It’s a year this week since Russian president Vladimir Putin ordered the invasion of Ukraine in what he assumed would be a lightning takeover bolstering his prestige and Russia’s status. Instead, the attack turned into a diplomatic fiasco and a strategic car crash that inadvertently brought the world closer to nuclear disaster than at any time since the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. We could be one stray missile, a sharp turn of battlefield fortunes or a single miscalculation away from lighting the fuse to global disaster.

For NATO, therefore, policy has become risk management. On the one hand, it wants to prevent Ukraine from losing, force Russia to end the attack and deter future aggression in, for instance, the Baltic states. Besides hobbling Moscow with sanctions, this means giving Kyiv the intelligence information and weapons to kill thousands of invading troops and gut the Russian army. On the other hand, it doesn’t want to provoke a catastrophic reaction.

While US, French and British nuclear weapons add to the inherent danger of the crisis, only Russia has been flaunting its arsenal. Its thousands of nuclear warheads, divided between intercontinental range and shorter-range “tactical” weapons, are enough to reduce Europe to ruins, slaughter several million people and shatter civilisation. Even if the Kremlin had remained silent about them, these weapons are an existential menace.

But it has not stayed silent. President Putin, foreign minister Sergey Lavrov and the Russian security council’s Dmitry Medvedev allude to the potentially dire nuclear consequences of Western support of Kyiv. Further down the food chain, the state media continues its blood-curdling commentary, in some cases insanely calling for the obliteration of NATO countries.

We don’t know if the Kremlin is bluffing. But three factors seem to give substance to its threats: Putin’s character; the high stakes involved; and Russian military doctrine.

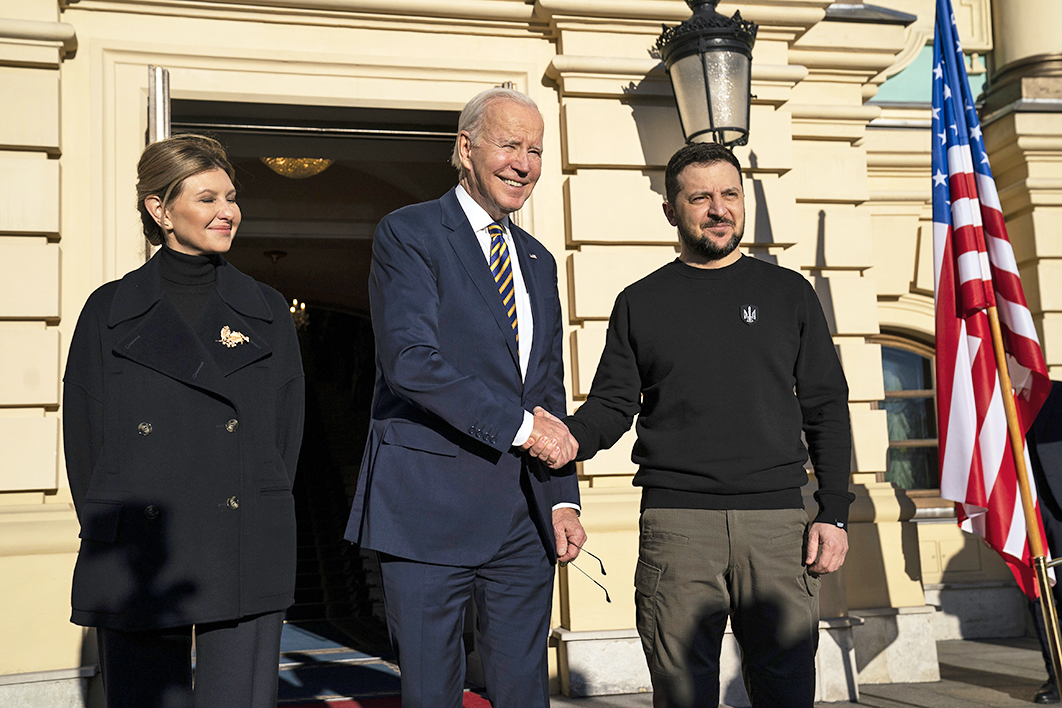

Many say the key to understanding the nuclear risk lies inside Putin’s head. Before he invaded Ukraine a year ago, observers considered him a ruthless but shrewd player of geopolitics; since then, though, he’s simply appeared reckless. And rather than Putin being the leader who has mastered the global chessboard, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy and US president Joe Biden seem to have Moscow’s measure.

So, we have a frustrated control freak with no conscience and a finger on the nuclear button. Perhaps he’s deploying the “mad man” card, carefully playing his hand to limit Western intervention? Or has he become a rash gambler?

Without a proper psychological assessment and a fly on the wall inside the Kremlin, it’s unclear how far a character assessment can take us. We don’t know how much authority Putin has over Russia’s nuclear forces, with reports saying he shares it with senior officials. And although he licensed the current spate of rabid nationalism, we don’t know how much he now controls it. Still, as far as we can tell, he continues to call the shots.

Another reason the nuclear threat appears credible is the high stakes involved. Russia’s status as a great power and Putin’s survival is said to hinge on victory, or at least avoiding defeat. There’s also an ideological aspect to this, with Putin and nationalist zealots arguing that the war represents a civilisational struggle between righteous Russianness and degenerate Western Satanism. This is just the sort of binary or absolutist framing suited to prepping for an apocalyptic conflict.

Finally, some experts argue Russian military doctrine adds weight to the nuclear threat. In particular, they say the idea of “escalate to de-escalate” gears Russian forces to respond to an imminent decisive defeat of its army, or to conventional air attacks on the Russian homeland, with a limited nuclear strike to compel enemies to back off. (This echoes Washington’s refusal to rule out nuclear first use, and NATO’s cold war strategy of flexible response, which encompassed the concept of nuclear warning shots.)

In other words, the Russian general staff has institutionalised a crossover between large-scale conventional war and scenarios for nuclear strikes. While this doesn’t make it automatic, the potential for escalation is baked into strategy. An extra twist is Moscow’s annexation of about one-fifth of Ukraine, suggesting the conquered regions are now considered part of the homeland and so covered by its nuclear deterrent.

Whatever its end point, the Kremlin’s nuclear threat has so far worked, at least to a degree. Fear of precipitating world war three is the main reason NATO ruled out imposing a no-fly zone over Ukraine, and it helps explain NATO’s initial reluctance to supply long-range artillery and tanks. Today, Western fear of escalation shows in the refusal to supply Kyiv with even longer-range artillery and combat aircraft.

In each case the West has been sensitive to Russia’s supposed “red lines.” NATO has even internalised them as an essential tool for crisis management. The principal red line here separates measures intended to aid Ukraine’s defence from those threatening Russian territory.

As conceptual tools go, red lines appear objective and clear. In practice, though, they have been more subjective and elastic. While there’s still a prohibition on direct NATO combat with Russian forces, everything else has become blurred. This is partly because the distinction between defensive and offensive weapons is largely artificial, depending as much on context as on technical attributes. Even the distinction between defensive and offensive operations can be problematic when the issue is reclaiming lost land.

This matter surfaced in the debate over the supply of tanks. Were the German-manufactured Leopards intended to prevent a Ukraine defeat while the country continued to bleed out, or to aid Ukraine’s victory and put an end to the war? And what would a victory look like?

Eleven months ago, many would have judged fighting the supposedly mighty Russian army to a draw along the current front line as equivalent to a Ukraine win. Today, most Western commentators say victory requires further embarrassing the humbled Russian army and recapturing the territory occupied since February 2022. Kyiv has set the bar higher: pushing the Russian army out of the land seized in 2014.

Hanging over all of this is the future of Crimea. Controversy over the peninsula is set to reshape the debate over red lines, not least in Washington. Kyiv and Moscow are both convinced of their historical and moral right to the place, but Ukraine’s legal claim is far stronger and would provide the basis for Western support of an offensive to expel Russian forces.

A solid legal case is not the same as sensible policy, however. Assuming it could be done, would retaking Crimea be worth a (say) one-in-ten chance of triggering a nuclear holocaust?

The answer is a matter of opinion. It’s interesting that the country most vulnerable to Russian nuclear forces — Ukraine — appears the least concerned. Kyiv is the most hawkish player in the debate about reclaiming Crimea and other lost territories; it seems, on the surface, prepared to pay any price and run any risk.

This is important because, while NATO and Ukrainian interests overlap, they’re not identical. Western commentators often forget to factor in autonomous Ukrainian decision-making, and assume that Kyiv will keep its strategy within guardrails established by outsiders. But while Kyiv has good reasons not to cross its international backers, the war is about Ukraine’s independence, not its subordination to Western interests.

Ukrainians don’t picture the conflict in geopolitical terms. They see what’s right in front of them: Putin’s trashing of their country’s sovereignty and dismissal of its national identity, his willingness to seize as much of their land as he can get away with, the millions of refugees, and the savagery of the Russian army and its mercenary associates. The resulting hatred is not conducive to a restrained response from Kyiv if it identifies an opening for an offensive that sends the occupying force into ignominious retreat. Throwing the Kremlin off balance could well become Kyiv’s aim, even if that disrupts Western ideas of escalation control.

Some people don’t see this as a problem. Social media is full of keyboard warriors wanting to pour weapons into Ukraine as though Russian nuclear weapons don’t exist. Even respected commentators advocate NATO going all-in, paying little regard to the potential nuclear consequences. Some experts advise facing down Putin’s nuclear blustering like we would a schoolyard bully. For these people, Russian huffing and puffing has run into diminishing returns, becoming little more than background noise.

NATO can’t afford to be so cavalier. The consequences of being wrong are too dreadful. So it’s intensely interested in scenarios showing how and when the nuclear threshold might be crossed. Start with a projected Ukrainian counteroffensive that overruns a large part of the Russian army on the border or employs air attacks to strike deep into Russia. This would lift the stakes and speed the pace of events. The resulting strategic adjustments could be hasty and prone to miscalculation, perhaps setting the scene for a limited Russian nuclear strike on Ukraine.

NATO might then respond with direct conventional military intervention. And, almost certainly, once the Kremlin had broken the nuclear taboo, America’s preparations for nuclear war would be ramped up. A different type of escalatory dynamic would pit Moscow against Washington in a starker form of brinkmanship.

Strategists on both sides think deterrence requires convincing the opponent that they won’t back down, that they’re prepared to climb the escalation ladder all the way to large-scale global nuclear war. Adding substance to the idea are elaborate plans matching individual warheads against specific targets. This is a surreal space in which potential casualties are counted in the millions and military officers are drilled in worst-case analysis.

Increased alert levels for Russian and American forces could thus become mutually reinforcing, intensifying fears of surprise attack and inadvertently creating pressure for massive pre-emptive strikes. Misunderstandings and accidents would become more dangerous, perhaps confronting decision-makers in Moscow and Washington with a kill-or-be-killed moment.

This is the apocalyptic picture Putin tries to leverage. But apart from some loose talk, there’s no evidence he actually wants to blow up the world. He probably has serious doubts about “escalate to de-escalate,” not least in terms of cost–benefit calculations. But even if he is, in his private moments, set against radical escalation, the conflict could take on a life of its own. The stresses of responding to pressing events on the ground or in the air above Russia might crowd out yesterday’s assessments. Whatever was in his mind could be altered by unfolding events that can be neither reliably predicted nor easily controlled. He might, at last, have to put up or shut up.

The recognition that the war could turn into a bigger catastrophe has obviously not paralysed the West. Apart from the domestic political price of abandoning Ukraine, NATO is concerned about the harm to global security if it fails to resist territorial expansion underpinned by nuclear threats — harm that includes exposing more countries to Russian, Chinese and North Korean aggression, a rush to proliferation, and the nightmare of normalising nuclear warfare.

During the cold war, Washington refused to intervene in Moscow’s sphere of influence when the Soviet army crushed anti-Russian movements in Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968). The reason for caution was fear of events spiralling into nuclear annihilation. Today, however, Washington is pushing the envelope by orchestrating military intervention inside the borders of the former Soviet Union, aiming to defeat Russia on its doorstep without tipping it over the edge. Only time will tell if it can master this necessary balancing act. •