Bedrooms of the Fallen

By Ashley Gilbertson | Chicago University Press | $49.95

The French newspaper la Nouvelle République recently ran a story about a bedroom. This remarkable room – spacious, airy, with a view of trees – belongs to a large, comfortable and otherwise unremarkable house, located in the village of Bélâbre in central France. The room has been preserved, to all intents unaltered, for ninety-six years, ever since its last occupant, a young soldier called Hubert Rochereau, died in Belgium, on 26 April 1918, from wounds received in battle. His devastated parents reacted to their loss by preserving the room very much as it was on that day. Perhaps, we can surmise, they added mementoes and reminders as time went on, as these items were returned to them or discovered later in cupboards and drawers in other rooms of the house. We can also surmise that they arranged and rearranged objects on his desk and on the walls, deploying the physical evidence of their son’s brief past – he was twenty-one when he was killed – to best represent him for the future. Testifying to the fact that Hubert Rochereau had only recently left childhood behind when he went to war, his schoolbooks are lined up on shelves besides his bed.

With the centenary this year of the beginning of the first world war, the subject of memory and memorialisation – what should we remember and what should we forget? – has been very much in the air. The story of Hubert Rochereau’s bedroom has played directly into that debate. It has been picked up by news outlets around the world and continues to appear in a variety of publications and on social media. In one of a number of clips viewable on the web, we can see a television reporter from the BBC entering the room and being struck by the way it evokes a life. She smells the cigarette tin that contains cigarettes once rolled by Rochereau, and marvels that the odour of tobacco is still present. In a video clip from the London Telegraph, the present owner of the house, Daniel Fabre, speaks of this unusual legacy. When Rochereau’s parents reluctantly gave up the house, in 1935, they tried to impose a condition on all future occupants, that Hubert’s room would be preserved exactly as it was, for 500 years. As Daniel Fabre points out, the condition has no legal standing. But he abides by it all the same, just as his predecessors have done. “Whatever happens after me, I couldn’t care less,” he says at one point, but it is clear from the expression on his face that he does indeed care.

Wherever it appears on the web, this story tends to attract a lot of comments. Apart from the usual instances of comment-humour – is that a flat-screen television I can see in the corner? – most by far of the contributions from readers are reverent, reflective, a touch sentimental. The creation of this memorial to a son’s death may be untypical and extreme, but at the same time it is ordinary and perfectly understandable. What is 500 years, after all, in the face of so terrible an event? (This private and, until recently, little-known memorial echoes a more famous one to be found not far away, in the village of Oradour-sur-Glane, where 642 citizens were murdered by the Waffen-SS in 1944; the village has been left exactly as it was, a memorial to the dead, the only changes being the slow and often imperceptible ones wrought by the elements.)

In several of the many photographs and videos of Hubert Rochereau’s room that can be found online, we can see, hanging above his undersized bed, an oversized, full-length photographic portrait of Hubert in the uniform of the Dragoons. He has that quasi-confident pose typical of such photographs, his moustache making him look, as was the point, older than his years. Such photographs were intended for the families and loved ones left behind, to function as reminders and mementoes during long absences and, should the worst happen, as memorials. The photograph, presumably placed in that resonant spot by his parents after his death, serves as a memorial within a memorial, linking the adult’s fate to the unfulfilled promise of childhood. The cigarettes and the items of military uniform draped around the room coexist with those schoolbooks neatly arranged in the bookcase, and the child and the adult merge. The purpose of such memorial spaces – arising from a need to keep things looking just as they were – is not so much to freeze time; not even in the extremities of grief is it easy to believe that time can be stopped. It is rather to force and reinforce the act of contemplation and to ensure that the past and those who lived in it remain meaningful and immediate in the present.

The photograph and the untouched room function in similar ways – they preserve the past and invite us to contemplate it. Indeed a photograph is a kind of analogue of an untouched room – the two seem to go naturally together. The Melbourne-born photographer Ashley Gilbertson, best known for his images of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, has taken this conjunction as the subject of his most recent work, which has appeared in a number of exhibitions in the United States and Europe, as well as at the Australian Centre for Photography in Sydney, and has now been collected in book form as Bedrooms of the Fallen. After a career spent in documenting action, Gilbertson has chosen to focus on inaction, on the stillness of the space that the dead soldier has left behind, never to return.

In this transition from action to stillness, Gilbertson is tracing in particularly clear lines a path that is followed in one way or another by many who pursue photography as both a profession and a calling – it is a path designed to regain for photography the quality of stillness by creating an image or images that give the viewer pause and demand something more than a glance. It is not so long ago that action photographs – the kind that Gilbertson himself took many of in Iraq and Afghanistan and other conflict zones – could achieve that arresting quality, but that time is passing rapidly. The action shot now typically creates not contemplation and imaginative entry into the scene, but rather an expectation of the next frame, as if it is just one frame in a film or a video sequence.

Gilbertson has articulated this dilemma directly, even to the extent of calling into question the validity of his own earlier work. In a brief but revealing interview he gave in 2011 to the New York Times, the paper for which he has worked consistently for over a decade, he responds candidly to the question of where his idea for a series on “bedrooms of the fallen” came from. “The whole project” – of photographing the preserved bedrooms of young soldiers and other military personnel who have been killed in action or otherwise died as a result of war – “was in response to my failed work in Iraq.” Gilbertson’s “failed” work in Iraq had by this stage received numerous awards, including Time’s Picture of the Year in 2004 and the Robert Capa Gold Medal, the latter placing him securely in the pantheon of photojournalism. Yet, as he says in the same interview, “I have a book called Whiskey Tango Foxtrot from the war, and I have trouble connecting with the images myself… and I shot them.”

When Gilbertson laments the fact that “as time went on, people became less and less engaged with pictures of war,” he is referring not only to his own pictures but also to the genre of war photography itself, and to the difficulty in an image-overloaded world of saying anything new, or of having any meaningful influence on outcomes. A few years earlier, in 2007, in an essay written with Joanna Gilbertson to accompany a sequence of his Iraq images that appeared in the Virginia Quarterly Review, he was already expressing disillusionment with his own work, while continuing to look for some greater impact in the future, expressing the hope that “people who don’t recognise it now may one day look back at my pictures and see the war for the mistake-riddled quagmire that it was.” But in Bedrooms of the Fallen he is placing his faith in another kind of picture, one that forgoes action for consequences.

Given that Gilbertson began with action as his subject, and it made his career, this is a significant departure. During his teenage years in Melbourne in the nineties, he photographed what he knew – the world of skateboarding, of young life on the street – developing all the while a strong if unworked-out sense of vocation and a determination to travel to the trouble spots of the world to document oppression and injustice. There was a stint in Kosovo, and then another, clandestine one in Irian Jaya. And then, by a process that he has described as accidental, he found himself turning into a war photographer, a transformation that occurred at the very moment when the nature of war and the nature of photography were both undergoing profound and irreversible changes.

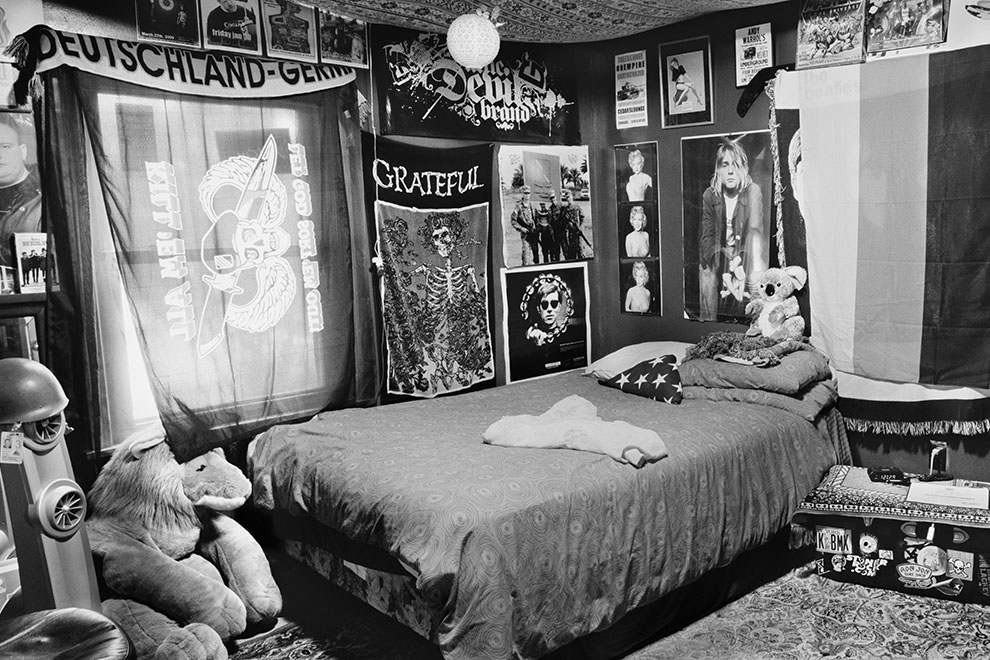

The bedroom of Army Private First Class Karina S. Lau, 20, who died when her helicopter was shot down by insurgents on 2 November 2003, in Falluja, Iraq. She was from Livingston, California. Her bedroom was photographed by Ashley Gilbertson in December 2009.

By 2002, at the age of twenty-four, Gilbertson was in Northern Iraq, focusing more and more on photographing scenes of combat. His work from that period quickly drew wider attention and by 2003 he was employed by the New York Times, from where he rapidly established a reputation as one of the best contemporary combat photographers. He returned repeatedly to war zones, principally Iraq, risking injury and death on many occasions. And yet, by the account contained in his afterword to Bedrooms of the Fallen, Gilbertson was already questioning the validity of a twenty-first-century career as a war photographer. He saw himself as following a model from the past, one that no longer applied. “As I worked through Iraq over the years, I thought of images by photographers like Matthew Brady, David Douglas Duncan, Capa, and James Nachtwey, and the impact they had made.” But times had changed – it was now the age of the “embed,” of the photographer not as free agent and impartial witness but as just another actor in the drama, controlled and manipulated by “the system” much like everyone else. “I was the next generation of photographer trying to act like one from a previous era.”

Many of the great photographers of war and conflict, of both the present and previous generations, have worried out loud that in the end their photographs have no real impact – that the wars go on regardless. What is newer is the link Gilbertson draws between the failure of impact and the changing nature of photography itself. The world is awash with photographic moments, many of them depicting much the same thing, slightly different versions of photographs that have already been taken. Gilbertson has lamented that during his time in Iraq he was increasingly feeling as though “I was doing … the same picture over and over again.” Not only, by his own account, were his photographs too much like other people’s, too much in the shadow of past masters, but they were too much like one another. It might equally be said that Gilbertson is doing the same picture over and over again in Bedrooms of the Fallen; the difference here is that the sameness is part of the point. The sameness does not diminish the impact but heightens it. The similarities of the rooms, and of the way they are photographed, encourages us to look more closely and to uncover in the details of the compositions the differences in the lives the soldiers have left behind.

“Today, photographers often prefer to wait until an event is over,” says David Campany in his study of the shifting relationships between still and moving pictures, Photography and Cinema (2008). Far from capturing the fast-moving moment as it happens, “they are as likely to attend to the aftermath.” In Bedrooms of the Fallen, Ashley Gilbertson is attending to the aftermath. It is one of the characteristics of “aftermath photography” that, from the photographer’s perspective, most of the effort is expended before the photograph is actually made. It can take years to set up a shot. Bryan Adams’s candid images of British servicemen and women who have suffered terrible injuries, for instance – published in Wounded: The Legacy of War (2013) and currently on display at Somerset House in London – were in preparation for five years. Many of the subjects “were hesitant,” recalls Adams, “and understandably so… For many of these people it was the first time they had ever been photographed, never mind exposing their wounds.”

For Gilbertson, it was the parents of the dead soldiers who needed to be certain of the wisdom of the project, and in order to provide that certainty he needed to be patient. By contrast, the actual business of capturing the images amounted by Gilbertson’s own reckoning to only “5 per cent of the process.” Indeed it sometimes seems as though he is dismissing altogether the operational aspects of taking the photograph – he can be vague, for instance, about the equipment that he uses or prefers to use, as though that does not really matter all that much. For Bedrooms of the Fallen, he says only that he “decided to use a panoramic camera and an extreme wide-angle lens.” And, he adds, he also decided to present the images in black-and-white, in order to emphasise his own neutrality, though this neutrality did not preclude a capacity and a willingness to intervene and to set the rules.

From the time when the idea for a series was first mooted, in 2008, Gilbertson determined that he would photograph only the bedrooms of people who were still “at home” at the time of their deaths, rather than those who had gone on to have homes and families of their own, and only bedrooms that had not been substantially altered, or given over to siblings, or remade for other uses within the home. Importantly, they would only be bedrooms where the custodians – the parents – understood and supported what it was Gilbertson was trying to do, and were willing to make the necessary leap of understanding and to give permission for their child’s life to be documented in this way. The result, in Bedrooms of the Fallen, is forty double-spread photographs, most of them of the rooms of American servicemen – and two women – with a leavening of others from coalition partners: the United Kingdom, Italy, France, the Netherlands. One from Germany, but none from Australia; even though Gilbertson is on record as hoping to have included an Australian component to the series, it has not eventuated here. (Though we do glimpse a possible Australian connection in the room of Dutch Soldier First Class Timo Smeehuijzen, where a boomerang perches high up on a wall.)

The panoramic lens makes the rooms seem both spacious and squashed up. Where windows are included in the shot we cannot see very much out of them. When it is not completely blocked out by drawn curtains or blinds, the outside world usually appears as white light, with perhaps the faint impression of a tree branch just discernible. The rooms have a safe but claustrophobic air. In most of the photographs we cannot see the doorway. Where we can, the door is closed or opens onto darkness. An exception, the image of the bedroom of Airman First Class Carl L. Anderson, appears first in the series. Here the doorway is open, and we can see the hall and another door beyond. The hall is brightly lit, and within the bedroom the two portrait photographs we can see of Anderson, one on the wall and the other on his dresser, show him smiling broadly.

We get a strong impression here of the energy and adventurousness that led him out the door, but in most of the companion images any such impression is outweighed by the evidence of lives suddenly stopped, right on the border of youth and adulthood. The photographs, most of them taken between 2007 and 2012 (sometimes after years of back and forth with the families) already have an historically dated air – as dated in their way as the images of the bedroom of Hubert Rochereau. The technology, predictably, is what most clearly gives the game away. The televisions, computer monitors, boom boxes, speakers, all of them contemporary or nearly contemporary with the time when the rooms were last occupied, now seem squat and unfashionably clunky. CD and DVD towers (Stargate SG-1, The Shield) likewise speak of a world already in the past.

In many of the rooms there is at least one soft toy, alluding to the childhood of the room’s occupant, and placed carefully on the bed or visible on a bookcase or a desk. The soft toys most clearly contribute to the generally arranged impression that the rooms give, an impression that seems to complicate any idea that these bedrooms have literally been left “just as they were.” Not only the parents but also the soldiers themselves are likely to have contributed to this effect. Gilbertson speaks of the practice of “editing,” whereby those about to leave home on active service will, in preparing for any eventuality, edit or curate their rooms to ensure that families will not come across anything embarrassing or distracting; to ensure, in other words, that they leave behind the best impression. Each of these rooms, once lived in, is now on display – the items we can see, from uniform jackets to trainers to talcum powder, are functioning as exhibits, representing a life. We are invited as viewers to conjure up that life, its reality and its potential. The arranged stillness of these rooms does not, paradoxically, make them lifeless – instead it helps to put the life back into them. •