that one of the keys to the virulent spread of SARS-CoV-2 is that its infectiousness is greatest a couple of days before symptoms appear. There is a relationship between viral load and both the likelihood of developing symptoms and the likelihood of transmitting the virus to others, but the extent of transmission from those with a low but not non-existent viral load is not entirely clear. The issue is important, because it goes to the question of elimination. If people who are asymptomatic and will never go on to develop illness can nevertheless transmit virus, even if rarely, then true elimination becomes massively difficult, short of testing the whole population on a regular basis.

In practical terms, there may be little difference between tight control and elimination strategies. The control strategies adopted by Australia and many East Asian countries depend on finding active cases and immediately implementing the isolation, quarantine and contact-tracing strategies needed to contain them. If this isn’t done, we now know that exponential spread will be inevitable.

In 2011 a previous pandemic, HIV, yielded a new term in the public health lexicon, “virtual elimination.” The example was the elimination of the transmission of HIV from mother to child: in the absence of any treatment, around a third of infants born to mothers living with HIV would become infected either prenatally, from blood contact during the birth itself, or postnatally through breast milk. But suppressing the mother’s viral load through effective antiretroviral therapy could bring this risk down to nearly zero.

In practice, of course, it was an enormous challenge to ensure that all mothers with HIV not only were diagnosed but were also given access to and used effective antiretroviral therapy. The global resolve to overcome these challenges meant that the goal of virtual elimination — defined as fewer than fifty transmissions per 100,000 births and a transmission rate of under 5 per cent — was seriously pursued.

Back in early April, the Grattan Institute was arguing that Australia should set itself the goal of total elimination of Covid-19. Only with total elimination, it said, could physical distancing be abandoned and full economic activity resumed. What we have learnt since then, not only from Australian experience but also particularly from China, suggests that virtual elimination may be more realistic. Precise criteria would need to be developed, and would include working towards zero levels of community transmission monitored by a mix of sentinel surveillance (random testing of slices of the population), location-specific quarantine when outbreaks appeared, and the mainstays of isolation and contact tracing.

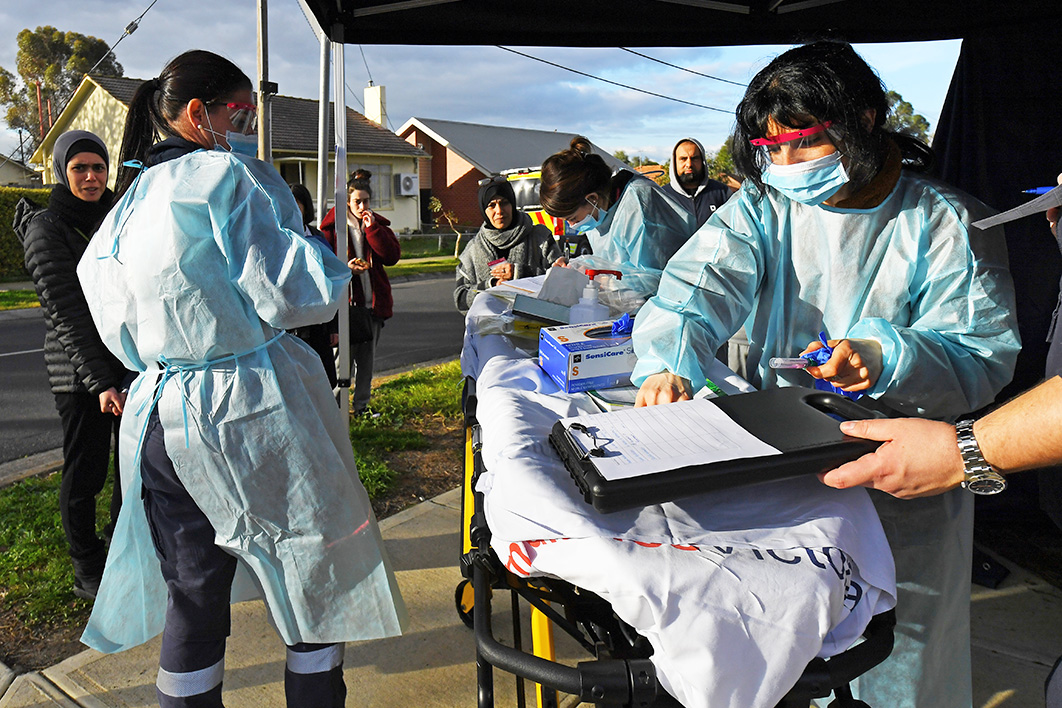

The current Victorian upsurge has exposed some of the limitations of both state and national strategies. Any criticism seems churlish when Australia’s situation is compared with the constant news of the unmitigated disasters in the United States and Britain, but, even so, improvements can be made. In particular, the highly centralised Victorian response has given authorities there little flexibility to respond to changing conditions. Neither local hospitals nor local government are informed about the location of new cases as they are identified. Every positive case has a case management team assigned and cases are notified centrally, from where contact tracing is managed, but this leaves little capacity to develop a sense of local control of emerging cases. The lack of mutual commitment at the local level will make it much harder to introduce the local lockdowns that would seem to be necessary to manage outbreaks.

In the same way, public advice has been anodyne and not designed to foster active and ongoing commitment to control measures. In effect, the message from government, federal and state, has been “Trust us, we will find all cases and eliminate the threat. Go about your business normally.” This is the implicit message of the COVIDSafe app and the “snapback” slogans. A much more robust strategy would involve building mutuality into the response, with citizen action serving as a sign of social solidarity.

This is the real significance of the debate about mask wearing. Face masks undoubtedly contribute to slowing the spread of Covid-19, and the federal government’s reluctance to advocate, much less mandate, their use amounts to telling its citizens it has the problem under control, rather in the tradition of former Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s catchphrase, “Don’t you worry about that.”

Although its situation is very different from Australia’s, South Africa has been among the better responders to SARS-CoV-2. It has provided a very good example with its recent advice to citizens, developed by a collective of experts and based on the science of distancing, patterns of dispersion and amounts of exposure or dose needed for infection to occur. A range of practical tips are provided: as far as possible meet and conduct business outdoors, open windows, wear masks, keep one or two metres from others, avoid crowded spaces.

The key to harm-reduction measures is that they take the world as it is and reduce risk, rather than making impossible demands. The science is still unclear about how much transmission takes place from touching surfaces, for instance, or the extent to which the virus can float long distances in the air. But we do know that the risk attached to hugging and kissing is vastly higher than that of touching a banister, and spending a prolonged period in a closed room with someone else is orders of magnitude more likely to cause transmission than going to a physically distanced supermarket. And while touching your nose or face may provide a route of access for the virus, there is little point in telling people to avoid an almost constant unconscious action.

Quite rightly, Victorian health authorities have been reluctant to call the current spike a second wave of the epidemic. Waves are a way of describing long-term patterns involving thousands of cases — in many ways Australia has not even seen a first wave yet. But spikes, outbreaks and lockdowns are all terms with which we will need to become familiar. As Australia pursues the path to virtual elimination, and if we are not to succumb to an overwhelming fatigue, the most urgent priority is far more active citizen engagement than we have seen to date. •