In recent years, as a historian of Australia, I’ve found that the book people most wanted to talk to me about is Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu. Many readers speak of it with a sense of astonishment and revelation; they often tell me that Pascoe’s book completely changed their understanding of Australian history. They did not previously understand the sophistication of Aboriginal land management; they had not previously felt the full injustice of European conquest and dispossession. I’m grateful for a book that has so enlivened the engagement of Australians with their country’s history.

To some, Dark Emu seemed to come out of nowhere, but Pascoe’s latest book, Salt: Selected Stories and Essays, helps us to see how it grew from the author’s life experience and earlier storytelling. I’ve been a follower of his work since the early 1980s, when I read his fiction and subscribed to the literary magazine he edited and published with Lyn Harwood, Australian Short Stories. When Dark Emu was published in 2014, Bruce became a household name and many readers encountered him for the first time. One of the pleasures of Salt is that it weaves his earlier fiction writing together with his now-celebrated nonfiction. We meet — or rediscover — the pre–Dark Emu Pascoe, and we’re reminded that this powerful voice itself has a history.

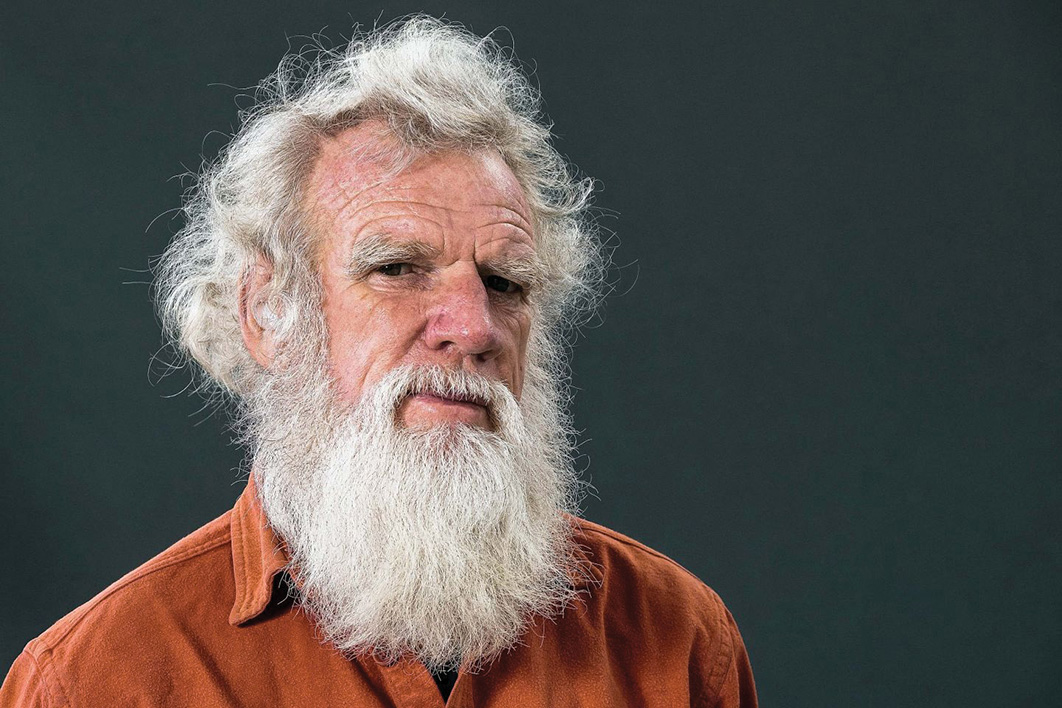

Pascoe is a writer but also a performer, an orator, a dedicated storyteller in the old style. I’ve sat with Bruce on a stage and found myself captivated by his careful, humble manner of speaking and gruff bush charm; he has a natural charisma and a mischievous wit. Earlier this year I was in a university lecture hall packed with hundreds of young people who had come out on a dark winter night to listen to the author of Dark Emu, and they were enthralled. You could have heard a pin drop. At the end of the speech the crowd erupted in an ovation for several minutes. Whatever Bruce Pascoe is saying, Australians clearly want to hear it now. And he has responded generously to the call, touring the continent tirelessly these past few years, accepting invitations to speak to audiences of all kinds in both city and bush. Apparently indefatigable in his early seventies, he reminds us of the enduring power of book and speech in the digital age.

In Salt he tells again and again of his realisation and dismay that Aboriginal history has been so systematically left out of Australian history. He discerns, as did John Mulvaney in the 1950s, W.E.H. Stanner in the 1960s and Judith Wright, Bernard Smith and Henry Reynolds in the 1970s, a wilful blindness, a Great Australian Silence, a complacent denialism about Aboriginal achievement. It is so persistent and embedded that it seems we have to keep rediscovering it, as if for the first time. Pascoe, a university graduate and schoolteacher, rails against the history he was taught and the texts he studied; his cry of betrayal is akin to Reynolds’s question (and book title), Why Weren’t We Told? (1999). There is an eloquent ire that informs Dark Emu and it suffuses Pascoe’s speaking and writing with the passion of a preacher.

Side by side with the public story of betrayal and revelation about Aboriginal history is Pascoe’s own journey into his Indigenous identity. Recently Andrew Bolt and Quadrant attacked Pascoe’s identification as a Bunurong, Tasmanian and Yuin man, wielding family trees like weapons. But Pascoe has long written with honesty and humility about what it means to be a pale-skinned Australian who has come to identify as Aboriginal: the forgotten branches of the family tree, the past conversations that suddenly make sense, the renewed connections with community.

“My insight into Aboriginal Australia is as abbreviated as my heritage has allowed,” he wrote in 2012. “It is as if I have been led at night to a hill overlooking country I have never seen.” In another essay in Salt he accepts scrutiny of his identity, reflecting that “clinical analysis of genes says I’m more Cornish than Koori.” But he explores his connection in a whole book about Aboriginal heritage, identity and belonging called Convincing Ground: Learning to Fall in Love with Your Country (2007). There he analyses the “suffusion of Aboriginal genes into the white population,” the identity of “people of broken and distant heritage like me” and how that “trace of blood doesn’t mean much unless you want it to.” Pascoe’s personal discoveries illuminate his investigations of the nation’s past.

The epigraph at the beginning of Convincing Ground reads: “This is not a history, it’s an incitement.” Dark Emu has gained traction from the self-professed marginality of its author and the impression that Pascoe’s revelations are also the nation’s. Kaz Cooke welcomed the book as “an elegant act of defiance,” and some of its power does come from being oppositional. Dark Emu has certainly reached new readers and awakened people, and the book has a strong analytical emphasis that I will soon address.

But what interests me here is the sense that Pascoe has had to fight against the grain of Australian historical scholarship to make his case. This is an angle that the media understandably loves. For example, Richard Guilliatt’s fine recent portrait of Pascoe in the Australian is titled “Turning History on Its Head” and promises to show how “academic conflict accidentally turned Bruce Pascoe into our most influential Indigenous historian.” It begins by describing Pascoe’s “long-running conflict with academia” and explains how one such confrontation over a cup of tea spurred him to write Dark Emu.

Disagreement is frequently a provocation of good books. But the implication here is that Pascoe’s crusade has been lonely and resisted. In Salt, he tells of “senior historians” who told him that “every primary document in the Australian history trove had been thoroughly examined; there was nothing new to be discovered.” I don’t believe any historian could believe or say such a thing; it would be a repudiation of their craft. My point is that the blindnesses and complacencies that Pascoe rails against are the same silences and lies that Australian historians have been collaboratively challenging for decades now. It’s a job that will never finish. Pascoe is primarily bridling at an older form of history, the history he learnt at school and university fifty years ago.

We could tell an alternative story of revelation, one that is more complex and collective. It would portray a collaborative political and intellectual endeavour across more than half a century, a concerted scholarly quest by black and white Australians to dismantle the Great Australian Silence. For the Silence itself has a tenacious history: it tightened its grip on the narratives of the emerging nation in the late nineteenth century, drawing a veil across frontier violence and underpinning the poetics and politics of White Australia. It was a great forgetting that was made up not only of silence but also of white noise. A cacophony of national history-making overwhelmed Indigenous testimony and the “whisperings” in settlers’ hearts, and it hardened into denialism — denial of the depth of Aboriginal history, denial of Indigenous sovereignty and land management, and denial of bloody warfare on Australian soil. The cult of sacrifice in overseas war — the Anzac legend — was essential to the denial of war at home.

Denialism persists today in culture and politics, as we see daily. But scholarship began to confront and overturn it from the 1960s as archaeologists, anthropologists and historians — increasingly working with Indigenous scholars and communities — worked their way into the traumatic oral testimony, the records of colonial conquest and bureaucracy, and the deep archive of the earth. It was — and continues to be — a protracted revolution in understanding, always challenged by reactionary denialism. Bruce Pascoe’s work is a further, marvellous elaboration of this great revolution in understanding the history of this country.

Pascoe does go some way towards acknowledging this modern scholarly context, for Dark Emu is thick with reportage and quotation, drawing on nineteenth-century sources and also citing the work of scholars such as Norman Tindale, Harry Allen, John Blay, Beth Gott, Jeannette Hope, Tim Allen, Rupert Gerritsen, Bill Gammage, Rhys Jones, Jim Bowler, Tim Flannery, Ian McNiven, Dick Kimber, Peter Latz, Deborah Rose, Harry Lourandos, Lynette Russell, Paul Memmott and Eric Rolls. He might have added the likes of Sylvia Hallam, Marcia Langton, Bill Jackson, Stephen Pyne, John Mulvaney and Isabel McBryde. But no account is given of how these historical insights have developed collectively over many decades to overturn earlier understandings. This inspiring story has been downplayed in Dark Emu.

What is novel about Pascoe’s work — and also surprisingly old-fashioned — is his explicit, analytical emphasis on the idea of agriculture. Aboriginal peoples, he argues, were farmers and bakers, the world’s first; they accumulated surpluses and lived in villages; they gathered seeds and harvested crops. Pascoe is consciously using the proud words the invaders used about themselves, words that justified dispossession — farming, villages, crops — and here he finds them in colonial descriptions of the original inhabitants of Australia, who he is keen to show were not “mere hunter-gatherers.” This is meant to be provocative and it is. With these words Pascoe detonates a primary European rationale for the conquest of Australia. The myth of “nomadism” was blown away by an earlier generation of scholars, as was the idea of “terra nullius”; then terms such as “hunter-gatherer” or “agriculturist” came to be seen as simplifying. But Pascoe wants to revive those categories triumphantly: Aboriginal peoples, he argues, were farmers.

This argument really matters in the history of Australia. It mattered from the moment the newcomers arrived and it still matters today — witness the recent conservative attacks on Pascoe and the critique of his work by those behind the website “Dark Emu Exposed,” who, significantly, self-identify as “a collective of Quiet Australians.” Agriculture is at the front line of the ideological war about the British colonisation of Australia. As literary historian Tony Hughes-d’Aeth has argued, “agriculture in Australia is a religion — it is as much a religion as it is an industry.” That’s why Pascoe has taken it on, digging out mentions of Aboriginal hayricks and stooks, crops and villages from the journals and diaries of explorers and colonists, no less, the very “sources upon which Australia’s idea of history is based,” as he puts it. Pascoe thus draws his evidence from the words of the legendary “firsts” in white history-making and shows how they saw more than we knew and sometimes more than they knew themselves.

This revisionary work is, I think, vital. We don’t understand enough about how Aboriginal peoples used and honoured this land for millennia. In spite of half a century of eloquent activism and scholarship, most Australians still grossly underestimate the sophistication of Indigenous culture, technology and governance. The popular embrace of Pascoe’s work suggests that many are keen to learn.

And these early witness accounts of how Aboriginal peoples managed the land are precious and fascinating. They invite a subtle reading, a cultural history that is attentive to both sides of the frontier. When Thomas Mitchell or Charles Sturt identified “hayricks” and “stooks,” their imperial eyes were observing features that they did not expect to see in the land of the “savage” — and they were also using the language of their own English rural culture to evoke the landscape of home, which they missed and hoped one day to remake in this strange land. There is prejudice, surprise and nostalgia distilled in these words. They deserve our close attention and open-minded analysis.

I understand why Pascoe has deployed the template of agriculture. He is turning a political tool of oppression and disdain into a case for dignity and respect. Archaeologist Rhys Jones did the same thing in 1969 when he coined the term “fire-stick farming.” It was a brilliant provocation and remains a foundational insight. But I think it’s a mistake to treat the concept of agriculture as a timeless, stable, universal and preordained template, to apply a European hierarchical metaphor, an imperial measure of civilisation, to societies that defy imported classifications. One of the great insights delivered by that half-century of scholarship is that Aboriginal societies produced a civilisation quite unlike any other, one uniquely adapted to Australian elements and ecosystems.

Pascoe often over-reads the sources — and for what purpose? To prove that Aboriginal peoples were like Europeans? Dark Emu is too much in thrall to a discredited evolutionary view of economic stages, a danger that Pascoe himself acknowledges in the book: “We have to be careful that we are not deciding on markers of civilisation simply because that is the historical path followed by Western civilisations.” Not only does this risk simplifying the surprising ingenuity and flexibility of Aboriginal economies; it also plays into the hands of conservative critics who are always ready to mobilise centuries of stereotypes about “Stone Age nomads.”

Two scholars are especially acknowledged by Pascoe in making his argument about agriculture. One is Rupert Gerritsen, whose book Australia and the Origins of Agriculture was published in 2008, and the other is Bill Gammage, author of The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia, a bestselling history of Aboriginal land management published in 2011. Gerritsen’s work, richly referenced, reminds us how long the debate about foragers or farmers has been going on in the scholarly literature, and he often draws on the same evidence as Pascoe (as Bruce acknowledges). Gammage’s book won wide acclaim and a popular readership but also drew criticism, especially from ecologists and archaeologists.

Pascoe and Gammage are often cited as making a similar argument, and they do both tend to homogenise the diversity of Aboriginal societies, ecologies and histories in their quest for a national saga. But their books are distinct in important and interesting ways. For example, Gammage argues that Aboriginal peoples “farmed in 1788, but were not farmers. These are not the same: one is an activity, the other a lifestyle.” He persists with careful distinctions: “Many people did live in villages, but most only when harvesting”; “they did not stay in their houses or by their crops”; “they lived comfortably where white Australians cannot.” Different Aboriginal societies used a range of practices throughout Australia, cultivating a wide variety of ecologies. And when Europeans brought their version of agriculture to Australian shores, it often didn’t work — and it’s in retreat in many regions today. The Indigenous alternative — in all its many forms — was grounded in a knowledge of Country. A strong dimension of Dark Emu’s popular appeal is the practical inspiration it offers for caring for the land and cultivating native perennial plants; Pascoe has himself invested in the bush foods industry.

A scholar’s reaction to Dark Emu can therefore be mixed. First there is surprise that large sections of the reading public are still unaware of scholarship that has been brewing since the 1950s, but there is also gratitude for a book and a voice that awakens people. There is concern that archaic evolutionary hierarchies should be revived just when we thought that such a northern-hemisphere mode of thinking had been transcended in Australia. There is criticism of hyperbole and of evidence being simplified or overblown. And there is admiration for the sheer bravura of a man on a mission, a gifted Australian writer whose work has struck a chord with the public and whose words — written and spoken — are inspiring and empowering Australians, black and white. The new book, Salt, reminds us of the storytelling muscle, poetic depth and moral seriousness of Bruce Pascoe, and of his role as a public intellectual who has wrestled for decades with the idea of Australia. •