Subtle Moments: Scenes on a Life’s Journey

By Bruce Grant | Monash University Publishing | $34.95

Australia is an old country and a new nation. A single life could track much that has happened here since the Commonwealth was born in 1901: how a young nation transformed its British assumptions into Asian aspirations, yet often behaves like an “adolescent on the lookout for whatever might turn up.”

At the age of ninety-two, Bruce Grant has produced a memoir of just such a life – a coming-of-age story of a man and his country. As a journalist, public intellectual, diplomat and novelist, he has been writing this story throughout his life, in newspapers, in ten books of nonfiction and in six novels. He sees his life as “part of an evolving human story from the certainties of what might be called small history, with its national heroes and racial and religious myths, to the uncertainties of big history, with its invitation to contemplate a common humanity and global governance.”

The human story starts on a farm in Western Australia, where young Bruce ran free “in a land without vertical boundaries under a glaring sun and immense sky.” The toughness of the land and shrewdness of his people inoculated him against the lure of Marxism or the dogmas of conservatism: “I was suspicious of utopias that did not take account of the sun and the rain.” Grant’s father “used to explain, in a typically light manner, that I had not been baptised because there was a water shortage that year.”

Grant senior, who had served in the first world war, at Gallipoli and on the Western Front, gave a wry personal twist to the argument that the Australian nation came of age on the battlefields. “His rebellious spirit emerged in his war stories,” writes Grant, “which were so anti-British that I was confused as a child about who Australia was actually fighting at Gallipoli. Poor leadership and strategic errors were faults of the British; humour, camaraderie and bravery were shared by the Turks.”

Success in a statewide exam won Grant a place at Perth Modern School, and he “moved from the space and good humour of a rural community to a combustible world of intellectual rivalry, competitive sport and girls.” Later, as a journalist, he was always willing to argue with his editors about the editorial line (and how they cut his copy). That spirit showed early, when a confrontation with the headmaster saw Grant abandon his final school year. “I decided that I did not wish to be a prefect in his kind of school,” he writes, “let alone its captain.”

Having already written snippets for the Perth afternoon newspaper, the Daily News, Grant was taken on as a reporter. The writing and thinking life began. When the second world war erupted, he put up his age to enlist and commenced a broader education in the ways of the world. Spared war’s peaks, suffering only the lower levels of boredom, he had time to question his crude patriotism and “the hole at the centre of what it was to be Australian.” Why must Australia behave merely as part of the British empire? Why did Australia have no voice in the peak councils of war?

“It was like waiting for rain in a drought; there was nothing you could do except participate in the drought, and wait,” he writes.

The same could be said of war… Australia was not important in world affairs. We were robust, conscientious and courageous, as good as anyone on the fields of sport and battle, but we did not control our destiny, which was determined somewhere in the northern hemisphere. Whatever this condition was called, it was neither right nor fair!

A central motif of his writing life was set: the need for Australia to set its own destiny. “For me, the Australian story contained a persistent contradiction: we had underdog values at home and topdog values abroad. We resisted British cultural mythology at home, with dreams of mateship and a republic, but we accepted an imperial view of the world.”

For Australia, Western supremacy lost its inevitability during that war. “Since then, Australia’s engagement with Asia became more urgent and more real. Asia became less a threat to European supremacy and more a test of Australia’s own competence and intelligence.”

At war’s end, an ex-serviceman’s allowance took Grant to Melbourne University. On graduation, he joined Melbourne’s Age newspaper; he was an experiment, the only university graduate on the staff. He imbibed the lore of “the story,” the entity that became “the news” published by the newspaper. Stories originated in the world of public events but were shaped by the skill and serendipity of reporters, the people who found the “angle” and “wrote up” the yarn, perhaps combining two stories to make something more important than either of the original pair.

Grant sees journalism as a rough-and-tumble profession:

It has certain rules, like getting the facts right, but it is under pressure to reach quick conclusions, because of the nature of news and deadlines. The result is by no means an accurate reflection of a society. So much happens that journalism does not touch. So much that it touches is hurriedly recorded. So much is tainted by commercial or personal bias. Yet, even with this disability, journalism is a vital part of public life.

In 1954, Grant set out to see the world as a foreign correspondent. He spent the next decade in London, Washington and Singapore, developing “ideas about the world and Australia’s place in it that have remained with me.” To see your country clearly, stand outside it.

Big leaders stroll through the pages of Subtle Moments. Of the two US presidents he dealt with, “Kennedy was a man of taste. Johnson a man of appetite. Each reflected aspects of the American experience.” Meeting Kennedy at Harvard several times before he became president, he recalls not charm or charisma but the canniness and caginess of a cautious politician.

Covering the failed 1956 attempt by Robert Menzies to negotiate with Egypt’s president Gamal Nasser during the crisis over control of the Suez Canal, Grant saw an Australia out of its depth:

I went to Cairo to report on Menzies’s mission on behalf of the canal users, and saw his brilliance pegged back, his inability to understand Egypt’s national pride or Nasser’s ambitions made clear. My first sight of the bulky, white-haired Australian prime minister, in his dark, double-breasted suit, wiping his pink brow in the heat, moved me unreasonably.

A few years later, heading to Asia, Grant took letters from Menzies to Australian ambassadors that asked them to give the reporter “some special personal assistance and open a few doors for him. He is to be completely trusted and will, I am sure, not involve you in any embarrassment.” Reflecting on that unusual endorsement of journalist by politician, Grant thinks Menzies “accepted that the challenge of what to make of our location in Asia was a test for us all… He was possibly genuinely interested in what I would make of it all, and thus offered a helping hand.”

When Menzies retired, Grant kept in touch. “We had in common a background as scholarship boys from the country, a liking for literature and a romantic view of leadership.”

Grant is too good a journo, though, not to record a meeting with the man who signed the ANZUS treaty, the US Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, who referred to Australia’s longest-serving PM as “that fat fraud, Bob Menzies.” Good quotes are always gold, even if you have to hang on to them for decades before use.

In 1964, Grant resigned as the Age’s Washington correspondent over “several inexplicable differences with [his Melbourne editor], who seemed determined to show me that he, not I, ran the Washington office.” Returning to teach at Melbourne University, he was launched on his career as a public intellectual.

He campaigned to get rid of the White Australia policy, opposed the Vietnam war, and was a member of the Australian Committee for a New China Policy, urging recognition of the People’s Republic of China. Whether White Australia was an expression of protectionism, fear or racism, Grant argued that Australia’s obsession with the risks of being a Western outpost in Asia was starting to break down “into more manageable proportions.” He used White Australia and support for the policy of Forward Defence (embodied in Australia’s participation in the Vietnam war) as a litmus test of Australian attitudes in the 1960s:

If you were against White Australia and in favour of Forward Defence, you were liberal, anti-communist and internationalist. In favour of both White Australia and Forward Defence made you conservative, anti-communist and nationalist. In favour of White Australia and against Forward Defence made you nationalist and isolationist. If you were against White Australia and against Forward Defence you were liberal, internationalist and probably pacifist.

Asked to return to the Age as a regular commentator, Grant demanded conditions any journalist would treasure. He got written agreement that his column would be independent of the paper’s editorial line, that his copy could be altered only after consultation and that he would be given a research assistant.

While opposing the Vietnam war as a threat to Australia’s credibility in Asia, he embraced the US alliance, stronger Australian defence and, if needed, conscription for compulsory national service. He was “not confident that Australia could manage the challenge from Asia without the alliance with the US.” The formulation he later devised is that Australia could be “double-jointed” (not two-faced), embracing both the alliance and Asia. The image was of the two hands of a batting cricketer, flexible rather than rigid.

Grant saw the election of Gough Whitlam’s Labor government in 1972 as representing a new Australian confidence. His public support for Whitlam caused a breach with the Age’s editor, Graham Perkin, that entered Melbourne journalistic folklore. The disaster of the Vietnam war had encouraged “isolationism” on both the left and right of Australian politics, he writes, but in Whitlam he saw a fresh optimism for engaging Asia. He quotes Whitlam’s pronouncement that “an isolationist Australia would be rich, selfish, greedy, racialist and reactionary. Beyond doubt, we would be supporting this sort of society with the nuclear bomb.”

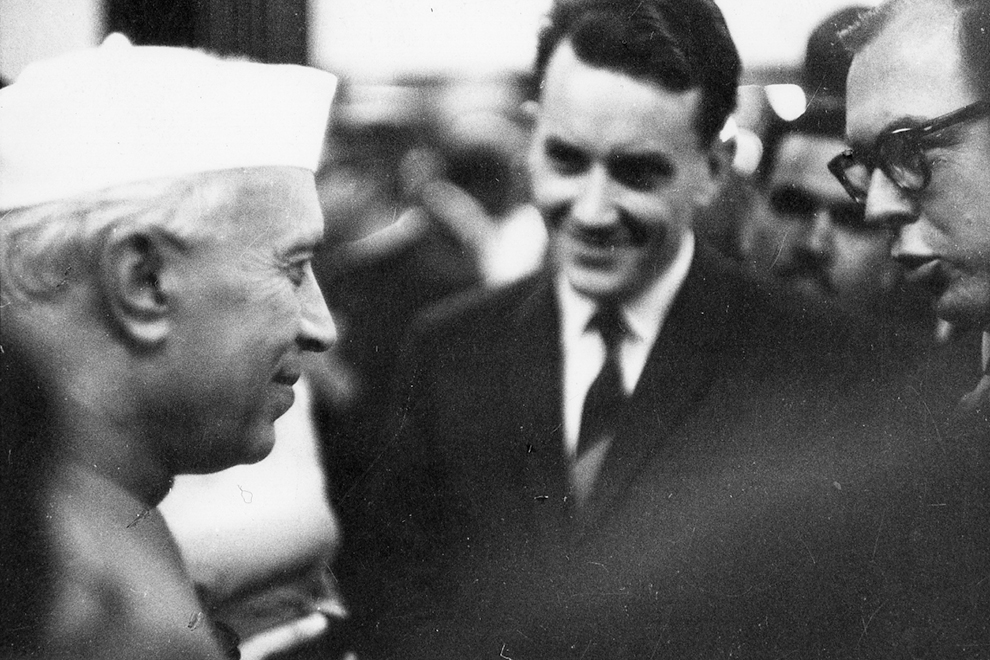

In office, Whitlam used Grant as an adviser and “startled officials at a meeting by introducing me as his Dr Kissinger.” The label became “Guru” when Whitlam appointed Grant as Australia’s high commissioner to India. “Neither of us paid attention to whether I had any of the formal skills or attributes of a diplomat,” Grant writes. “One of the delights of the Whitlam era – and a possible explanation of why it was so short-lived – was that those involved in it were confident they could do anything.”

Although Grant judges the Whitlam government “accident-prone,” he believes that it broke “the foreign policy mould of fear and deference.”

Australia’s progress gets most of the wordage in Subtle Moments, but Grant also describes three marriages and a love affair. This is a life that has gone through its share of scene shifts and character changes. His first wife, Enid, was an Australian, his second, Joan, an American and his third, Ratih, an Indonesian. In a book where the personal journey reflects that of the nation, these loves – Australian, American and Indonesian – carry geopolitical symbolism as well as adding up to a life’s emotional experience.

At the book’s close, as Grant contemplates his mortal end, he turns to an Australia that is merely beginning. Once race was “the heart of our being.” Now the creation of a multicultural society, he writes, “is probably the greatest and most surprising achievement of modern Australia.” This is optimism from a man who once worried that Australians might be a second-rate people because of stubbornly held low expectations.

Our geopolitical identity, long considered to be our nemesis, has become an asset,” he writes.

We are sited in a region that is increasingly powerful but not culturally defined. This also suits Australia. Once the odd man out, now the odd man in, we are uniquely placed to be an agent of peaceful change in our region.

Whether the region is called Asia or the Asia-Pacific or Indo-Pacific, it is a fusion of diverse values and customs: its essence is “networks, not institutions, and the energy of these networks comes from small and middle-size countries as well as big and powerful states.”

A pragmatic spirit will suit Australia: “We have shown, in a short span as a nation state, an unusual sympathy with the practicalities of ordinary life.” Asia can reach for informal consensus rather than discrete agreements. Grant cites Henry Kissinger’s vision for an Asia united by broad concepts of “community” and “shared enterprise.”

Australia faces a world that is unsettling and fractious, but not yet dangerous. By the fortune of both history and geography, the country is unique. And Australians have “no choice except to respond to the existential challenge of where they live.” As so often, responding to chance and challenge will bring out the best in Australians – a sceptical, practical people, as ready for drought as for bounty. •