Making Chinese Australia: Urban Elites, Newspapers and the Formation of Chinese-Australian Identity, 1892–1912

By Mei-fen Kuo | Monash University Publishing | $39.95

Unlocking the History of the Australasian Kuo Min Tang 1911–2013

By Mei-fen Kuo and Judith Brett | Australian Scholarly Publishing | $34.95

IN FEBRUARY 1912 Chinese around Australia celebrated the founding of the new Chinese republic following the downfall of the Qing dynasty. In Perth, a chartered steamer flying the republican flag took a group of more than 300 on a river excursion to Applecross. In Townsville, a day of celebrations began with fireworks and flag-raising, followed by a picnic lunch and foot-races at Cluden. Adelaide’s Chinese drove out to the hills, where they lunched, competed in sports races and listened to tunes played by a Chinese string band. The streets of Melbourne’s Chinatown were festooned with flags and electric lights, and a large picnic was held on the bay in Aspendale. In Sydney, a picnic at Clontarf was enjoyed by more than 3000 of the city’s Chinese residents and their European friends; amid the eating and drinking, community leaders gave speeches rejoicing in the possibilities of the new China.

The mainstream Australian press reported on these Chinese festivities in sometimes intriguing detail. The Adelaide Register listed the results of the sports races held at that city’s celebratory picnic: the Chinese race was won by Lew Tung and Ah Kow, while the curious game of “Ladies Pinning On Pigtails” was won by Mrs Quarg Young and Mrs Penfold. The Launceston Examiner described the dress of the fashionable young picnickers from Melbourne: for the men, it was a straw boater, white silk shirt, blue serge sac coat, white trousers and white canvas shoes. And among the reports on Sydney’s “monster picnic” was almost a column of the Sydney Morning Herald dedicated to recording the speeches of the dignitaries, James Ah Chuey, William Yinson Lee and local parliamentarian, Dr Richard Arthur.

Chinese Australians were already great picnickers. They picnicked to celebrate Chinese New Year, Qing Ming, Guan Di’s birthday and other traditional holidays, as well as the birthdays of Confucius and, before the revolution, the Emperor of China. In Making Chinese Australia, Mei-fen Kuo notes how picnics were a sign of middle-class affluence and independence among urban Chinese in Australia, intended to present a positive image of the Chinese to the Australian mainstream. They were, in Kuo’s words, an “ethnic public-relations exercise” that Chinese community leaders hoped would advance their position in wider society.

Making Chinese Australia details how, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Chinese-Australian community leaders worked to shape perceptions of the Chinese in the eyes of mainstream Australia and to shape the attitudes and behaviours of Chinese themselves. Kuo argues that Chinese Australians were “made, not born” and sets out to document the process by which Chinese immigrants came to participate in Australian life, within a variety of local, national and transnational contexts. Kuo brings to this endeavour impressive bilingual research skills, polished as a PhD student and then a postdoctoral fellow at La Trobe University. She is currently a research fellow at Swinburne University of Technology.

Kuo’s main sources for Making Chinese Australia are the Chinese-language newspapers published in Sydney and Melbourne from the 1890s, sources that, in her words, “exemplify the thinking about self, ethnicity, class, gender, society and nation through which Chinese Australians made sense of their need to make Australia home and at the same time help to build the Republic of China.” Kuo uses the newspapers not just as a source of facts about people and events, but also as a way of understanding how Chinese-Australian community leaders – the men who established and edited the newspapers, as well as founding and running businesses and political and social organisations – worked with their communities to promote a modern Chinese identity.

The book centres on the activities of Chinese merchants and the urban elite – men like James Ah Chuey and William Yinson Lee, who spoke at the Sydney celebrations for the new republic in 1912. James Ah Chuey had arrived in Australia in the late 1870s, and from the late 1880s had built a successful business in the wool trade from his hometown in Junee. Ah Chuey was active in the Yee Hing Society (also known as the Chinese Freemasons) and was president of the Young China League, which became the Australian Kuo Min Tang, or KMT. William Yinson Lee was of a different generation, the Australian-born eldest son of W.G.R. Lee, who had been a bilingual community leader in Sydney before the turn of the century. William Yinson Lee became managing director of his father’s Sydney-based firm On Yik Lee & Co. and later a leader in both the Chinese Freemasons and the KMT.

These men were just two of the players in the history of Chinese community politics recounted in Making Chinese Australia. At the turn of the twentieth century there were more than 30,000 Chinese, both migrants and those of Australian birth, living in Australia. Kuo’s book deftly shows how this community was made up of different social and political groups, divided along lines of native-place, kinship and class but united by shared ideologies, religious beliefs, education and business pursuits. While the multitude of personal and organisational names and the frequent changes in organisational leadership and structure described in the book can be bewildering, it is this detail that brings out most clearly the diversity of backgrounds, attitudes and experience among the leaders of the Chinese community and within the Chinese Australian population.

Making Chinese Australia finishes with the founding of republican China, the moment that marks the beginning of Kuo’s other new book, Unlocking the History of the Australasian Kuo Min Tang 1911–2013, a slim, heavily illustrated volume co-authored by political historian Judith Brett. The Australian branch of the KMT started out in 1910 as the Young China League, which had been set up to support the revolutionary aims of Sun Yat-sen. After 1911 the league became part of Sun’s KMT party, with Sydney as the Australasian headquarters. The KMT drew members from across Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and the Pacific, and still has active branches in Sydney and Melbourne today.

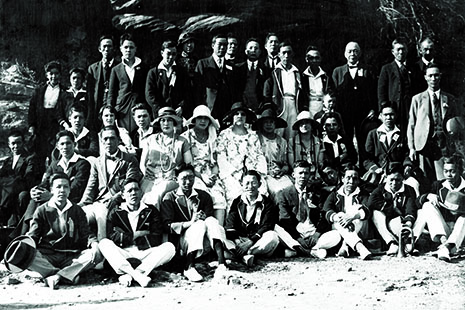

This book is one outcome of an Australian Research Council–funded project to open up and analyse the archives of the Australian KMT, a century of records that document the organisation’s political, social and community activities. We get some impression of the richness of these archives from the impressive collection of photographs reproduced here, but the collection also includes membership records, meeting notes, correspondence, publications and financial accounts. Kuo and Brett present a very readable account of the organisation’s history, placing it within the context of China’s shifting political landscape over the twentieth century and Australia’s changing response to both the Chinese nation and Chinese Australians.

Both books make a valuable contribution to understanding life under White Australia for the Chinese community. Chinese Australians had been excited by the possibilities Federation seemed to offer for uniting Chinese across the country and ensuring their rights alongside those of other Australians, and they were shocked by the introduction and reinforcement of laws and attitudes that showed this would not be the case. Chinese who were naturalised British subjects soon realised, for example, that they would not hold the same rights as white British subjects in the new Australia.

Importantly, Making Chinese Australia describes the impact of anti-Chinese sentiment and action on a community that had envisioned the contribution Chinese would make as individuals and as a community to the building of the new Australian nation. Among the manifestations of this growing realisation were the accounts of oppression that featured in the Chinese-language press in the early twentieth century, and the tales of suffering and hardship that became a part of Chinese-Australian identity. These narratives still have strong meaning within parts of the Chinese-Australian community today, as shown by calls in recent years for an official apology for historical discrimination against the Chinese.

FROM the outset, Kuo makes it clear that Making Chinese Australia focuses on a particular group within the Chinese-Australian population, the urban elite of Sydney and Melbourne, and it soon becomes evident that by this she means a male urban elite. The Chinese population in early twentieth-century Australia was certainly predominantly male (in 1901 only 6 per cent of Chinese residents were female) and with the book’s focus on politics and business perhaps a focus on men was to be expected.

Kuo notes though that women and children became increasingly involved in public community activities after the turn of the century and that attitudes towards women differentiated progressive organisations from their more traditional counterparts. But she only mentions a handful of women in the book and even fewer by name. One of these, Sarah Young Wai, a minister’s wife, worked among the Chinese in inner-city Sydney. Mother to a large family herself, her work was particularly important in providing support to other Chinese women in the city, including those who had bound feet.

Kuo does hint at a further, less obvious role that women and family played in her story of networks and alliances between men. She notes, for example, that James Ah Chuey’s extensive social network was cemented through marriage alliances and extended family relationships among the Siyi Chinese in southeastern Australia. One might ask, too, how the activities and attitudes of community leaders like Quong Tart, Sun Johnson and Charles Yee Wing were influenced by their marriages to Australian women of European ancestry.

The photographs in Unlocking the History of the Australasian Kuo Min Tang show women’s presence and participation in Chinese community life – at picnics, dinners, balls and as members of various committees. Despite this, though, women are again almost invisible in Kuo and Brett’s narrative of community leadership and the KMT’s engagement with the wider social and political environment. Historian Julia Martínez has noted that the Australian KMT was dominated by men, as Kuo and Brett’s history clearly shows, but there were exceptions, such as Lena Lee, who was vice-president of the Darwin KMT in the 1920s, and her sister-in-law Selina Hassan, who held the position of secretary in the 1930s. As Kuo and Brett state, the KMT distinguished itself from other Chinese organisations in its support for female suffrage and women’s political involvement, yet I was left wondering exactly how this translated into practical action for Chinese-Australian women.

Making Chinese Australia is a significant achievement in the field of Chinese -Australian history. Kuo is one of very few historians currently working in that field who has seen the results of their doctoral research published as a book. Many of the classic works on the history of the Chinese in Australia – for example, C.F. Yong’s The New Gold Mountain (Raphael Arts, 1966), Andrew Markus’s Fear and Hatred (Hale & Iremonger, 1979), Kathryn Cronin’s Colonial Casualties (Melbourne University Press, 1982) and Jan Ryan’s Ancestors (Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 1995) – resulted from just such a process, yet few of the excellent theses awarded over the past decade have yet made it to print. Michael Williams’s 2002 thesis on the transnational connections of the Sydney Chinese and Amanda Rasmussen’s detailed study of the Chinese in Bendigo from 2009 are among those that are worthy of a wider audience and complement the themes of Kuo’s work.

Making Chinese Australia retains more of the structure and tone of a thesis than is perhaps ideal (including an errant “in this thesis”) and would have benefited from a close final proofread to eliminate some minor editorial issues. That said, the book’s publication adds greatly to our knowledge of the organisation and leadership of the Chinese-Australian community, firmly placing it in both its Australian and transnational settings, and it should proudly take its place alongside John Fitzgerald’s Big White Lie (UNSW Press, 2007) as one of the new classic texts on Chinese-Australian history. •