Early in A Political Memoir, as Robert Manne evokes how “the post-Enlightenment dream of Germany as a home for Jews” so completely corrupted around his maternal grandparents in the 1930s, comes a phrase that resonates through the book — or at least did for me. What Otto and Frida Meyer faced, he writes, “was the ideologically conjured hostility of strangers and the opportunistic betrayal of former supposed friends.”

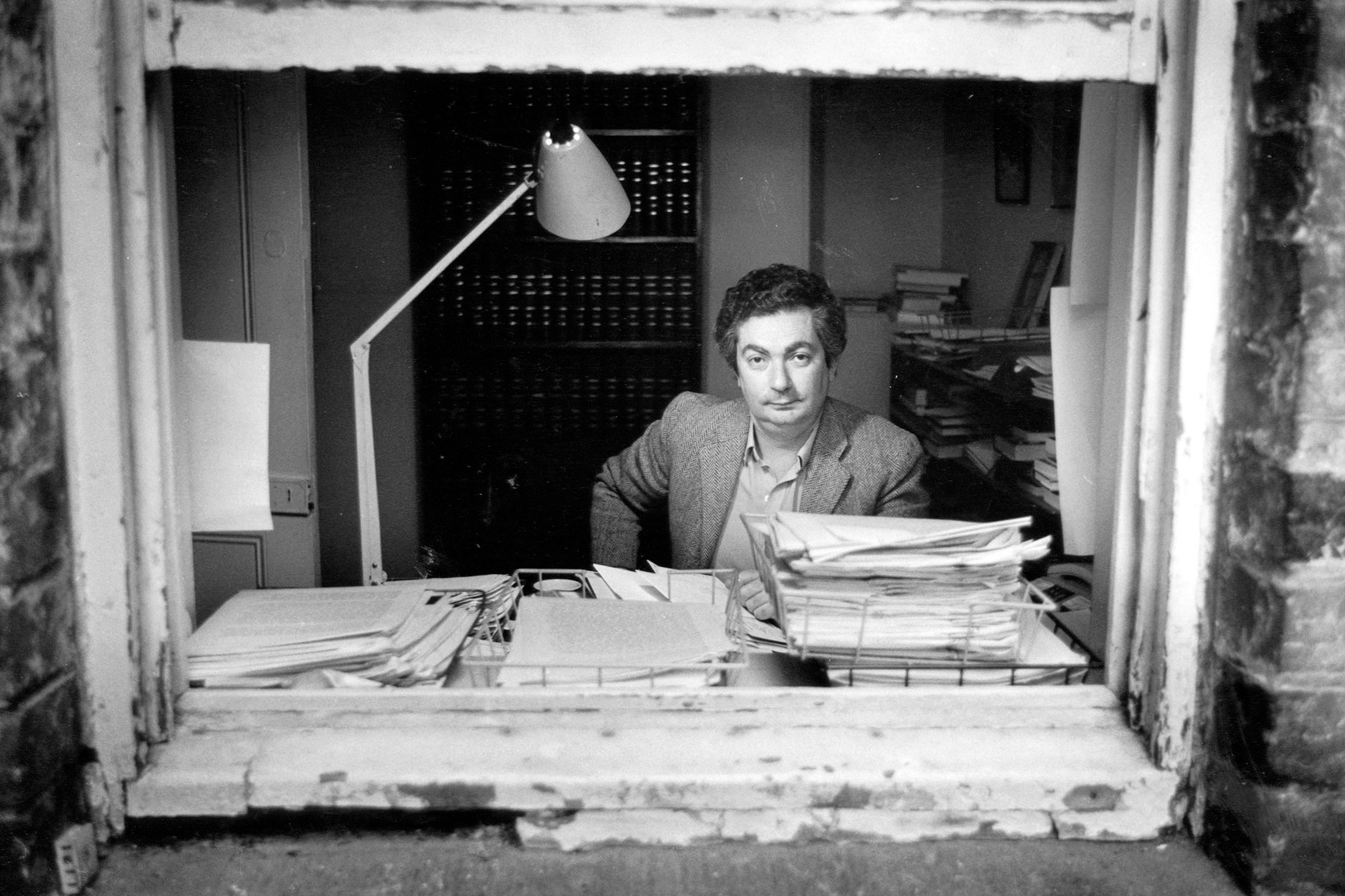

Like many other readers, I came to Manne’s reflections familiar with the outward focus of his life of “intellectual combat.” Over forty-plus years of unflagging engagement with public affairs he has exposed the pervasive influence of the twentieth century’s “political evil, the burden of our times — totalitarianism, genocide and war.” Manifest first in Nazism and Stalinism, the “murderous potential of ideas” has emerged in many variations, taking him into the public controversies and adversarial stances to which his subtitle alludes.

But this fleeting glimpse of the Meyers, both dead in 1942, she in the Lodz ghetto, he at Chelmo, has a different register. What would it have been like to be the subject of such intense hostility? In an account driven by certainties about his own his positions and those of his adversaries, he pauses at such a question: “I have no idea.”

Manne’s terms of “combat” are always well-parsed. Profoundly influenced by Hannah Arendt in this and much else, his sense of totalitarianism encompasses not only a regime or movement but the pervasive fragmentation that is interdependent with capacities for control and coercion in modern societies. Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt warned, can exist even as a temptation within ostensibly reformist aspirations — in the state’s tendency to reduce diversity to policy categories and in a social domain that can become complicit in potentially dehumanising and/or radicalising programs. These are the threats he has sought to expose, whether in the stark and diffuse Cold War politics of the 1970s–80s or faced with the “ideological extremism at the heart of the Australian neoliberal movement” from the 1990s onwards.

For the most part Manne has chosen to base this memoir on his many publications as accurate records of “what I believed at different times.” That emphasis on conviction is vital, and he insists that the printed record shows his “moral and political consistency” across those years and debates. Following his narrative is to be reminded of the depth and iterations of contests over who controls “culture” in Australia (from “the left” to Rupert Murdoch; from the new elites in expanding universities after the 1960s to the populists of the digital age) and of the forums central to those clashes, within which, as admirers including publisher Morry Schwartz have contended, he became the nation’s “loudest quiet voice.” Those with even a passing interest in Australian politics will be familiar with Manne’s positions. His “left, right, left” odyssey has made him one of our most recognised and perhaps anathematised public intellectuals.

There has always been a self-reflexivity in Manne’s writing, and his highly charged, personalised analyses of the “burden of our times” have seen “moral vanity” added to the faults his more hostile critics identify in his work. Yet when this memoir pulls back from what can sometimes seem an exercise in vindication, a different impression emerges — as it does in that early image of his grandparents. The outward focus on “evil” becomes a more inward, intimate reflection on the experience of loyalty and betrayal, informed by “my parents’ and my peoples’ history” but also by his own journey — his navigation of and part in the often corrosive tribalism of Australian political and intellectual wrangling.

The result, at least for me as I weighed my own uncertainties about how to “place” Manne, is a compelling if not fully resolved account of the experience and contexts of his commitment as well as of the fight for such causes.

Written after surgery for throat cancer in 2016 reduced his voice “to a whisper” and his “hunger” for political dispute dulled, A Political Memoir allowed Manne to see “clearly the decisions I made that shaped my political life.” Politics as a practice, an exercise in judgement, can seem for Manne (again influenced by Arendt) like his concept of “reason” — an aspiration towards action capable of rising above all that was encompassed by totalitarianism.

It was a calling that formed early. Outwardly it was there in his determination not to be drawn into “the funereal parade of yawn-enforcing facts” (as Kingsley Amis wrote in Lucky Jim) that academic work might become. After less-than-fulfilling postgraduate study of history at Oxford, Manne returned to Australia in 1974 determined to find ways of “influencing opinion not directly, in the daily cut and thrust of parliamentary politics, but for the most part indirectly and in the longer term.” Appointed a lecturer in politics at La Trobe University in 1974, he joined a cohort — John Hirst and Dennis Altman among them — who shared those aspirations. Inwardly, however, there were deeper roots.

Born in 1947, the child of refugees, Manne was “fascinated by small, apparently insignificant events that seemed to reveal relations of power.” He was intrigued by codes of class and sectarianism in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs and by forms of Anglo-Australian sentimentality that for a while offered a “crimson thread” of connection.

His father hoped to translate European elegance into Australian taste in return for acceptance “without discrimination.” In a treasured cardboard box Manne catches hints of his father’s voice: clippings of the many articles on music, design and international affairs Henry Manne wrote after arriving in Australia in 1939 reflecting what he valued and feared. But his son was too young to hear that voice before the writing suddenly ceased and Henry’s small custom furniture factory failed.

His mother Kate’s chronic illness meant that Manne often nursed her after his father’s sudden death in 1958 until hers in 1965, the year he finished school. He was grateful for the benevolent if austere ministry the Australian state provided to a widowed “invalid,” and would never fully subscribe to neoliberalism’s easy dismissal of “welfare.” That appreciation also informed his distrust of what (in closer step with the right) he characterised in the late 1980s as the divisiveness of “the radical multicultural left”: its threat to social cohesion, its “extreme insensitivity” to established values.

As Manne reflects, that box of clippings “affected my life.” It shaped a vocation “to continue what my father had been able, for a short time… to begin.” From his mother he “learned the meaning of fidelity to another and of unconditional love” — one element, perhaps, of the contempt for “sexual libertinism” that became part of his conservatism but perhaps also reflecting a vulnerability to “dissociation” from accepted values. Together these influences illuminate what can seem a disquiet within Manne’s calling to politics: the ambivalences of “belonging.”

This memoir delicately evokes a trust in close circles — of marriage, family and friendship. It similarly captures the importance of tight groups of intellectual solidarity “in which it was vital that both head and heart were fully engaged.” The “porosity” between the public discipline of the political and these more deeply affective relationships seems also to underpin one of Manne’s main intellectual reflexes: that of bearing witness, with all the weight that role has gained in a political culture which, since the 1960s, and not least in attempts to comprehend the Holocaust, has become so attuned to empathy, recognition and injury, and is framed by a new public space and an almost juristic imperative: who is to be believed; who is to be held accountable?

Yet witnesses can have an ambiguous, exacting role: they are to vouch for the truth of what happened more than explain it. While at least at one remove from “the event,” they are also involved. Their capacity to raise awareness of causes rests heavily on credibility and authenticity. Equally, for the public to reject their account is to confirm the failure of conscience.

Among the dominant emotional registers of this memoir is a “profound anger” — “radical astonishment” is the term Manne uses in his afterword — at the ease with which justifications can be manufactured for turning away from a distant other’s distress and for breaking more immediate relationships of trust in expediency. The “sickening shock” experienced by the Meyers and so many others, as Arendt insisted, reflected not so much an intention but the absence of thought among those who so readily betrayed a common humanity. Both were symptoms of totalitarianism, but the second is perhaps a more pervasive hidden legacy as atomised citizens in the wake of neoliberalism become more enmeshed in a kind of contest of distress. That is a transition this memoir compellingly describes.

The shock drove Manne’s determination to expose the suffering of Cambodians under Pol Pot in the 1970s. It continued in his dissection of the “culture wars” and the curated “denialism” that followed fast on the “heart-stopping” testimony of the “stolen generations” and of those seeking refuge from persecution in Indo-China, Central Asia and the Middle East. Finishing the book in the midst of the destruction of Gaza, it is there in his appreciation, “far too late,” that along with the lessons that must be learnt from the Holocaust (as “Never again’” shades in to “Never again, to us”) there is the perhaps even more fundamental challenge of climate change, given how “corporate interests and right-wing ideologues” have used the left–right struggle “to manufacture doubt” about testimony of science. More profoundly it is captured in visceral passages describing Manne’s sensations of destabilisation when confronted by incomprehensible views (such as, for example, the award of major literary prizes to Helen Demidenko’s antisemitic novel The Hand that Signed the Paper in 1992).

But it is also there in passages deeply enmeshed in the purposes served by such conflict. In 1985, as he recalls, he reached the peak of being “hated by the progressive intelligentsia” for his exposure of the Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett’s complicity with brutal North Korean and North Vietnamese regimes in the 1950s and 1960s. In 2004 he attracted equivalent scorn “from members of the right” for his coverage of the lies of the Howard government. In both instances Manne connects such pariah status to influence. However much he might now rail against such tribalism as “the most characteristic disease of intellectual discourse in our era,” he was often implicated in it.

In the background to all this is the boy with a “somewhat irrational and excessive” disposition to guilt and shame who is stimulated when, in Grade 3, his teacher writes “Segregation or Assimilation?” on the blackboard. This introduction to “the intellectual thrill and conceptual challenge posed by the opposition of two abstract words” offers an arresting image of “a strange child” finding an anchor in ideas, in paradigms of the paths a nation and its citizens might take, in the need to organise their world.

Without over-interpretation, I hope, or reductionism, I detected here a politics at once deeply personal but also generational and contextual. What the historian Odd Arne Westad has termed the “choice” of versions of modernity — central to and accentuated by Cold War conflicts but dependent on a range of other (if related) post-1945 transformations in state capacity and social imaginaries — intersects with a particular sense of displacement. The Cold War in Australia, as Manne’s close friend Martin Krygier has suggested, could seem at once elsewhere, urgent and existential, yet also parochial and bitterly contrarian here. Navigating between these polarities — given Manne and Krygier’s own connection back through their parents to those distant realities — was no easy matter, either within the Cold War’s frame or once it had passed.

A distinct intellectual style became part of that journey. Manne carefully recreates the impact of two mentors at the University of Melbourne during his undergraduate years from 1966 to 1969. He was drawn to “the coming together of thought and feeling in the making of a judgement” in the teaching of Vincent Buckley — a Leavisite approach with origins in the 1930s seeking to equip a generation with the “discrimination” to manage mass culture, adjusted to the 1960s and the all-too-smooth lure of being clever but complacent in what Buckley called a “jazzed up and internationalised” world. Buckley tested questions of honesty versus sincerity in ways that made for exacting self-scrutiny in literary criticism. But it was his sometimes frighteningly “dark anger” in translating such assessments into politics that, Manne recalls, “changed the trajectory of my political thought and thus my identity.”

And there was the “refined moral taste” Manne admired in Frank Knopfelmacher, a psychologist from Czechoslovakia via Palestine and Britain, whose passion for Cold War politics — for the imperative of seeing the truth, rendered here as “taste” — polarised the students he sought to engage in classes, at meetings and around cafe tables. Knopfelmacher was bold on macro-matters relating to the vulnerability of culture and institutions to ideological capture but less reliable, as Manne allows, on “micro-matters” that could drag those imperatives into corrosive personal assessments.

Still, Manne was inspired by his passion. So was Raimond Gaita, as a fellow student and Manne’s lasting and closest friend. Yet, as Gaita has recalled, few were so unequivocal in their admiration for Knopfelmacher or matched the intensity of Manne’s almost physical embrace of “the distinctive and tragic nature of political responsibility.”

Buckley and Knopfelmacher remained touchstones for Manne. They were part of the Quadrant circle — a grouping associated with the anti-communist magazine, founded in 1956, that provided Manne’s main affiliations well into the 1990s. Through those years, Manne says, he was an “instinctive and untheorised” conservative. Here, he is less than convincing. Effectively a generation younger than Quadrant’s main stalwarts, he became central to the strategic repositioning of the magazine.

In 1979 his exposé in Quadrant of genocide in Cambodia (“the first significant political article I had written”) focused mainly on the wilful, even “jaunty” distortions of that horror then characterising “the political culture of the postwar, university trained Australian intelligentsia” — a broad swipe, but exemplified in “Bob Connell, the youthful professor of sociology at Sydney University.” In 1985 his analysis for Quadrant of Burchett’s “treason” was similarly pitched against dissembling in the “postwar Asian history being taught in our universities.”

The memoir notes how Manne’s responses to these causes “enhanced my reputation with the most influential Australian anti-communists” and records Manne’s surprise at the readiness of academic colleagues to ostracise him after their publication. It doesn’t reproduce a rhetoric that might well have disturbed peers seemingly captured in this generalised conspiracy. Nor does it register that this was the Cold War of the late 1970s, intersecting with a decisive shift in economic paradigms: of a university sector facing standstill; Thatcher, soon Reagan, defining agendas; revolution in Iran and an invasion of Afghanistan bringing religious radicalism more centrally into calculations; and — yes — a conference on aid in Hobart that had no appetite for Manne on Cambodia but was also managing the increasingly fraught politics of humanitarianism (Bangladesh, Ethiopia, East Timor), the need for celebrity endorsement if there was to be any hope of donations, and the related need to shift emphasis away from raising global awareness towards more local and agency-based initiatives.

In this context, the broad-brush if personalised campaign against “the reigning left-wing orthodoxy of the intellectual class as a whole” (as Manne put it in a 1982 manifesto) was marking a clear departure from “the old and rather untroubled conservatism of the Menzies era” and rallying the “new conservatives” to (invoking Buckley and Knopfelmacher) “stay in the kitchen and put up with the heat.”

As another Quadrant contributor wrote in 1985, the pressing need was to “turn the language of outrage” back on the “New Class”: those pushing “multiculturalism, land rights, mining, welfare, conservation, non-competitive education… and so on.” It was time for “expertise” to be made more accountable to “the electorate”; “there is no middle ground.”

By 1989 Manne was integral to a move to arrest Quadrant’s perceived drift into the “mainstream” and take it back into its foundational fight against left-wing relativism. Among his first moves as editor, Manne offered another appeal to the faithful to contest the “new radical ideologies” — “feminism, gay liberationism, anti-nuclearism, extreme environmentalism, multiculturalism.” He concedes he is now “not proud” of this formulation, although, as we have seen, those terms were not only his at the time. Soon the “New Class” — at least among academics, perhaps less so among the technocrats — would look much less secure for reasons that had little to do with that older Cold War complacency.

For Manne, this was a period of remarkable consolidation. His Quadrant work brought attention from Sam Lipski, a young journalist who had pitched to Kerry Packer the idea of a television mini-series on the Petrov defection of 1954. Manne’s book from this project, The Petrov Affair, published in 1987, demolished the treasured Labor myth that Menzies as prime minister had manipulated the defection of a Soviet diplomat in 1954 with the intention of embarrassing opposition leader H.V. Evatt (some of whose staff were mentioned in documents the third secretary brought with him) and turning the imminent election from issues of social and economic policy (on which the government was vulnerable) into one held under the shadow of a global conflict made suddenly real and local.

The aftermath of the defection exacerbated tensions within the Labor Party, soon splitting it in ways reflecting “hard” and “soft” positions on communism but also marking other changes deeper within its ranks and constituency. Manne’s emphasis on failings in Evatt’s “character” as he handled that crisis fitted, however grudgingly, with a differently configured Labor government under Bob Hawke, keen to find closure with its own messy, internecine past. The book consolidated Manne’s academic claims as a sustained work of archival research: “my political enemies could no longer sneer at the uncredentialled Mr Manne.”

It also saw Manne invited into the inner sanctums of an older Australian “Establishment.” He was charmed by the unexpected generosity of Sir Charles Spry, the head of ASIO at the time of Petrov’s defection, when he was invited to Spry’s home and club. In 1987 he expressed deep indebtedness for Sir Charles’s “trust” in helping the “drama and the humour of the Affair… [come] alive for me,” for Evatt had emerged from his book with Spry’s help as a tragic fool. His memoir, however, confides that in those exchanges some subtle influence might have been sought over what he would write.

Once a respected but remote figure, Spry still needed to guard reputations: his ASIO, so confident in Cold War certainties, was being judged to have missed the beat on the changing character of insecurity within Australian society. More tellingly, Manne recalls the presence of Spry’s son on the margins of those discussions — and here it is not so much the “old” manners of conservatism that he detected but its new games and networks.

The son, Ian Spry QC, later edited the journal of one of the neoliberal think tanks emerging at that time, the Council of the National Interest. Manne notes him wearing a knitted cardigan, like “a country vicar from an Anthony Trollope novel” — an oddly precise observation until given meaning when Manne found himself in 1995, after a “large, supposedly private” dinner held by the Council, drawn into tests of loyalty and “integrity” surrounding allegations of sexual and other impropriety against “a senior Melbourne lawyer.” So many elements of Manne’s world, of belonging, were being challenged at this point. His writing subtly captures them.

Sir Charles, Manne judges, “was probably fortunate to have died” before his son became the protagonist in this scandal. But the closed circles within which an attempt was made to contain rumour and reputation (including, for Manne, meetings with evasive lawyers and pious notes on letterhead from exclusive private schools) was just one dimension of the codes through which such well-resourced “societies” (the scare quotes are Manne’s) were gaining their influence. He had found such networks “interesting” in the early 1980s, as they discreetly reached into his university circles. They offered confidences and alluring options (might he like a job as a staffer for senior Liberal politicians?). But already, inchoately, such insinuations sat uneasily with his sense of calling and propriety. Soon they would more overtly challenge both.

“The fine white wine” offered by Western Mining’s chief executive Hugh Morgan and other new patrons of Quadrant was rather different from the drink that fuelled Vincent Buckley’s rages — but back then the conspiracies were seen to be out there, in those existential registers of totalitarian contest. Now Manne was observing their calmer management from within, as part of a contest essentially over economic and political power that ranged from Liberal Party preselections to which writers he should and shouldn’t publish as editor and still how the intellectual elites should be brought to heel… but not from the alienated margins now, but from the corporate centre.

Manne emphasises his increasing discomfort with those moves: he regrets as “strained and inauthentic” his expected support for the Howard government as “editor of the country’s most important conservative magazine”; he draws attention to the qualifications he made to the observation that the “laissez faire right alone possesses self-confidence and social vision” to chart Australia’s future. Again, however, the record of causes should not set aside the rhetoric. Edging out of those roles and expectations was a nasty process — it brought Manne his own experience of betrayals. He left Quadrant in 1997, despairing at the “ideological fix” the journal was expected to provide to increasingly closed circles.

The speed of the transition is striking. One great value of this memoir is to take us back, and inside, this many-dimensioned shift.

One dimension is perhaps particularly revealing, and relevant to continuing alarm about Australia’s “public sphere.” The reception of The Petrov Affair meant Manne was taken up by newspaper editors looking for “opinion” and commentary in a media market already facing competition on several fronts, not least from commercial television current affairs (Packer introduced Sixty Minutes to Australia in 1979), with its own distinct style of mediating/sensationalising the news.

The first offer came from Eric Beecher, hoping to revive the Melbourne Herald. The Beecher experiment was shortlived: whatever sentimental attachment Rupert Murdoch had to his father’s first masthead soon gave way to market imperatives, those new political agendas and a preference for “opinion” pieces that drifted steadily towards self-referential, reputation-trading populism.

This was not Manne’s schtick, but became part of this new domain of commentarry. He began as a distinct inclusion in the Herald venture, erudite (one column noting how his childhood devotion to Geelong football club survived “even as I began to subject myself to the novels of Sartre and the films of Antonioni”), cosmopolitan (his perspective often infused with European perspectives) and avowedly “no stranger to controversy.”

As Manne notes, the files of his regular columns — moving from the Herald to the Age, the Sydney Morning Herald and then the Australian — enabled him to “reconstruct what I believed with exact and sometimes embarrassing accuracy” and also suggest the role served by such writing. The issues chart his intellectual trajectory, the common theme being the increasing divide between the “intelligentsia” and “ordinary Australians,” between the “pessimism” and “ideological” preoccupations of the former and the “existential” concerns of the latter, as citizens grew increasingly anxious about their economic security and place in the new politics of interests and identities.

If this was a role that gave Manne a vantage from which to increasingly appreciate John Howard’s dexterity in solving “the riddle of Australian politics” by turning cultural complexities into elite conspiracy, it was also one that saw him drawn into a kind of complementary process of backing contenders in the demeaning Labor leadership circus of the times.

This was hardly a high-point in the Australian “public sphere.” The “ordinary Australian” was a much-reduced figure from the readers Henry Manne had hoped to reach in the 1940s. It was certainly a narrowing of the “action” and independence of Manne’s own “political life.” As he recalls (with a strange absence of comment but an implicit recognition of his influence), Kevin Rudd was “open with me” in discreet meetings “about his intention to destroy Gillard.” And his columns made a supportive case: should it be Rudd in 2013, Gillard, the “lacklustre Stephen Smith” or “the quiet pigeon-fancier Greg Combet”?

As I hope is obvious, Manne’s memoir is invaluable on many counts, not least for its chronology of the many significant controversies in which he has been invested — storms that might quicky pass in words, and perhaps a little slower in reputations, but register deeper transitions. Taking a step back from them, however, suggests an important interdependence between causes and the forums in which they were debated.

From the politically pledged small journals of the 1970s to the newspaper opinion pages of the 1980s and then the interventions offered by independent publishers and blogs since the 1990s, Manne’s work can be mapped over the changing contours of the “public sphere” as it has itself been renegotiated over those years. Those contours can be related also to his own initially (or tactically) ambivalent positioning as “what came to be called a public intellectual.”

At the risk of being overly schematic, Manne rose quickly in — and almost picked up the baton for — a form of commentary already gesturing back to “the movements” that spanned the 1930s to the 1960s (including Quadrant’s synthesis of “Catholic traditionalists, rationalistic liberals, sceptical Andersonians, anti-communist social democrats”). He then served, with that contrition he now candidly offers, the move of commentary into the politics of the Howard years. He adapted well to a journalism that flourished — briefly — amid heightened attention to public accountability in the late 1980s before the market and editors turned towards a narrower domain of gotcha columnists and lifestyle features. Murdoch’s Australian came to exemplify a culture of rolling conflict, with a focus on ad hominem denigration in which Manne soon disproportionately figured as a target.

Perhaps, as Laura Tingle has observed, it was partly the loss of Australia’s old established binaries — of capital and labour, of faith and class — so beguiling to Manne as a child, that created the vacuum into which this new journalism rushed, with its next-generation columnists offering cavalier opinion and trading in social division. Manne, like a cohort of commentators (or “thinkers” as they tend to be termed) found sanctuary instead in the spaces provided by publishers such as Schwartz for longer-form conversations, determined to “talk back to power” about causes too easily captured by populist politics and vested interests, but also perhaps more circumscribed in their reach and market.

The profile of this group can be glimpsed in the contributors who joined him in hoping that Rudd in 2007 would end the alienation of “the nation’s critical intelligentsia” — in which he now evidently and confidently included himself. The common factor was a university affiliation, several years associated with non-government research or lobby groups, and a close engagement with policy analysis: this was the “social” domain Arendt had once seen as so residual. It was also the domain of the “expert” and “elites” that were — so the analysis ran — becoming more and more a target of resentment for “ordinary Australians.” The contrast with the settings that marked the ascendancy of Manne’s political life are suggestive: what are the relationships between these several levels of change as (referring back to his subtitle) the Cold War gives way to the Culture Wars?

Manne offers his memoir to those “who remember” the issues for which he has fought. This sense of a crusade has appeal. So does the shading of nostalgia: “you had to be there.” Many reviewers have welcomed the book precisely because (in Jonathan Green’s words) it prompts reflection on the loss of “an intellectual and institutional life that once propelled our public sphere.”

But remembering causes is not the same as appreciating what made them points of mobilisation, and why they mattered. As Gaita has observed in a telling choice of words, the “irrational hostility” to Manne is “hard to believe” for “many younger people who have matured intellectually after the Cold War.” “Irrational” carries a lot of weight here. Historian Tony Judt has suggested (admittedly of France, and earlier in the Cold War) that the kind of “quiet hysteria” in exchanges at that time, on both “sides,” and of the emphatically moralised quality of those debate, infused with acute self-justification and personal excoriation, should itself be a matter of historical curiosity — it itself and its legacies.

For those who were not there, however, that “kulturkampf” is of interest more in terms of what drew people into those movements and causes with such intensity rather than in rehearsing again the causes themselves. Equally, Jeremy Popkin has wondered why the autobiographical reflex among Australian historians has been peculiarly stamped with a tendency to use their personal stories to dramatise — even in the textures of their writing — a troubled relationship with the national project.

For Manne, of course, those personal stories plumb much deeper than the national project. “My future political life,” he writes, was shaped by the tension “between the calmness and civility of my country” and “the violence of the recent history of my family and people.” The causes that have drawn him in combat, countering “the burden of our times,” have been often sensitised by bearing witness to “the ideologically conjured hostility of strangers and the opportunistic betrayal of former supposed friends,” and certainly framed by a search for “tribes” in which he might belong. These themes make for a compelling narrative, and an acute perspective on Australian “political life” since the 1970s, even if (and perhaps, forgive the cliché, because) they are not always fully resolved. •

A Political Memoir: Intellectual Combat in the Cold War and the Culture Wars

By Robert Manne | La Trobe University Press | $45 | 498 pages