In what field of human endeavour does Mexico rank above the United States? Senegal above Japan? Nigeria above Austria? In what international forum do the peoples of Hong Kong, New Caledonia and Palestine all have equal status with the great centres of power? What cultural form, despite the greed and folly of its highest officials, is a source of joy to literally billions of people, both as elite spectacle and inclusive community activity?

These musings came to me a year ago while I was watching a Women’s Football World Cup match played here in Australia. The local team, the Matildas, got a lot of attention, which was wonderful and well-deserved, but this part of the tournament didn’t involve them. Rather, it was Morocco that gripped my attention. Against all expectations, its team had made it to the last sixteen and was playing a knockout match against France.

As is the way with most sports commentary, the historical, political and social significance of the match was… well, not exactly ignored — you have to be aware of something to ignore it. But this was a momentous occasion. Here was a group of women from a Muslim kingdom in North Africa playing football on the world stage. They were meeting, on equal terms, their nation’s former colonial master: a First World nation, vastly richer, with almost twice the population.

Football is the most ironic of games. An invention of Britain at the height of its imperial age, it is also the most thoroughly decolonised of all major sports. Wealthy nations have an advantage, sure, but football is more nearly a meritocracy than almost any other human activity.

Including, I realised, literature.

As the game unfolded — France won easily, four–nil — it occurred to me that I had never read a book by a Moroccan author.

I could not even name a Moroccan writer. Not one.

And yet this is a nation of thirty-seven million people, with a history stretching back to antiquity and a rich culture. True, it has an oppressive government, but it also has a long history of struggle against oppression. There must be a literature there, even if some of it has been written in exile.

As someone who loves literature and prides himself on reading widely, this was a bit of a shock to me. And it got worse. I looked at other nations competing in the World Cup: Brazil, Costa Rica, Zambia, South Korea. I hadn’t read a single book by a writer from any one of them.

Hoping for inspiration I went to one of those huge “1001 books you must …” tomes, which claimed to be “a comprehensive reference source chronicling the history of the novel.” And I went through the whole damn thing, hunting for diversity with growing despair. There were 233 works by authors born in the United States, 218 from England, and another 128 from elsewhere in the United Kingdom or the Irish Republic. Non-Anglophone Europe provided 203 novels. The whole of Africa: twenty-four (eleven of them by J.M. Coetzee, a white South African who lives in Australia). The whole of Asia: thirty (not one from China). Latin America, including Mexico: fifteen. Nine from the Caribbean. From Oceania, excluding New Zealand: nothing.

When you step back and look at it, literature — that progressive humanist art accused by conservative culture warriors of being anarchically woke — is colonialist to its bootstraps. Writers, mostly white, mostly English-speaking, mostly writing in English, are almost all published by a small number of companies headquartered in London or New York.

Surely, I thought, literature can and should be as inclusive as football.

Every people has a story

And so began my strange quest: to make my reading as inclusive as the World Game. I would read a work of literature produced by every people that plays international football. (With some reluctance, I decided to use men’s football, because many nations don’t field a women’s team, at least not yet.)

When I looked, the FIFA world rankings listed 208 men’s teams. Brazil was at the top, and the list wound its way — via every continent bar Antarctica — down to the last-placed team, the US Virgin Islands. If you haven’t heard of it, the US Virgin Islands is an American colony-not-a-colony of 120,000 people in the Caribbean. Historically, the islands were a Danish slaving entrepot, then a colony, which was sold (yes, sold) to the United States in 1917. Cup of imperialism, anyone?

The presence of those islands on the list reveals an admirable thing about FIFA: you don’t need to be a sovereign nation to play. All manner of colonies, dependencies and nations-not-universally-recognised make the grade: the Faroe Islands, Palestine, Curaçao, Hong Kong, Wales, Guam — the list goes on.

I printed out the FIFA rankings and pasted the list into the front of a large notebook. Then I added the project’s motto: “Every people has a story which deserves to be heard. And almost every people has a football team. Simple, really.”

I resolved that while the literary form was unimportant — novels, short stories, memoirs and poetry; all were acceptable — the one hard rule was that the book had to be written by someone from the people in question. No travel writing. No reportage by foreign correspondents. No histories by outsiders. I wanted sharp-edged writing by, for and about a people. The Nigerian writer Chigozie Obioma talks of “the sadness of writing about Nigeria… Nigeria riles me, wounds me, and heals me at the same time. I love it entirely and loathe it at the same time.” That is the spirit of this project. Find brave writers, people who can say “I love my people, and my people drive me mad.”

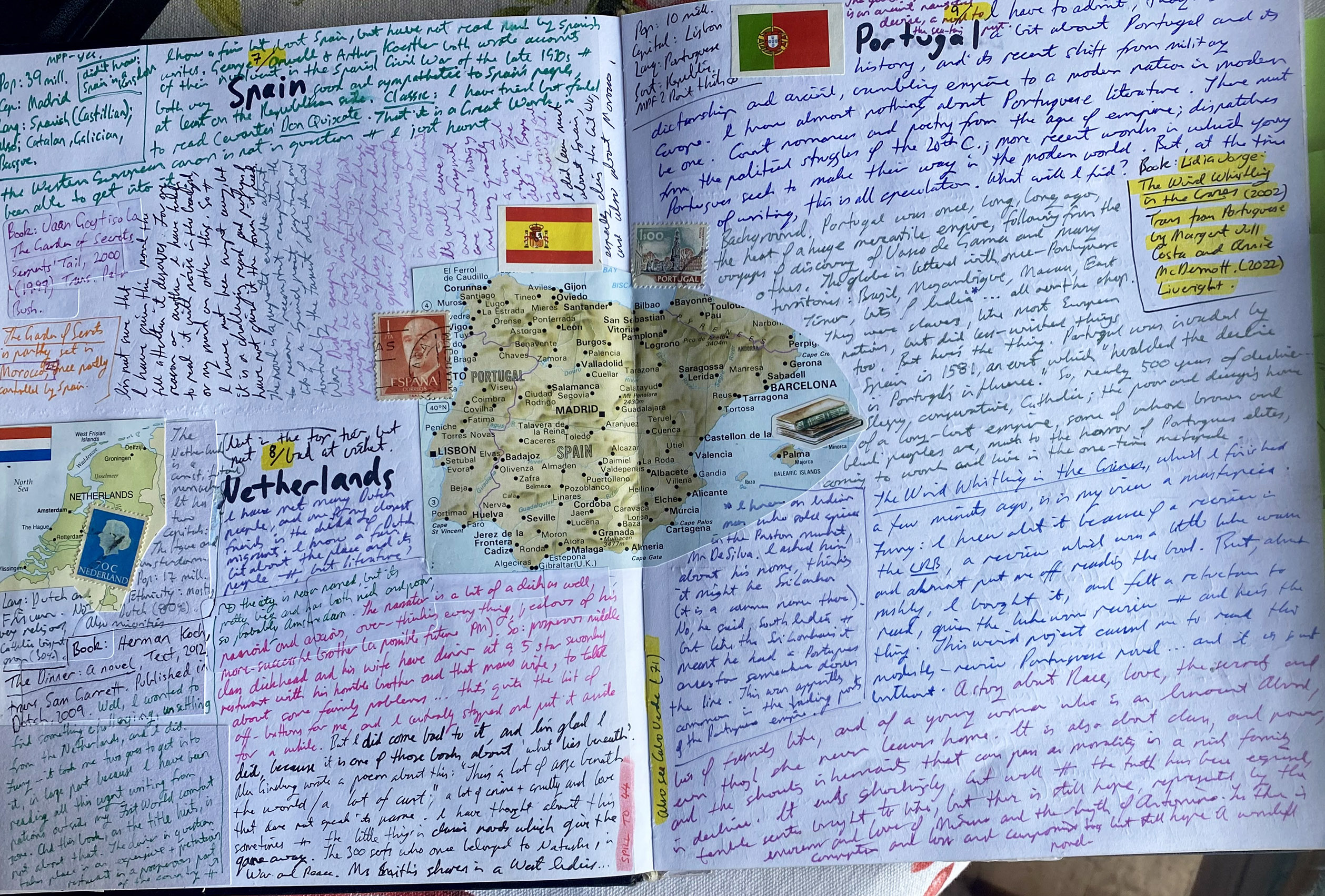

A year later, and the notebook is held together with packing tape. I have found and read and made notes about works from 118 footballing nations. I have discovered so much exciting, passionate, important writing. I have not enjoyed reading so much since I was a teenager let loose with my very own library card. I have learnt so much about the world and its peoples.

People love to share

I have already mentioned that I couldn’t name a single writer from Brazil (ranked #1). For Belgium (#2) I could only think of Hergé, the creator of Tintin. For Argentina (#3): well, I read Jorge Luis Borges at uni, but that’s about it. Spain (#7): I once tried to read Don Quixote, but didn’t get past the windmills. Portugal (#9): see Brazil.

So, I started asking friends and colleagues, people I met at cooking classes or fellow volunteers at a youth mentoring program: anyone I knew who spoke another language or had a background in an unfamiliar culture: “I have started this weird project, can you recommend…”

Between the lines: the reader’s notebook. Richard Evans

I was a little unsure of what reaction I would get, but try it and you’ll find that people’s eyes light up. They are so pleased someone is interested in the culture and literature of their homeland, whether that is Iran (#20), or Malta (#46) or Bangladesh (#192 — good at cricket but rubbish at football). People are full of suggestions and recommendations. You get talking. You quickly learn that they love their country, and their country drives them mad.

Poetry lives

In recent years I’ve only rarely been excited by a new publication from a First World writer. An American poet, Jim Moore, puts it well: “the great majority of contemporary poetry… is frequently smart, cleverly self-referential; but too often essentially empty.” This comes from the introduction to Beyond the Barbed Wire (2016), selected poems by Abdellatif Laabi, a writer from Morocco (#22).

Laabi is a major figure in the nation’s literature. A champion of the independence struggle who later fell foul of the new nation’s rulers, he was imprisoned and tortured and now lives in exile.

I can sing

out of love, for this haunting land

this hijacked country

that electrocutes my memory— From “Letter to My Friends Overseas”

In another poem, “Chronicles from the City of Exile,” Laabi returns to a one-word refrain: “Write.” Again and again. “Write, never stop.” His writing is urgent, passionate, compelled.

There is so much more like this, often in translation and from cultures where poetry is much more popular and mainstream than it is here.

Women are furious

A lot of these passionate writers are female.

Mayra Santos-Febres is a native of Puerto Rico (#170; another American colony-not-a-colony that has its own football team).

A little girl and a father and a dream and a memory broken like a nose at ten years old, with alcoholic breath on top of it all

— From “Broken Strand,” in Urban Oracles: Stories (1997)

There is so much anger.

Like a beggar

I feed my dead

Little girls who die locked away

Trapped in covert factories

Electrocuted doing overt work

Tossed out like garbage or found in sacks

In this country, my country

Those are the words of Victoria Guerrero Peirano in the aptly titled “Urgent Poem.” She is from Peru (#23), and her work appears in the excellent anthology Temporary Archives: Poems By Women of Latin America, edited by Jessica Adcock and Jessica Pujol Duran (2022).

Like so much of the writing by women I have discovered through this project, Guerrero Peirano’s voice is a howl of rage. On every continent, in nations rich and poor, women are furious.

Why does the patriarchy try to silence women, deny them an education? Because given pen and paper, they can express their fury, and tell terrible truths.

Arabic is a major literary language

Abdellatif Laabi is but one of many writers across the Arab-speaking world who deserve much more attention and recognition.

One is Ismail Fahd Ismail, an author of Iraqi origin now based in Kuwait (#149). His novel The Old Woman and the River (2019) is set where he grew up in the Iraqi marshlands south of Basra. There, during the long and bitter war between Iraq and Iran in the 1980s, people living along the banks of the Shatt al-Arab River were displaced. In the novel, an elderly woman defies the authorities to return to her home village so she can bury her husband. She discovers that all the orchards are dying, starved of water. It is a beautiful, elegiac story, in which some love and redemption peek over the terrible parapet of war.

From Iraq itself (#68) comes the writer known as Shalash the Iraqi. In the chaotic years after the fall of Saddam Hussein, Shalash wrote humorous blog posts about life in Thawa City, a would-be-model-suburb of Baghdad. This 1960s housing project, never completed, is a concrete jungle where nothing works — not the power, not the water, not the sewerage. But lots of people live there, and they do their best to get by and somehow feed their children. The American army and various Iraqi militias shoot it out; a motley crew of thieves, charlatans and religious maniacs manipulate their way into positions of power and profit; rubbish and shit pile in the streets. The best of these posts have been collated and translated into a book simply called Shalash the Iraqi (2023). It is a work of satirical genius, up there with The Good Soldier Šchweik.

Graphic novels continue to rise as a literary form

Another work originally in Arabic is Dana Mohammed’s brilliant graphic novel Your Wish is My Command (2023). Mohammed takes the old story of Aladdin’s lamp and moves the action to her homeland, modern Egypt (#39). In the crowded, noisy, smelly city of Cairo, magic is anchored in mundane reality. “Wishes” come in cans, like soft drink, and are variable in quality. When the European Union bans Wishes, the Egyptian government is too incompetent and corrupt to enforce the law. Three interweaved stories tell of ordinary people whose lives get caught up in the black market for Wishes.

It is one of many excellent graphic works this project has brought my way. Another is Valentin Gendrot and Thierry Chavant’s Flic, an expose of the police in France (#4) that started life as a work of investigative journalism but is transformed here into graphic form. It manages to depict the awful behaviour of police — low-level corruption, needless violence, racism — while also probing what underlies these behaviours. I am a criminologist, and Flic is as effective and nuanced a depiction of policing as I have encountered. That it is presented in cartoon form, with all the characters depicted as cats — well, it shouldn’t work, but it does.

We miss out on so much

By ignoring that part of the world that doesn’t write in English and publish in London or New York, we miss out on so much.

I have discovered:

From Argentina (#3), Mariana Enriquez’s Our Share of Night (2022): Magical realism meets Gothic horror meets political thriller, set during the Argentine Dirty War of the 1970s.

From Portugal (#9), Lidia Jorge’s The Wind Whistling in the Cranes (2022): A brilliant, slow-paced story about race, love and the secrets, lies and crimes of family life.

From Brazil (#1), Jorge Amado’s Captains of the Sands (1937): A story set among a group of abandoned and delinquent children in a busy port town in Brazil. Imagine a more honest and sharper-edged version of the adventures of Huckleberry Finn or Oliver Twist that doesn’t dodge the grim realities of life on the margins — with moments of humour and humanity to make things bearable.

From Armenia (#93), Narine Abgaryan’s Three Apples Fell from the Sky (2020): An Armenian novel can’t avoid the Armenian genocide, and this novel doesn’t try to.

“And where are Yasaman’s grandchildren now?”

“They died in the war.”

“And her children?”

“Some died in the famine, others in the war.”

Can a writer be true to the horrors her people experienced, honest about her people’s flaws, and still create an engaging, compelling story in which love and redemption are not lost? Narine Abgaryan shows how.

From Zimbabwe (#125), Tsitsi Dangarembga’s This Mournable Body (2018): Every revolution eats its children, and powerful writing can come from the disillusioned next generation. This novel is a dark, self-aware comedy set in Harare as it steadily falls apart, literally and figuratively, under misrule.

From South Korea (#28), Frances Cha’s If I Had Your Face (2020): A group of young women struggle to get by in the hyper-competitive world of contemporary Korea, suffocated by status and rankings and revolting men. Most horrifying: the pursuit of “beauty” through endless, expensive, risky plastic surgery.

And there are so many more: from Guatemala (#188), Sri Lanka (#207), Rwanda (#137), St Kitts and Nevis (#140)…

Yes, you do get the odd dud. A dull memoir from Fiji (#163); a pretentious and self-absorbed novel from Pakistan (#194); an anthology of poetry from Cameroon (#43) that is more enthusiastic than skilful. But there have been surprisingly few of these, and if I meet one I just stop reading and look for alternatives.

For the most part, I have encountered exciting, inspiring, beautiful writing — fresh, compelling, sometimes troubling — through which I have learned so much about the world and its many peoples.

I could, in theory, have read them anyway. But without this project, or something like it, I would have had no particular reason to read any particular one of them. And there is just so much writing out there: just visit a bookshop or that greedy online enterprise that would be more justly named Piranha. It’s overwhelming. But the books that are easiest to find, and make the bestseller lists, are those produced by a publishing industry rooted in colonial structures and ways of thinking. You need some sort of disruptor, a way of breaking out of the dominant structure.

My disruptor was the FIFA world rankings, but it could be almost anything. A book by every Nobel Laureate, or by every nation competing in the Olympics? A work translated from each of the fifty most commonly spoken languages? Or from the fifty nations ranked poorest in the world by per-capita GDP? Anything that upsets the publishing industry’s apple cart.

As for me, I will persist with my insane quest to decolonise my brain with the World Game. Only ninety football-playing nations to go. •