“An Australian citizen does not approach this Court as a suppliant asking for intervention by way of grace,” said Isaac Isaacs, the fourth appointee to Australia’s national court, ninety-seven years before George Pell asked the High Court of Australia to hear his last-chance appeal. “He comes with a right to ask for justice, and I hold that our sole duty in such a case is to see whether justice to him requires an appeal to be allowed.” The future chief justice and governor-general (and distant relative of mine) was characteristically in dissent.

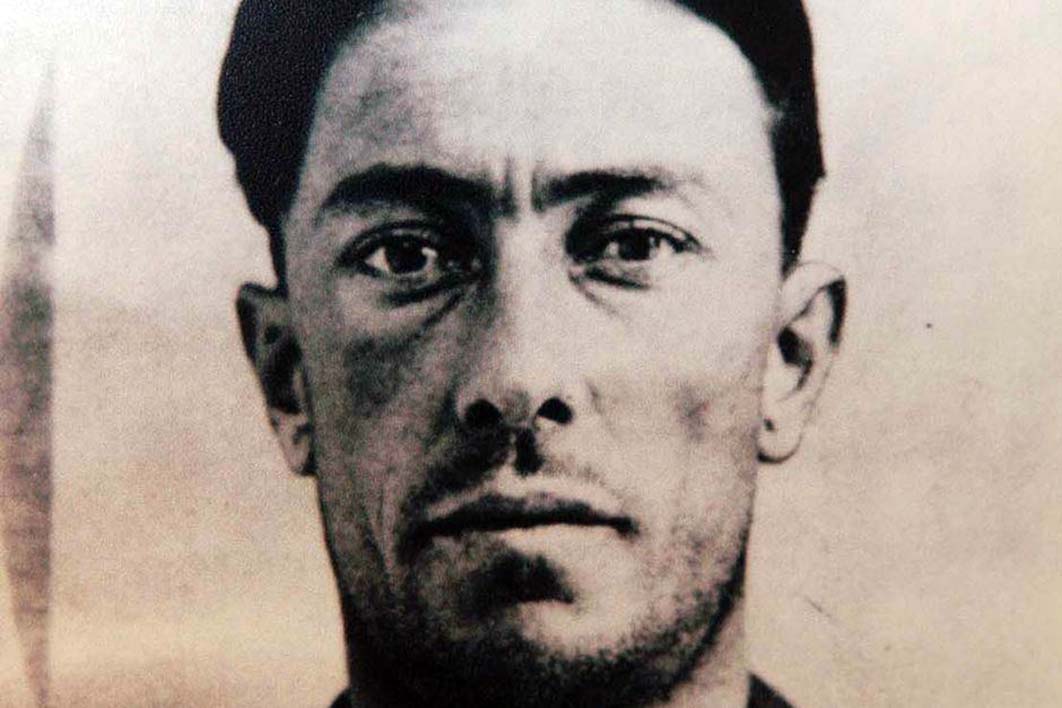

Isaacs wrote those words when the nation’s top court confronted what was, until recently, the highest-profile criminal case in Victoria’s history. From the moment the “outraged” body of twelve-year-old Alma Tirtschke, the dux of Hawthorn West Primary School, was found in a city alley on the final day of 1921, Melbourne and its media were transfixed. They remained so when police arrested wine bar owner Colin Ross for her murder two weeks later, and through his six-day trial and his appeal before Victoria’s Supreme Court. Now it was the High Court’s turn in the spotlight.

What role should a national court play in the nation’s criminal cases? That question has been debated for much of the High Court’s history. When the Australian Constitution’s “founding fathers” devised the nation’s new “federal Supreme Court,” they were inspired by its United States counterpart but decided to give the Australian court an extra role. On its creation in 1903, the High Court had the power to choose — “grant special leave” — to hear appeals from every court in the country, a role it initially shared with the Privy Council in London. At the time, most criminal convictions couldn’t be appealed, but that changed just four years later when England, reeling from a spate of miscarriages of justice, created a court of criminal appeal and the rest of the Empire followed suit.

These developments left the top courts in Britain and Australia in a quandary, each of them loathe to provide a second level of appeal to every convicted criminal in the Empire or nation. In 1914, the Privy Council decided to intervene only in criminal cases that would create an “evil precedent in future.” The High Court promptly made the same decision (over Isaacs’s furious dissent), but abandoned that stance as unworkable just six months later. The judges then declared that their “Court has an unfettered discretion to grant or refuse special leave in every case.”

Seven years later, Colin Ross understandably opted to bring his last-chance appeal to the High Court in Darlinghurst rather than the Privy Council in Westminster. His barrister flew to Sydney armed with a fistful of reasons for the national court to grant special leave, including fresh evidence, procedural errors at the trial, and unchallenged evidence of an alibi at the time of the murder. But he found a national court acutely aware of how “special” his case was.

“Our practice as to allowing appeals in criminal cases is more liberal to the prisoner than that adopted by the Privy Council,” allowed the majority, “but we must never lose sight of the fact that, in regulating our practice, the interests of the community, as well as those of the prisoner, have to be considered.” The majority judges’ particular concern was that allowing criminal defendants a second appeal “might amount to practical obstruction of the ordered administration of law.” They didn’t say what they meant, but everyone knew.

Three weeks later, Ross promised his family that “the day will come when my innocence will be proved.” Hours later, he became the first High Court litigant to hang, dying in agony following a botched execution. Forty-four years later, the national court similarly refused special leave to the last such litigant, Ronald Ryan, who told his hangman, “God bless you, please make it quick.”

It is always startling to see how justice used to be done. Colin Ross’s journey through the criminal justice system — arrest, committal, trial, appeal, denial of special leave, and execution — took just three months from go to woe. By contrast, it has now been nearly thirty months since George Pell was charged and eleven since his conviction for child sexual offences. Pell received neither death nor life in prison, but rather a six-year sentence. A loss in the High Court will still leave him free on parole in around three years (but also officially branded a sex offender for life and beyond).

On the other hand, Ross’s application for special leave received a three-day hearing before five judges of the High Court, who issued a twenty-two-page judgement the following Monday, including a concurrence and a lengthy dissent. By contrast, had Pell lost last Wednesday, his case would have ended with neither a hearing before the national court nor an explanation from the mere two judges who would have considered his case. Even now, his application for special leave could still be dismissed without any explanation, albeit after a hearing before at least five judges.

These changes in the national court are relatively recent. For its first nine decades, the High Court routinely gave convicted suppliants the treatment they gave Ross, with five or more judges hearing full arguments on whether they should grant special leave. Procedurally at least, there was no difference between the famous — Ronald Ryan (in 1966), Lindy Chamberlain (in 1983) and Roger Rogerson (in 1992) among them, all of whom received five-judge hearings of their applications for leave — and the less famous.

But such hearings are now a relic. A few years after Australia’s parliaments ended petitions to the Privy Council, the High Court started listing all applications for leave before small panels of judges: three at first and then just two. The hearings were speedy affairs, with a dozen or so scheduled for a single day, twenty minutes given to each lawyer to make their case and no reasons for the judges’ decision. More recently, the High Court announced it wouldn’t even do that much for most cases, instead simply publishing bimonthly lists of applications with the words “granted” or (almost always) “dismissed” next to them.

When news emerged last Monday that George Pell’s case was to be included in that week’s list, it looked like his case could end not with a bang but with a whimper. (Word of his listing somehow leaked from the court thirty-six hours ahead of its usual release.) Most cases dealt with in this way lose, but that’s because most of them are hopeless. The former archbishop’s sex-offending convictions were being dealt with in the same way as some guy trying to pay his taxes with a “promissory note,” or umpteen immigration appeals.

I was making no predictions this time. The High Court’s special leave decisions operate as a black box, with listings, selections of judges and the ultimate decision never explained. The odds are always against a grant of leave, especially when the case isn’t given a public hearing. On the other hand, special leave has been granted “on the papers” in seven cases so far this year.

So, no one should have been surprised by either a grant of leave or a refusal last Wednesday. Instead, the big surprise was that the national court did neither.

“In this application,” said Michelle Gordon, the High Court’s fifty-second justice, speaking also on behalf of its fifty-third, “Justice Edelman and I order that the application for special leave to appeal be referred to a Full Court of this Court for argument as on an appeal.” The waiting media could tell that Pell’s case wasn’t over yet, but were understandably baffled. What just happened?

The answer is that the High Court — or perhaps just its two most junior judges — had opted to deal with George Pell’s case the way it used to deal with most criminal appeals until the early 1990s. Pell would make his pitch for the national court to take his case before at least five justices, rather than the usual two, just as Ross, Ryan, Chamberlain, Rogerson and a thousand or so other convicted criminals once had.

Did Pell get singular treatment? No and yes. No, because this is at least the thirtieth time the High Court has dealt with a special leave application in this way in the past decade, including more than a dozen criminal appeals. Yes, because it is the first time it has done so in five years, since around the time the national court stopped holding hearings for most applications.

What will happen now? Most likely, Pell’s case will proceed like any case for which leave has been granted. The parties will put in full written arguments. (The court’s website already has a timetable up: we’ll read the arguments from Pell’s lawyer, Bret Walker, early in January and then the responses from Victoria’s top prosecutor, Kerri Judd, early in February, suggesting a hearing in March or maybe April.) The judges will likely “reserve” their decision after a day’s arguments and Pell will learn his fate around June.

At least, that’s how around three-quarters of referrals to five-judge panels turn out. The court sometimes does things this way to prod a proceeding along at one party’s request. (There’s been no word that Pell or his prosecutor asked.) And sometimes the judges want their suppliant to refine the grounds of appeal. (The court keeps any such letters to the parties secret from the public.)

Less often, the national court just wants to retain the option of staying with the case as long as it wants but ending its involvement at will. “The trapdoor can open at any moment,” Justice Dyson Heydon once told two tax evaders in Pell’s position nine years ago. It stayed shut in their case, but has opened in half a dozen others this decade. Pell’s case may end similarly next March, with the judges suddenly returning from lunch or a short break and ending the hearing without explanation.

Or perhaps the High Court had a reason specific to Pell. There’s a precedent of sorts in a recent high-profile case. In 2015, Queensland prosecutors’ application for leave to argue that Gerard Baden-Clay’s conviction for murdering his wife Allison should be restored was likewise dealt with “on the papers,” meaning that the controversial case had just one live hearing in Australia’s top court. The five judges sat in Brisbane and needed to provide an overflow room with a live feed to accommodate all of the spectators. The circuses that accompanied Pell’s Victorian hearings make it easy to see why the national court would avoid holding two hearings in his case.

The difference in Baden-Clay’s case, though, was that the High Court opted to grant special leave on the papers, rather than defer the prosecutor’s application to the next hearing. Why didn’t the court do the same with Pell? We will never know, but I wonder if the court’s hesitation this time was about whether its current processes could withstand the public scrutiny that is applied to all things Pell. How can such a controversial case be judged (and, especially, ended) by just two judges out of a bench of seven, with no reasons given? That question — which I think ought to be asked about every criminal appeal that reaches the national court — would have been front and centre of any coverage of Pell’s application, but for the High Court’s surprise decision on Wednesday.

The High Court has been involved in many divisive cases before, but they are usually constitutional cases on which all seven judges sit. It has also been involved in many high-profile criminal cases, but, since the national court stopped giving convicted suppliants hearings before at least five judges, none so divisive as Pell’s. It is the only comparable national court that currently resolves applications for leave to appeal in criminal cases with just two judges. The US Supreme Court takes cases whenever any four of its nine judges want to. New Zealand’s top court assigns panels of three of its five judges to hear every application and provides brief but specific reasons for every refusal. The Supreme Courts of the United Kingdom and Canada likewise assign panels of three to each application, and also provide an automatic right of appeal where, respectively, a lower court certifies a case of worthy of further consideration or at least one judge dissented from the lower court’s ruling.

It’s obviously a delicate matter to hint that any court has given different treatment to a particular high-profile case. The High Court and any lawyer who appears before it would be very vocal in denying such a possibility. But I see such a suggestion as less about the public sensitivities surrounding Pell and more about the institutional sensitivities of any national court that is forced to make sharply contested decisions where emotions run high. Indeed, much the same could be (and has been) said of recent decisions by Britain’s top court and coming ones in the United States.

We cannot (and should not) expect a court’s judges to wholly ignore how, in a high-profile case, they — and their processes — will also be judged. In the case of the four judges who denied special leave to Colin Ross, the final judgement came fifty years after the last of them died. In 2007, Victoria’s Supreme Court — relying on fresh evidence — recommended Ross’s posthumous pardoning for the murder of Alma Tirtschke. •