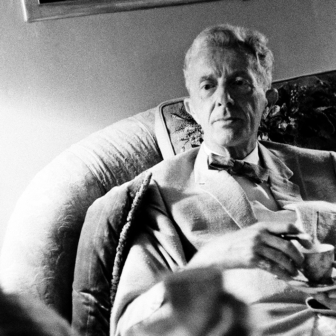

SOMALIA’S BEST-KNOWN contemporary novelist is Nuruddin Farah, who was born nearly sixty-four years ago in Baidoa, 250 kilometres inland from the capital, Mogadishu. Farah fled from Somalia in 1974 and now spends most of his time in Cape Town, about as far as you can get from Mogadishu without leaving Africa. After Siad Barre’s military regime was overthrown in 1991 he began making return visits to Somalia, including a trip in mid 2006 when he was invited – or at least he thought he’d been invited – to broker a deal between the main protagonists in the latest phase of the conflict that has gripped Somalia for nearly two decades.

Farah’s novel Links, published in 2005, is set in the Somali capital in the aftermath of the United States–led interventions in the early 1990s. These operations – Operation Restore Hope and its successor, UNISOM II – were a response to graphic coverage of the inter-clan warfare and famine that followed the fall of Barre’s government. The interventions were misconceived, came too late, and ended in failure.

By the time Links begins, the foreign forces have gone and control of the city is divided between two ruthless clan leaders. The main character, Jeebleh, has been away from the city for many years; in his memory Mogadishu is “orderly, clean, peaceable, a city with integrity and a life of its own, a lovely metropolis with beaches, cafes, restaurants, late-night movies.” It may have been poor, “but at least there was dignity to that poverty, and no one was in any hurry to plunder or destroy what they couldn’t have.”

He finds the city in ruins. Armed teenagers are killing for fun, refugees live in half-destroyed buildings and anything like normal life can only go on in fragments behind damaged walls. The clash between clans is profoundly affecting the lives of his friends and relatives. Farah describes the relationship between Jeebleh and his two half brothers, Caloosha and Bile, in this way:

“Although Calooshii-Cune – Caloosha for short – was Bile’s elder half brother, he and Jeebleh were of the same clan. Curious how the clan system worked: that two half brothers sharing a mother, like Caloosha and Bile, were considered not to be of the same clan family, because they had different fathers, and that Jeebleh, Bile’s closest friend, was deemed to be related, in blood terms, more to Caloosha, because the two were descended from the same mythic ancestor.”

Hostility between clans, sharpened by militant leaders and interference from outside, has fuelled the violence in Somalia over the past eighteen years. Unlike in most other parts of Africa, where ethnic differences have been key sources of tension, Somalia has one major ethnic group, ethnic Somalis, which accounts for the vast majority of the population of nearly eleven million. What helps to keep the tension alive is the fact that the geographic extent of the Somali people and the distribution of groups within the population bear no relationship to the current borders, which were drawn up after Italy colonised large parts of present-day Somalia and, twenty years later, Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) moved in from the west. Of the four largest clans, two still extend deep into neighbouring countries – over 250 kilometres into Kenya in one case and over 500 kilometres into Ethiopia in the other. Hardly any section of the Somali border corresponds to demographic reality.

Although the causes of the violence in Somalia are complex, the legacy of colonisation and the imposed borders do help to explain why the clan system continues to override a sense of national unity. Any peaceful change in the borders is extremely unlikely: Ethiopia already refuses to implement an adjudication on its border with its northern neighbour, Eritrea, and the African Union says that the existing borders must stay as they are, across the continent, in order to avoid opening or reopening dozens of conflicts.

SOMALIA appears sporadically in the western media, attracts intense coverage, and then drops out of sight again. The events surrounding Operation Restore Hope were typical: conceived as a response to widespread starvation, the intervention culminated in the Battle of Mogadishu, during which the bodies of US servicemen were dragged through the streets by local militia. The media coverage was intense. But the Americans left soon after, along with most of the press corps, leaving behind a bedraggled United Nations force.

Nearly a decade and a half later, in December 2006, the coverage ratcheted up again. Ethiopian forces had crossed into Somalia some time before, and now launched a full-scale operation – the International Crisis Group called it an invasion, the New York Times a “coordinated assault” – to install a body known as the Transitional Federal Government, or TFG, in Mogadishu. Throughout January, February and March 2007, the aftermath of the invasion – American strikes against alleged Islamic radicals, fighting in the capital, bombings – was described in detail in the western media, with generally critical commentary in Britain and more guarded coverage in the United States. But by April 2007 attention had shifted to other crises. Occasionally a bombing in Mogadishu was covered, but the overall impact of the Ethiopian invasion was largely left unreported.

Because conditions in Somalia are so dangerous, much Somalia-related diplomatic activity during the eighteen years since the country collapsed goes on in Nairobi. When I was there in April 2007, the events in Mogadishu were being dissected and debated. At the World Food Programme’s headquarters, the country director, Peter Goossens, told me that it was no longer possible to fly food into the city. “People who have been visiting Mogadishu for a long time say it is a lot worse than they’ve seen it,” he said, contrasting the violence at the time with the stability in the second half of 2006, when a coalition of groups known as the Islamic Courts Union controlled Mogadishu.

The role of the United States in these events, and especially Washington’s sudden decision to support Ethiopia’s intervention, was particularly contentious. As one diplomat told me, “People have sacrificed their home life, worked long hours, to deal with this situation. All sorts of motivations – personal, historical, national – are mixed together. It’s a very emotional issue.” (And not just emotional in Nairobi: a few days earlier the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette had published a tough editorial accusing Washington of working with “outlaw governments” – namely Ethiopia – in the Horn of Africa.) This was one of three western diplomats I spoke to about Somalia. One represented a former colonial power in north-east Africa, another a smaller European country, and the third was strongly pro-American. Each of them agreed to speak to me only on the condition that I did not reveal their names or nationalities. All three had a different perspective on the events leading up to Ethiopia’s decision to send troops to help the TFG force the Islamic Courts Union out of the capital.

The Islamic Courts Union had consolidated control over Mogadishu and neighbouring areas in the second half of 2006, bringing a degree of security and restoring social services. Backed by the Hawiye clan, it forced out the warlords who had controlled the city since the early 1990s and appeared to win significant support within the business community in the capital. But it imposed Islamic law, to varying extents in different areas, which inevitably led to fears in neighbouring countries and in Washington that a new Iran-style regime was in the making. For the TFG, based in Nuruddin Farah’s birthplace, Baidoa, the stability in the capital also challenged its own uncertain authority.

According to one of the European diplomats, fears about the rise of the Islamic courts were based on a misunderstanding of the character of Islam in Somalia. “Imagine a Leninist going to a Labour Party meeting in Britain and thinking they could easily impose their authority,” he said. “That’s what it’s like when Islamists try to impose their ideas on Somalis.” Faced with this resistance, the Islamists had been pursuing a gradualist strategy more in the tradition of the Fabian Society, he said, and they needed to be handled carefully by the United States, its allies and Somalia’s neighbours. The risk, now that the Courts had been routed, was that foreign Islamists would join in the fight against what is seen as an American-backed government. This is exactly what happened.

The presence of foreign Islamists in Somalia, regardless of their strategy and aims, was bound to generate a response from the Bush administration. In late 2006 Washington increased the pressure, alleging that the courts were sheltering al Qaeda figures, including activists who had been involved in the bombing of the US embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. When I questioned the pro-American diplomat on this point he said that there were “a few” recognised terrorists in southern Somalia. But he stressed that the Courts had taken over by force whereas the TFG was created by a recognised process. “Yes, the Courts achieved a lot,” he said, “but they pushed their agenda too far.”

Part of the difficulty for outsiders is the fact that the Islamic Courts Union was as much a coalition of convenience as a union. The authors of an April 2007 Royal Institute of International Affairs paper describe them as “a broad mosque” that brought together people “from moderate and extreme wings of political Islam.” While the United States and its regional allies focused on the radical elements, many local people were influenced by the on-the-ground benefits of the Courts in the second half of 2006.

Opinion was deeply divided within this broad mosque. As the pro-US diplomat said, hardline elements within the Courts had been pushing for more censorship of the media, more controls over non-government organisations, and even a ban on broadcasting the World Cup. But in each case the crackdowns were opposed and the hardliners were forced to relent. The diplomat conceded that this struggle within the Courts “could have led to a more moderate movement.”

According to the International Crisis Group, “Many Court officials were former civil servants, moderate Islamists or simply practising Muslims.” It was the Courts’ militant wing, al-Shabaab, that included members with links to al Qaeda. The mounting pressure on the Courts in late 2006, as Ethiopian troops filtered across the border, seemed to strengthening the radical elements.

The Transitional Federal Government is also disparate and divided. As one of the transitional federal institutions for Somalia, it was created in 2004 by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, a group of East African governments. It was designed to provide interim governance and create the groundwork for democratic elections. Inevitably, the makeup of the TFG reflects compromises among Somalia’s neighbours over how best to plan for peace – compromises in which Ethiopia seems to have got the upper hand. What it doesn’t reflect is a fully democratic process; instead, the leaders of the four main clans each selected sixty-one parliamentarians, topped up with thirty-one members from minority clans.

Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed, the president of the TFG between 2004 and 2008, is a former warlord from Somaliland, a de facto independent republic in northern Somalia, and had close relations with the Ethiopian government. Although the leadership of the TFG nominally included representatives of all the clans, during that period it was dominated by the Darod clan and eventually split along clan lines. The first speaker of parliament, a member of the Rahanweyn clan, was sacked by parliament for attempting to set up negotiations between the Courts and the TFG. It was President Yusuf’s relations with Ethiopia, along with the brutality of Ethiopian troops, that turned Somalis against the TFG.

“In an uncomfortably familiar pattern,” wrote Cedric Barnes and Harun Hassan in the Royal Institute of International Affairs paper, “genuine multilateral concern to support the reconstruction and rehabilitation of Somalia has been hijacked by [the] unilateral actions of other actors – especially Ethiopia and the United States – following their own foreign policy agendas.” As the distinguished historian of Somalia, Ioan Lewis, puts it, “the essentially domestic dispute over the TFG’s legitimacy was reconfigured in terms of the US ‘war on terror.’”

According to Jonathan Stevenson, a long-time observer of Somali affairs who teaches at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, once the Ethiopians had entered Mogadishu the United States failed to capitalise on the few weeks of quiet. “I think US support for the Ethiopian intervention would have been defensible had there been robust US diplomatic follow-up with an eye towards co-opting the Islamists by giving them a legitimate political role,” he told me. “That, however, has not happened, and the United States’ reliance on Ethiopian military coercion to stabilise Somalia is shortsighted and rash.”

“The Transitional Federal Government is simply not trusted by the populace,” wrote Barnes and Hassan. “Nor does it represent the powerful interest groups in Mogadishu. Controlling a disgruntled capital, let alone the entire southern region, has defeated many previous coalitions both more competent and more locally popular than Abdullahi Yusuf’s government.”

Unfortunately Washington’s misjudgements date back further than its decision to support Ethiopia’s action. Until late 2006 its support for the transitional institutions was tepid; instead, it was covertly funding warlords and their ill-disciplined militias in a doomed attempt to keep the Courts at bay. According to interviews conducted by John Prendergast and Colin Thomas-Jensen from the International Crisis Group, these warlords were receiving “about $150,000 a month” from the Bush administration. “In contrast,” they write, “the United States contributed only $250,000 to the $10 million peace process that led to the formation of the TFG, and the United States gives far less humanitarian assistance to Somalia than to other countries in the region.” For one of the European diplomats, a supporter of the TFG, it was a bitter paradox: “The US funded warlords in Mogadishu and delivered the city to the Islamic Courts.”

Although it had opposed a full-scale Ethiopian intervention, the United States suddenly changed policy in late 2006. In early December the Courts signed an agreement with the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, pledging to respect existing borders and the sovereignty of neighbouring countries and condemning all acts of terrorism; at the same time, the Courts intensified their attacks on the TFG and its protective force of Ethiopians troops. Ethiopia responded with increased pressure. In mid December, US Assistant Secretary of State for Africa, Jendayi Frazer, turned up the heat another notch when she said, “The Council of Islamic Courts is now controlled by al Qaeda cell individuals, East Africa al Qaeda cell individuals. The top layer of the court are extremists. They are terrorists.” Scarcely anyone who knows anything about Somalia agreed with this characterisation of the Courts’ leadership at that time.

According to the International Crisis Group, Frazer’s comments were a “tacit green light for Ethiopia to invade Somalia,” and there were important reasons why Ethiopia was happy to oblige. A series of belligerent statements by a group of Court leaders had given new life to the long-running border dispute with Somalia, and Ethiopia – despite its obvious military superiority – was anxious to forestall any irredentist claims. Another border dispute, between Ethiopia and Eritrea, was also feeding into the conflict, with the Eritreans providing military assistance to the Courts in order to put pressure on Ethiopia.

Perhaps most significantly of all, this ally of the United States was mired in conflict at home. After a promising start, the government of Prime Minister Miles Zenawi had become increasingly repressive. Opposition protests at alleged election fraud by the government in 2005 were met with shootings – forty-six people were estimated to have died – and detentions. The government in Addis Ababa undoubtedly calculated that taking an active part in the war on terror would help take the heat off its own human rights abuses. As well as intervening in Somalia, from January 2007 Ethiopia interrogated Somalis “rendered” from Kenya in an operation apparently mounted jointly by the Kenyan government and the United States.

Once Mogadishu fell to the TFG and the Ethiopians the news from Somalia was patchy. Very few western journalists went into the capital and those who did usually stayed only a few days. A surge in violence between mid March and late April 2007 killed an estimated 1670 people. In May the UN High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that the fighting between Ethiopian forces and the remnants of the Courts had created a refugee population of over 320,000; by the end of the year the estimated displaced population, within Somalia and in neighbouring countries, was one million.

In September 2007 Islamist and other opposition groups – including former senior TFG members – formed the Alliance for the Re-Liberation of Somalia. The alliance split in mid 2008, with one group favouring talks with the TFG and the other favouring guerrilla action; both were led by former Courts Union leaders. As Xan Rice reported in Inside Story in May, one of those leaders, Sheikh Sharif Ahmed, now heads the TFG, and the other, Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys, leads the insurgency.

Apart from the civilian deaths, the impact of the fighting was enormous. By the second half of 2008 the UN Food and Agriculture Organization was describing Somalia as an “unfolding humanitarian disaster.” According to an analysis by the FAO’s Food Security Analysis Unit, “Rates of malnutrition in most of southern and central Somalia are above emergency threshold levels of 15 percent and in many areas greater than 20 percent and increasing,” with the continuing conflict a significant contributing factor. In September the UN High Commissioner for Refugees reported that thousands were leaving Mogadishu because of the fighting.

According to Daniela Kroslak and Andrew Stroehlein of the International Crisis Group, the Ethiopian presence and the US bombings of suspected militant hideouts “set in motion a chain of events that in mid-2008 culminated in the recapture of much of the country’s south by the hardline Islamist insurgent group, Al-Shabaab. They used the Ethiopian presence to rally support from and recruit amongst those marginalised by the transitional government, and they radicalised the Islamist movement.” The evidence suggests that the recruitment included radicals from other Muslim countries and from the west.

There’s no way of knowing what would have happened if the US administration hadn’t given Ethiopia the go-ahead to invade. The Islamic Courts Union might have continued to consolidate control and security, with intermittent internal battles over the extent and character of sharia law, or it might have become more oppressive, or it might have fallen apart. But we do know what happened after the Courts were overthrown, and it’s not an encouraging advertisement for western interference. Six weeks ago two International Crisis Group analysts reported that “the scale and ferocity of the latest fighting between the transitional government and the hard-line Islamist factions opposed to it is unprecedented, even by Somalia’s grim and bloody standards.” Ethiopian troops formally withdrew from Somalia by mid January this year, although reports suggest a number of them are still inside the border.

The most critical failure of the western-backed process that eventually brought the TFG to Mogadishu, according to Ioan Lewis, was the failure to “insist on the parties actually trying to make peace before trying to make a government. This was the usual denial of the importance of proceeding on a bottom-up basis, with the development of governance as a result of satisfactory peace agreements at the grass roots… These repeated errors probably wasted billions of dollars and caused correspondingly enormous human suffering.”

IN JULY 2006, before these events took place, Nuruddin Farah flew to Mogadishu to attempt to broker talks between the Islamic Courts Union and the TFG. He had been contacted in Cape Town by an acquaintance in the executive directorate of the Courts who wanted him to “carry fire,” as the Somali expression goes, between Mogadishu and the TFG headquarters in Baidoa. According to the acquaintance, the Courts were offering to let the TFG move to Mogadishu and engage in negotiations.

Later, Farah described his response in the New York Times:

“Why me?” I asked.

“Because the ICU admires your opposition to Ethiopia, Somalia’s arch-enemy, and because of your avowed interest in peace,” he replied.

And, truth be told, I admired some of what the Islamists had accomplished… Like many Somalis, though, I also had my reservations about them. Even though almost all Somalis are Muslim, very few embrace the union’s fervent brand of faith: the group supports Shariah law and it treats the federal charter, which is secular, with disdain. Then there was the matter of clan rivalry, which hinted that devotion might be masking politics: the top Islamists belonged to the clans known to be antagonistic to the president’s clan.

Of course, my feelings about the transitional government were also ambivalent…

Farah’s account of his meetings with leaders of the Courts, who seemed to have forgotten or abandoned the idea of negotiations with the TFG, and with President Yusuf, who was no more cooperative, echoed the strangely shifting world of his novel Links. He hoped that this account of his visit to Somalia “might help explain in concrete – and human – terms why the conflict has become so difficult to solve and” – he wrote presciently – “why the transitional government, backed by the United States and with the support of Ethiopia, is probably doomed to fail.”

Both sides must compromise, he says. “Most Somalis believe that the Islamists deserve a place at the table; they have been disempowered through invasion by an occupying force, which must withdraw, the sooner the better.” Although negotiations will not be easy, “Somalis must consider the alternative: the violence will continue and the rest of the world will continue to use land as a playground for intervention.” •