April 2015 was a good month for me. In the space of a week I signed not only a marriage contract, but also something I’d been pursuing for much longer: a book deal.

I’ve been writing stories for as long as I can remember, but it was only in 2014 — after two decades of practice — that I finally finished my first novel, Greythorne, a Gothic mystery set in Victorian England. The writing process itself had been relatively short, just twelve months from the idea to a manuscript I was comfortable submitting to publishers. In November 2014 I took it to an Australian Society of Authors Literary Speed Dating event in Sydney, where I pitched to various agents and editors, and five months later one of those contacts bore fruit.

My contract was with a digital-first imprint of one of the Big Five (the five biggest book publishers in the United States: Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Hachette, Pan Macmillan and Simon & Schuster). Digital-first meant it would be available only in ebook and print-on-demand formats, so there’d be no big print runs or distribution to bookshops unless it happened to do very well. At the time I didn’t care; it was a foot in the door.

What followed was a stripping away of any illusions I might have had about the traditional publishing industry. I thought publishers were in the business of marketing books — because they presumably want them to sell. Once upon a time they were, but those days are long gone. These days, a new release has to fend for itself, and if it doesn’t strike paydirt within the first month, then it’s done its dash. But getting lucky is far more likely to happen in some genres than in others — romance and crime, for instance, have hugely dedicated readerships. It certainly doesn’t happen in Gothic mystery.

Of course, I was lucky to have been offered a contract at all. The market for my kind of book is relatively small, and Greythorne is short as novels go, at only 55,000 words, or a bit over 200 standard paperback pages (most publishers prefer them to be around the 80,000-word mark). The development of digital-first imprints — which several major publishers have started in an attempt to tap into the ebook market — means that publishers will sometimes take chances on books like mine, whereas they wouldn’t necessarily consider them for a traditional print run. But these imprints are also often tiny, run by a dedicated but small team of people within a very big company, without the resources to properly market their wares. Essentially, they’re often set up to fail, and this failure then reinforces everything the publishers think they know about the ebook market, namely that it’s impossible to make a go of. (It’s not — trade publishers just don’t do it very well — but more on that later.)

In mid 2016, the imprint I’d been contracted by closed down unexpectedly, or at least it was unexpected for those of us on the outside. A number of authors, me included, were left stranded. On the one hand, our contracts were with the parent company, so they were still valid as long as our books continued to be made available for sale. They were, but what little marketing support there’d been had disappeared. On the other hand, the publisher offered to give us back our rights, but then we’d have to decide what to do with them. I queried an agent about the possibility of pitching the book to another publisher and was basically told not to bother — it’s extremely difficult to resell an already published novel unless it’s a bestseller. I decided to leave Greythorne where it was for the time being, because at least people could still buy it. Then I started looking at options.

In the meantime, I’d begun working on another novel, The Iron Line. This was another Gothic mystery, this time set in Australia in the 1880s. The imprint’s collapse had taken away any temptation to take the path of least resistance by pitching it to them, but it also meant I was essentially back to square one in terms of finding a publisher and/or an agent. It was a demoralising thought.

Around the same time, an author friend introduced me to a Facebook group for “indie” authors. Indie, or independent, authors are what used to be known as self-publishers — people who produce and publish books themselves, in this case using ebook and print-on-demand technology. Indie publishing is very different from vanity publishing, where unscrupulous companies charge inexperienced authors to publish through them, often to the tune of tens of thousands of dollars, for little or no meaningful return. Indie authors subcontract services like editing and design themselves, and retain full control of all their intellectual property.

The indie scene underwent a renaissance in the late 2000s, spurred on by Amazon’s release of Kindle Direct Publishing, which allows authors to publish directly to Amazon’s Kindle ebook platform rather than having to go through a third party. In the ten years or so since then, indie publishing has developed into a thriving industry, with an array of services blossoming out of nowhere to support it. Self-publishers are no longer stereotypical narcissists with thousands of badly printed books in their basement; these days they’re businesspeople, and often quite successful ones at that.

Discovering just how many options are available to the modern author — far beyond the “contract or bust” model of yesteryear — was a revelation. But at the same time I baulked at the thought of going indie; deep down, it still felt like the easy way out, or second best to endorsement by a traditional publisher. So I left Greythorne languishing there in limbo, but nevertheless decided to find out exactly what this indie publishing thing was all about.

Entering the indie publishing world is a little bit like entering a parallel universe. Up in the firmament are a whole host of superstars you’ve probably never heard of — Hugh Howey, Joanna Penn, David Gaughran, K.M. Weiland, Kristine Kathryn Rusch, James Scott Bell — many of whom are making five-, six- or occasionally seven-figure incomes from their writing. Further down are the mid-list — people who aren’t quite indie superstars but who are making perfectly respectable money through savvy marketing. Of course, there are still traces of the old self-publishing problem evident in those books that lack decent design and/or editing, but that’s what happens in a democratic marketplace. You could sit the best-quality indie books next to traditionally published books and most people wouldn’t be able to tell the difference.

One characteristic of the most successful indie authors that I noticed early on is that they’re not just authors — they’re businesspeople. Many of them run mini-empires, built around not just their fiction work but also non-fiction, speaking gigs, workshops and other services. To succeed, indie books need to harness a whole marketing ecosystem — an email list, free giveaways, a spot in the coveted BookBub newsletter (which sends free or discounted deals to its subscribers every day and can add thousands to a book’s sales), and so on — and the most successful authors have learned how to make this work for them.

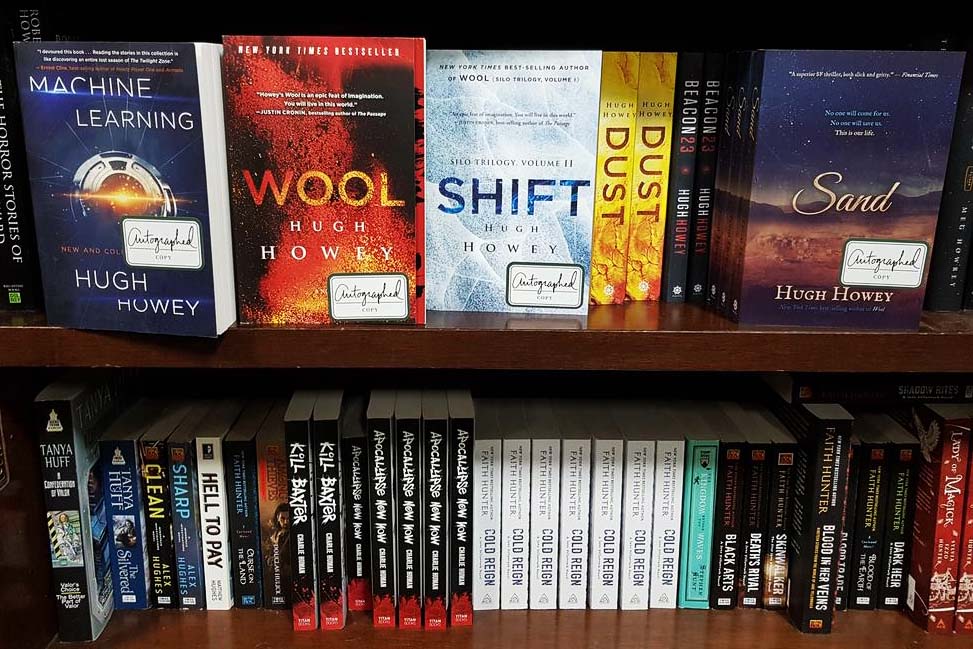

Hybrid strategy: Hugh Howey capitalised on his self-publishing success by striking print deals with major publishers but retaining lucrative ebook rights.

Strangely enough, though, techniques that would be a closely guarded secret in other industries are willingly shared in the indie world. Whether it’s through free sources such as Facebook groups and podcasts, or through non-fiction books, webinars and other media, indie authors are almost always ready to help each other out. In the indie Facebook group I’m part of, members regularly (and constructively) critique each other’s covers and blurbs, offer feedback on drafts, and answer questions about platforms and marketing strategies, even sharing the results of particular promotions they’ve launched and offering lessons learned. You might think that an industry in which members are competing to get their own work noticed would be incredibly vicious, but in fact indies across the board are really nice.

Even those who’ve had enormous success seem to see value in giving back to the community. Hugh Howey became famous as the first indie author to sign a print-only deal (retaining ebook rights because he’d done so well with them on his own) after his dystopian science-fiction trilogy, Silo, was picked up by Simon & Schuster for a six-figure sum. But he’s also known in the indie community as the brains behind the Author Earnings website, which is one of the few sources of sales statistics that don’t come from the major publishers (which don’t usually include ebooks or indie books). It aims to crunch the data across the entire marketplace and give a more accurate snapshot of exactly which types of books are selling and who’s producing them.

The traditional publishers hate this kind of thing because sales figures have always been a tightly held secret, but Author Earnings is in keeping with the openness of the indie community, which is all about sharing information to help authors make informed decisions. Likewise, one of the longest-running podcasts on indie publishing, The Creative Penn, run by British author Joanna Penn, regularly hosts guests from all over the world who share information on all aspects of indie publishing, from writing techniques to exploiting audio rights to getting the most out of Amazon ads. The amount of information available, often for free, is simply extraordinary.

All the same, indie publishing is a huge learning curve, and it’s not for everyone. Some writers just want to write, and that’s fine. As an indie author you have to do it all, and that means being comfortable with marketing. Once upon a time, highly introverted authors were able to hide behind their publisher’s marketing department, but not any more. Even in trade publishing, authors have to do the lion’s share of the work when it comes to getting their book out there, and in indie publishing this is magnified. If that’s not your thing, or if you’re not technologically savvy, you’re going to struggle as an indie author.

The other thing to bear in mind is that some types of books sell better than others. Romance readers, for example, are voracious and loyal, so romance is the perfect genre for indies because the market is huge. Likewise, crime tends to do well, especially “cosy crime” (think Agatha Christie) and thrillers. Speculative fiction — science fiction, fantasy, horror and all their various sub-genres — also has a pretty strong market, especially because the ebook retailers’ categories go into quite some detail, so readers can browse very specific varieties of the genre according to their taste. Steampunk, for example — a speculative fiction subset that has fantasy or sci-fi elements set in an alternative Victorian-era world — is a growing market, but not big enough for many traditional publishers to touch it.

On the other hand, middle-grade fiction (chapter books for children aged eight to twelve) is generally accepted as difficult to publish independently. Kids’ books in general are hard to sell this way because you have to market to the parents as well as the child, and these works tend not to be so popular in ebook form anyway. Likewise, if you write literary fiction then indie publishing is a bad idea, because it won’t sell — but then, literary fiction tends not to sell very well in any format, which is why traditional publishers use the earnings from genre fiction bestsellers to cross-subsidise it. Literary fiction authors also depend disproportionately on literary reviews and prizes, neither of which are particularly accepting of indie-published books. But for genre fiction authors like me, there are far more opportunities than ever before.

In early 2017, I decided to dip my toe in the indie publishing waters with a non-fiction book, Communications for Volunteers: Low-cost Strategies for Community Groups, which I’d written as an asset for my consultancy business (because, like most writers, I also have a day job). In this case, there was never any question of finding a traditional publisher; I deliberately decided to go indie because I wanted to retain full control over the intellectual property rights. I knew I’d be using material from the book in other aspects of my business, such as training courses, and I didn’t want to have to go running to a publisher for permission every time I wanted to do that. So indie it was.

As an entree to the industry I probably couldn’t have picked a more difficult book. It was full-colour with lots of lists and diagrams, so was a lot more complicated and expensive to format and print than a traditional black-and-white novel. Marketing non-fiction is also quite different from marketing fiction, and there are fewer resources available. But I got there in the end, and it made me realise just how much freedom and control you have over the entire process, from what you write, to design, release dates, sales and giveaways

By this point I’d finished the first draft of The Iron Line and was getting started on rewriting. It had taken longer than Greythorne (it turns out that starting a new business and finishing a novel aren’t always compatible) but it was rapidly reaching the point where I needed to decide what to do with it. I’d been toying with the idea of indie publishing from early on in the process, but had come up against the stigma that still exists around self-publishing. A successful author friend epitomised this when she said, on hearing that I was thinking of going indie, “Oh no, don’t do that — your writing is far too good and it’d be a waste of your talent.”

So I continued to weigh up my options — agent, major publisher, small press — and in July this year I again went to a Literary Speed Dating event. I had some muted interest, but also “we can’t sell Gothic” and some concerns about the length of The Iron Line, which, although slightly longer than Greythorne, is still on the short side. Even the fact that I already had one book published (and so was slightly less of a risk than a debut author) seemed to make little difference.

In the meantime, I watched Greythorne’s sales ranking slide without being able to do anything about it. If you can’t control the price then you can’t run sales, give books away for free, or implement any of the marketing mechanisms that will actually help it to sell. I knew that the dismal sales figures weren’t because it was a bad book — it had got good reviews, and I’d actually made some pretty decent money, albeit by buying print-on-demand copies and on-selling them myself, which is ultimately an unsustainable way of doing things. Finally, I decided that I wasn’t getting anything from the publisher that I couldn’t get myself, so I got my rights back and have recently re-released Greythorne under my own imprint. Suddenly a whole world of possibility has opened up, and I’m cursing having waited so long to do it.

I started thinking about The Iron Line systematically. What could a traditional publisher give me that I couldn’t get for myself? These days, publishers tend to outsource design and editing to freelancers, so these can be obtained at the same quality you’d get if you went through the trade press. Indies obviously have to finance these themselves, but then the potential returns are also far higher.

The one thing traditional publishers can provide is print distribution into bookshops. But the reality is that most books only stay on the shelves for a month or two, unless they happen to take off. Certainly books in niche genres, like mine, won’t hang around for long. And in any case, bookshops (much as I love them as a reader) only give access to the Australian market, which in global terms is minuscule, whereas indies have access to the entire English-speaking world — and beyond just the usual Western suspects. Some of the places I’ve gained the most traction have, oddly enough, been India, Malaysia and South Africa, and one of my longer-term projects for Greythorne is a Hindi translation.

Another important consideration, and the main reason why the indie mid-list is thriving while it’s all but disappeared from the traditional industry, is royalty distribution. On Amazon, which is still far and away the biggest ebook retailer, any books priced between US$2.99 and US$9.99 yield a 70 per cent royalty (for books outside those parameters it’s 35 per cent). This means that for every US$4.99 copy of Greythorne sold, I make US$3.50. I can’t divulge the royalty rate from my original contract, but I can tell you it was a lot less than that. If you choose to publish exclusively with Amazon, you can also enrol in their subscription program, Kindle Unlimited, which gives readers access to an unlimited number of books in exchange for a monthly subscription, with authors paid by the number of pages read as well as for normal sales.

Other retailers, such as Kobo, give authors a 70 per cent royalty regardless of price. Plenty of research has shown the sweet spot for ebooks — the point where the author will move the most copies but still get a decent return — to be around the three-to-five-dollar mark, which is why indie authors who are savvy with their pricing and marketing are often able to make a decent living. In contrast, most trade publishers still use ebook pricing primarily to drive sales to paperbacks (which is where they make their money), ignoring the many reasons why readers might choose to read ebooks instead. This is why you often see ebooks from traditional publishers priced at anywhere between $10 and $25, which means, of course, that they don’t sell anywhere near as well as their more reasonably priced cousins.

Even though most indie authors still make the majority of their income from ebooks, developments in print-on-demand technology have made indie paperbacks a huge industry. Gone are the days when a minimum print run was 1000 books, which you then had to store until you could sell them. These days, you just upload a file and it gets printed as people order copies. Amazon has its own print production company, CreateSpace, while one of the world’s largest producers of traditionally published books, Ingram Content Group, also runs a print-on-demand arm, IngramSpark, designed for indie publishers. IngramSpark also markets indie books directly to retailers and libraries in the same way that Ingram sells its traditionally published books, meaning that it’s easier than ever for indies to get their work out there.

The other exciting area where indies are leading the way is audio. In the last five years, the audiobook market has taken off, driven in large part by the ubiquity of the smartphone and the resultant podcast revolution, which changed people’s listening habits. Most traditional publishers, realising just how valuable audio rights are, will now force authors to sign them over (whereas previously you could choose to retain these and nobody cared), even if they have no intention of exploiting them, which deprives authors of a valuable asset. In addition, unlike with print books, it’s not possible for authors to pitch directly to audiobook publishers such as Bolinda. They deal directly with print publishers, so even if you retain your audio rights, there’s no way you can get an independent deal with them.

Unsurprisingly, Amazon is leading the way in indie audiobook production, like it did with ebooks, through its own platform, Audiobook Creation Exchange. ACX pairs authors with narrators, through either a fee-for-service or royalty-sharing arrangement, and then publishes the audiobook to Amazon’s massive Audible platform, as well as to iTunes. Books published on Audible are also made available for sale on Amazon alongside the ebook and paperback versions, and it’s becoming increasingly common for customers to buy both the ebook and the audiobook, especially as they sync on a smartphone or tablet to allow seamless transitions between the two formats. (You can read up to a certain point in the ebook, and the audiobook will pick up where you left off, and vice versa.)

But ACX isn’t available everywhere — Australia, as you might expect, is one of the places yet to receive it — and other companies such as Findaway Voices are rapidly filling the gaps. The growth of in-home voice-activated services such as Google Home and Amazon Echo is also likely to bolster the audiobook market, and indies are in a prime position to take advantage of it.

Looking at it this way, in cold, unemotional business terms, it was clear to me what the best option was. But if this sounds like an easy decision, it wasn’t. Indie publishing is hard work. It also, strangely, felt a bit like admitting defeat. I hadn’t realised how deeply I’d internalised the idea that the only people who self-publish are those who can’t get a traditional contract.

Thankfully, this perception is gradually changing, especially as more and more well-known authors start choosing the hybrid model — some books published traditionally, some indie. In December 2016, bestselling Australian author John Birmingham (He Died with a Felafel in His Hand) announced that, although he still had some trade contracts, he was going to be indie publishing a lot of his work from now on, after a falling-out with his publisher. Such high-profile defections help give legitimacy to indie publishing, as does the fact that many publishing awards are now increasingly open to indies. In fact, the annual ACT Publishing Awards are open only to books published either independently or by small presses, in recognition of the fact that high-quality work exists outside the publishing mainstream.

For me, ultimately, it came down to freedom. I certainly don’t expect to make my fortune overnight — indie publishing is a long game — but I have control over my own destiny, and that’s hugely important to me. Indie publishing gives me freedom not just in the business sense of deciding release dates, pricing and when to run sales, but also creatively. The accepted wisdom in traditional publishing is that once you publish your first novel you need to keep writing more of the same in order not to confuse readers, but in indie publishing, you can write whatever you want. It’s true that deviating hugely from your normal genre may not be the best business decision, at least under the same name, but if I want to jump from Gothic mystery to steampunk, for instance, that’s not such a huge leap. Realising I have the freedom to experiment creatively and to take risks (some of which may not pay off, but some of which I’m hoping will) is incredibly liberating. And even if I lose the respect of many in the traditional publishing industry, I can connect directly with my readers, which is one of the things I love most about being an author.

For many writers, a traditional publishing contract will still be the pinnacle of success, and others just want to write without the pressure of running their career like a business. And I haven’t ruled it out entirely; if the right trade contract came along, I’d happily be a hybrid author. Considering that just a decade ago everyone seemed to be decrying the death of the book industry, it’s incredibly exciting to realise that it’s not just surviving but thriving. It may not look exactly like it used to, but as both an author and a reader I feel there’s great cause for optimism. •

The assistance of the Copyright Agency Limited’s Cultural Fund in providing funding for this article is gratefully acknowledged.