Australia’s renewable energy revolution offers the biggest opportunity since the gold rushes and the wool and mining booms to revitalise regional Australia.

Not that you’d know it from the claims made by opponents of new projects. A mix of Nimbyism and ideology is portraying renewables as a disaster for the bush. Some of the most prominent antagonists, like shadow treasurer Angus Taylor and the Nationals’ Barnaby Joyce, are attacking from both directions. But they are very coy about their Nimby links, perhaps because voters judge politicians harshly for acting out of self-interest.

The reality is that billions of dollars are flowing into the regions for wind and solar farms. For starters, an increasing number of farmers are finding a way to make a tidy income without having to worry about the increasingly fickle seasons caused by climate change.

Farmers for Climate Action, which has more than 8000 members across Australia, says wind energy companies are offering landholders more than $40,000 per turbine per year, while solar companies are stumping up about $1500 per hectare per year. Although landholders generally hate the large transmission towers being built on their properties, at least they receive compensation of $200,000 per kilometre over twenty or twenty-five years in New South Wales and Victoria.

Many landholders hosting renewable projects are successfully combining farming the sun and the wind with their traditional farming practices, including sheep grazing around solar panels. As well, there is the enormous potential of agrivoltaics — vegetables and other horticulture on solar farms — a practice already widely adopted, and sometimes mandated, overseas.

But the benefits extend way beyond the farming community. The kind of large-scale regional development for which the regions have been crying out for decades provides jobs, contracts for local businesses and improved infrastructure, including roads. According to a projection in a federal government report late last year, an extra 213,000 people will be needed in the clean energy workforce in the next ten years, most of them in the regions.

Then there are the payments to neighbours affected by solar and wind projects, not to mention the community benefit funds that are a standard part of renewables projects, funding affordable housing, community facilities and the activities of largely voluntary sporting, artistic and environmental groups. We’re not talking peanuts — the funds typically pay out an amount indexed to the CPI and are worth as much as $35 million in today’s dollar over the thirty-plus-year lifespan of the projects.

If communities play their cards right, there is no reason they can’t win further benefits, such as contributions to lower electricity costs through solar panels for lower income households.

All this and more is clear from a December 2023 report to the federal government by energy infrastructure commissioner Andrew Dyer. He points out that many communities will be affected by the generation and transmission projects and acknowledges that consultation to date has been inadequate. “However, many communities will also benefit greatly from being part of this massive transition as the associated investment and economic opportunities materialise,” he says.

None of this is mentioned by the small and vocal group opposing renewables. Louise Clegg is a prominent opponent of one of the large proposed solar farms at Gundary, outside Goulburn, southwest of Sydney. At 400 megawatts capacity and with an array of batteries, its proponents say it will produce enough electricity for 133,000 homes. Clegg typically describes herself in the media as a barrister but does not mention she is the wife of Angus Taylor, the former Minister for Emissions Reduction — a title that would be comical if it were not in his case so tragic.

Taylor has a record of opposition to renewables going back to 2013, when as the then Liberal candidate for Hume, the seat he went on to win, he addressed the National Wind Power Fraud Rally hosted in Canberra by Alan Jones. In the same year he spoke of “the absurdity of the economics of wind farms.” In 2019, the then energy minister was the star turn at a $3500-a-head Liberal Party fundraiser hosted by Caltex and attended by leading lights from Woodside and the Australian Pipelines and Gas Association. He went on to become the spearhead for the Morrison government’s so called gas-led recovery.

So there is nothing surprising about his opposition to a large renewables project, though it is ironic, if coincidental, that the developer of the Gundary solar farm, Lightsourcebp, wants to put it close to the Taylors’ property. The real reason for its location on largely cleared grazing land outside Goulburn is its proximity to the high-voltage transmission lines servicing the Sydney market.

Normally, of course, there would be no reason for Clegg to mention her marital status. But voters deserve to know that a senior politician has a vested interest in the position he is taking, all the more so because he represents an electorate that stands to benefit from the development. One of the rare occasions he mentioned Gundary was in 2022 when he framed it in terms of standing up for his constituents. “There is enormous opposition to this project from the surrounding landholders and it is critical their concerns are being appropriately considered and listened to,” he said, adding that he shared their deep concerns.

The Taylors and fellow landholders have been very effective lobbyists against Gundary. In 2022, they persuaded local state MP Wendy Tuckerman to come out against the solar farm. This year they took their cause to Goulburn Mulwaree Council, which voted 8–1 to oppose the project on grounds that include the mystifying claim that there was a “lack of proven data on its contribution to the energy grid.”

As a “state significant development,” Gundary’s future is ultimately in the hands of the NSW government, which has had a particularly poor record of slow decision-making but is now under pressure to speed up approvals to meet federal and state emissions reduction targets.

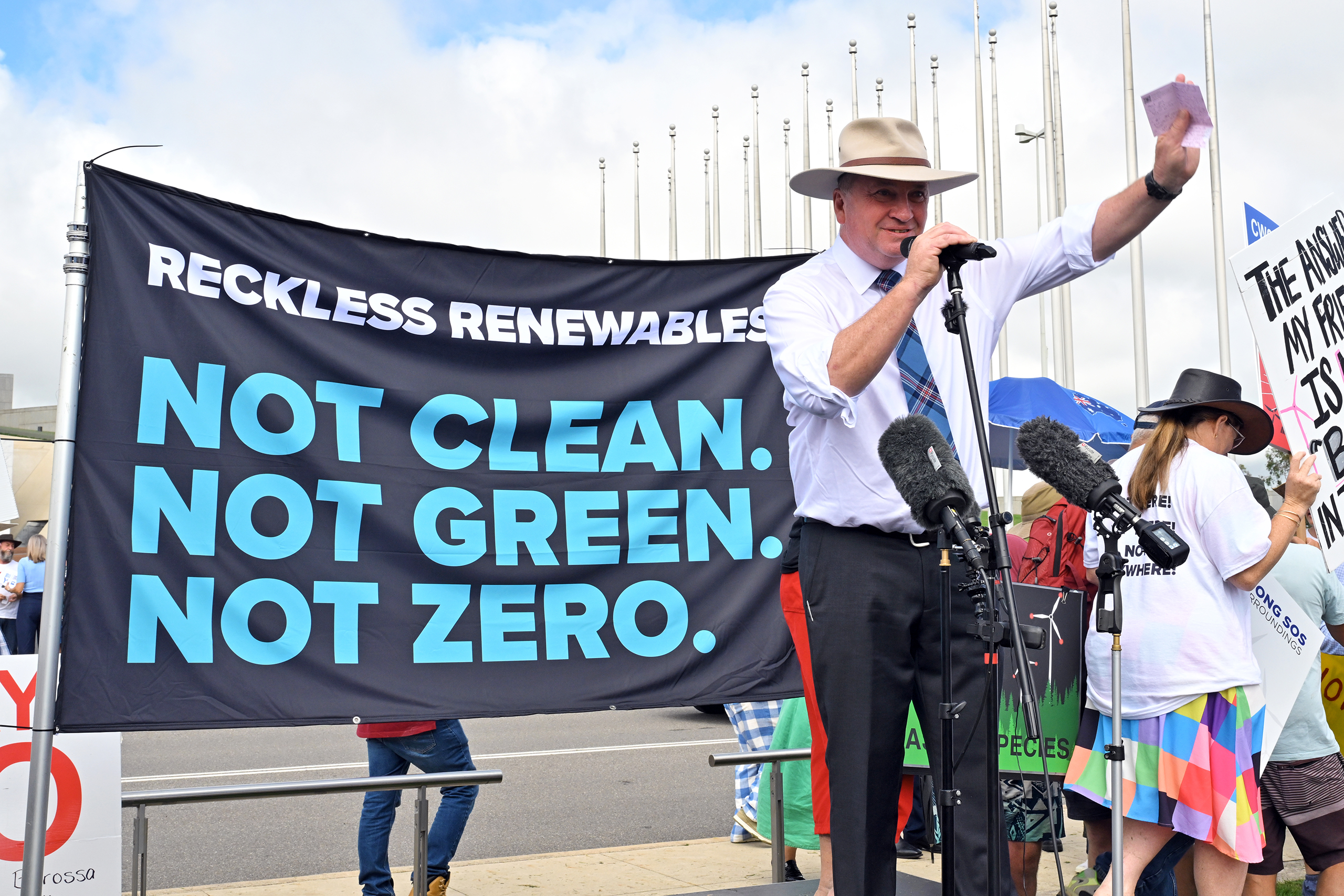

Barnaby Joyce is another politician with a long record of opposing renewable energy. In his typically understated style, he has taken to calling wind farms “swindle factories” and “filth.” He, too, is shy about the Nimby component of his opposition to all things renewable. His farm adjoins a proposed large solar and wind farm in the Tamworth area and there is a separate proposal for a high-voltage transmission line to run through or near his property. Yet he did not mention this in his address to the Reckless Renewables rally in Canberra in February. Nor is it on his Facebook site. Instead he frames his opposition in terms of standing up for the bush.

To repeat, if there is self-interest involved, shouldn’t we know about it? Instead of trying to block developments, Taylor and Joyce should be fighting for benefits for their communities.

In the case of Gundary, if the opponents are successful they will stop Lightsourcebp from spending $540 million in the area. Presumably a large chunk of the money would go towards solar panels, probably imported from China. But there would be plenty of millions left from which the community could benefit. The latest guidelines from the NSW planning department suggest community benefit payments should be paid at the rate of $850 per megawatt per annum indexed for the life of the project. In the case of Gundary, that would mean $340,000 a year for the local community, adding up to about $13.6 million in today’s dollars over the estimated forty-year life of the project.

The company is promising about 250 full-time jobs during the eighteen-month to two-year construction period and numerous contracts for businesses. How many local people and businesses are employed depends on how effective the pressure the community applies and the support they receive from the NSW government.

There is every reason for the affected landholders, despite their opposition, to receive generous compensation for the impact on them of the development. They should be insisting on it and so should the NSW government. Existing renewable developments offer plenty of precedents.

Blocking this project and another of similar proposed size nearby means other sites would need to be found. That would require even more of the high-voltage transmission lines that are arousing so much opposition from landholders. The alternative would be to do what the fossil fuel industries would prefer: keep the creaking coal-fired power plants going at huge cost to taxpayers and fire up the gas-led recovery while we wait fifteen to twenty years for the Coalition’s preferred nuclear plants to be built at eye-watering costs, including for electricity consumers.

Some particularly extravagant claims are being made by opponents about the land area needed for renewables. NSW agriculture commissioner Daryl Quinlivan estimates that wind and solar will require 54,500 hectares in the state by the middle of the century, representing 0.1 per cent of rural land and possibly up to 0.5 per cent for significant agricultural land. Importantly, this land can continue to be used for farming.

The Dyer report also recommends greater involvement by state and territory governments in generating economic opportunities from the energy transition for regional businesses. It suggests identifying and supporting “regions of excellence” in areas such as TAFE training and local manufacturing.

Last year, the NSW government started down this path by promising $128 million over four years for community projects and employment opportunities in the Orana renewable energy zone in the state’s central west. The government says this is a way of bringing forward the benefits to employment and the community before construction of projects begins.

In other words, there are plenty of prospects for regional Australia. Companies are falling over each other to cash in on the renewables revolution. It is up to state governments to accommodate the competing demands of those who don’t want projects in their backyards with the rapid expansion of renewables required if we are serious about climate change.

The question for the third of the population that lives in the regions is whether they take full advantage of the opportunities presented or baulk at the disruption and inconvenience that is an inevitable part of change.

Why look a gift horse in the mouth? •