In June last year one of our best-known international affairs analysts, Sam Roggeveen of the Lowy Institute, floated a striking proposal in the journal Australian Foreign Affairs: a formal military alliance with Indonesia that would vastly extend the ambit of the “echidna” defence strategy he has advanced as an alternative to Canberra’s deeper alignment with the United States.

The idea highlighted a shift in Australian views that has gone largely unnoticed. No longer do strategists in Canberra see Indonesia as a potential enemy. With its population stabilising at around 280 million and no sign that its people are eyeing off Australia’s arid lands — indeed, its government sees the sparsely populated Kalimantan as the place for expansion — Indonesia is now seen as a friendly power worth cultivating. Roggeveen took this shift even further.

The commentary from various specialists in the journal treated his idea sympathetically. Nor, beyond some mention of its military’s human rights record, did they seem fazed by the idea of greater closeness. But they posed the question: what’s in it for Indonesia, beyond the relationship it already has with Australia?

Among the friendly critics was Melissa Conley Tyler, former national director of the Australian Institute of International Affairs, who ran four sessions of a “track-two” dialogue with Indonesian representatives between 2011 and 2018. “My clearest memory is the shift I saw over the decade: a clear sense of Australia becoming less and less relevant to Indonesia,” she commented. “While we were working hard to get Australia’s key sector leaders to see the emerging giant on their doorstep, you could almost see the Indonesians’ attention drifting away.”

A leading Indonesian strategist, Evan Laksmana, said Indonesia was unlikely to see Australia as one of the cornerstones of its foreign policy, ranking it below ASEAN, the United States, China, Japan, Singapore and Malaysia as priorities. For Jakarta, the question was whether it was wise, within its long tradition of formal non-alignment, to lean closer to the West. Australia was seen simply as the West’s local branch office.

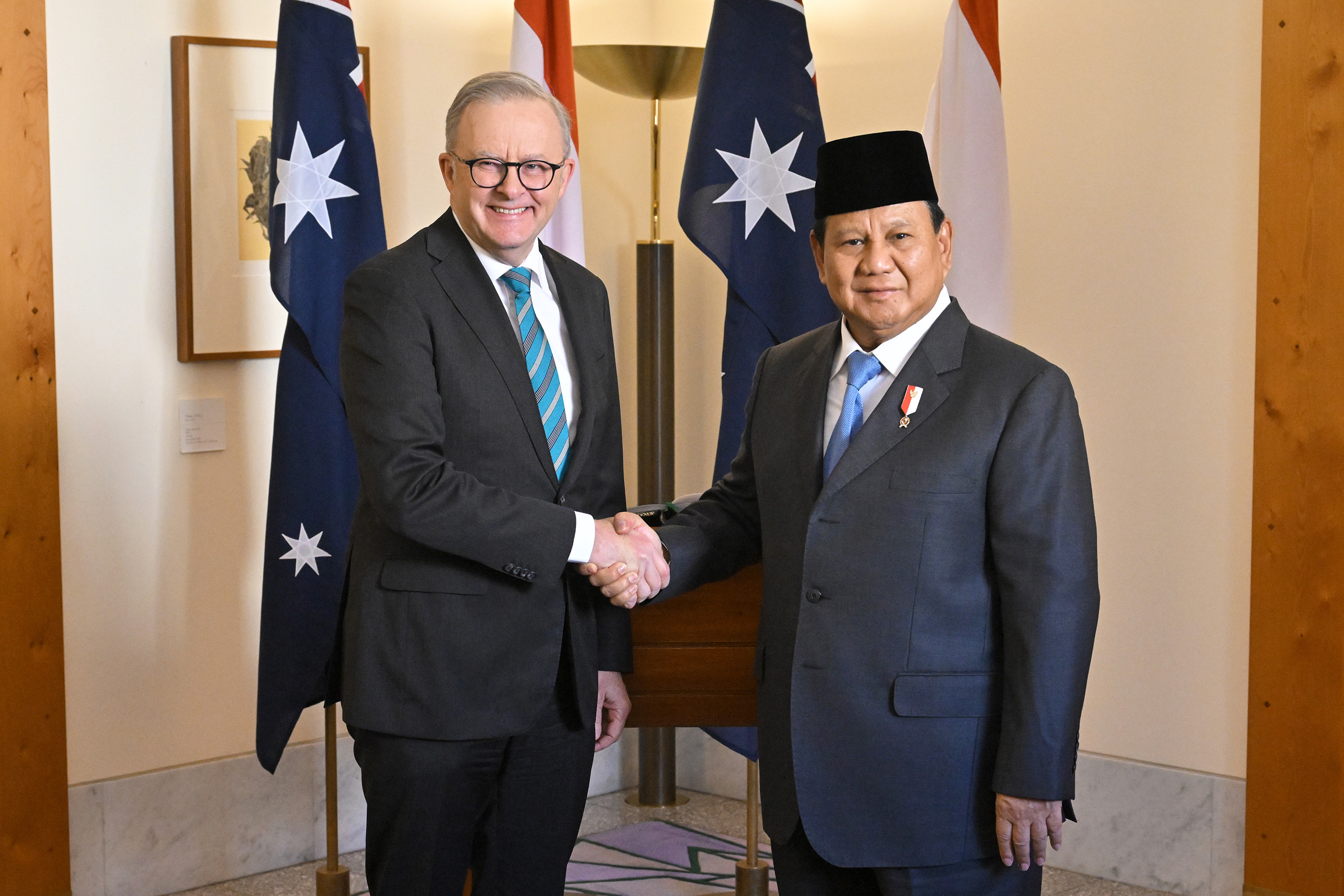

The point that Jakarta now has bigger fish to fry was emphasised last month when Prabowo Subianto, the former army general elected president last year, was guest of honour at India’s annual Republic Day parade in New Delhi. On the sidelines he was negotiating purchase of the Brahmos supersonic cruise missile developed by India and Russia. Earlier in January, Indonesia became a full member of the BRICS association of powers uncomfortable with the America-centred global financial system.

On the other side of the relationship, Conley and others point to a desultory interest in Indonesia among Australians outside the defence forces. The country is Australia’s most popular holiday destination, with 1.37 million visits there in 2023. Beyond holidays in Bali, though, interest doesn’t run very deep.

Trade is well down the list for both countries, at a total of $26.7 billion two-way. Investment is paltry, with only $1.27 billion invested by Australians in Indonesia (and $2.22 billion here by Indonesians). A report commissioned in 2023 by foreign minister Penny Wong from banker Nicholas Moore outlined steps to build up investment in Southeast Asia, but Australian businesses don’t seem to be jumping back into Indonesia, especially as that means to put themselves at the mercy of its corrupt judicial machinery. The recent arrest of Jakarta’s popular former investment board chief Thomas Lembong on a murky corruption charge hardly builds confidence.

In a wider setting, the decline of Indonesian studies in Australia continues. This was emphasised at the end of last year when two big private schools announced they were shutting down Indonesian-language studies. One was Scotch College in Melbourne. The other, much more surprisingly, was the Essington School in Darwin, where Bahasa Indonesia has for many years been a compulsory subject in primary grades and in Years 7 and 8 in senior school.

This is Darwin, a forty-minute flight from Kupang in West Timor and closer to Denpasar than to Sydney. And it’s in the Northern Territory, which has long tried to position itself as Australia’s front door to Southeast Asia.

The federal member for the Darwin region, Labor’s Luke Gosling, an Indonesian-speaker from his army career, says it is a “huge backwards step for government and private schools to be ignoring our huge and strategically important neighbour.” Indonesia was expected to be in the world’s largest five economies by 2040, he said.

“Only half of Darwin and Palmerston schools currently teach Bahasa Indonesia,” Gosling tells me. “In the past, NT governments have prioritised the Indonesia relationship and almost every school taught Bahasa. We also had teacher exchanges between Darwin and eastern Indonesia.” He also sees potential to teach Bahasa in Eastern Arnhem land.

Paul Nyhuis, Essington’s principal, told me the decision was made after long consultations with staff, parents and students, and had aroused little controversy in the school community. None of last year’s Year 8 students had elected to continue with Indonesian. “The student voice had spoken, and the engagement in the recent language has really waned.” The school would now be looking at a more “global” language such as Chinese, French or Spanish for in-school tuition, as well as investigating online language options.

The story is pretty similar elsewhere in Australia. Enrolments in any language at Year 12 dropped from 11.3 per cent of total enrolments in 2010 to 8.2 per cent in 2022. Enrolments in every one of the major languages are down with the exception of Spanish, which is coming up from a low base. Indonesian showed the sharpest fall (47 per cent) from 1161 enrolments to 619. In New South Wales the decline is drastic: from 439 sitting Indonesia in the higher school certificate in 1991 to just seventy-nine last year, despite a small 6.6 per cent bounce in language studies overall in 2024 (which is still only an extra 363 students).

Statistics for study below Year 12 are patchy. Most states have what could be called a token requirement for foreign-language study. In New South Wales, it’s optional at primary schools, and at state secondary schools the only requirement is one hundred hours over one twelve-month period between Years 7 and 10.

“Any teacher that happens to speak a foreign language tends to be designated to teach that language — and that becomes the language policy for that school,” says Sarah Richardson, executive director of Asialink Education at Melbourne University. “It’s almost impossible for a student to start studying a language in primary school and then to continue to study that language into high school, so kids end up with a bit of an introduction to various languages. This feeds into university Asia studies that are also struggling.”

The big exception is Victoria, where in 2011 Ted Baillieu’s Liberal government instituted a policy mandating foreign language study in all schools from foundation year to Year 10. The uptick was immediate. By 2020, 339,124 government primary school students — almost nine in every ten — were learning at least one language. At secondary level, some 43 per cent of all state school students (103,824 of 242,884) were learning a language. Some 181 primary schools and seventy-four secondary schools offer Indonesian.

Why is Indonesian losing popularity? It’s partly evidence of a shrinkage of options at university level. Only twelve universities have an Indonesian studies program, down from twenty-two in 1992. In the 1980s and 1990s, leaders like Bob Hawke and Tim Fischer talked up the importance of Indonesia, recalls David Reeve, a historian and former professor of Indonesian. “At UNSW we were turning students away.”

Then, from 1998, came turmoil and catastrophe in Indonesia: the fall of Suharto, the violent exit from East Timor and resulting Indonesian hostility to Australia, the Bali bombing, explosives at the Australian embassy and a Jakarta hotel, the Aceh tsunami. “Parents didn’t want their kids to study Indonesian because they didn’t want them to go there,” Reeve said. Schools couldn’t get insurance at reasonable cost for study tours and immersions. “Suddenly at uni, the Indonesian department was a charity case,” he said. “We weren’t earning enough to stay open.”

The gap at higher education has partly been filled by the multi-university Australian Consortium for In-Country Indonesian Studies and the New Colombo Plan, which since its start in 2014 under foreign minister Julie Bishop has placed more than 12,700 students and young professionals in Indonesia. Fortunately, Indonesian is a language that can be acquired relatively easily for everyday purposes at that age.

At schools, Reeve views the current curriculum content as a bit boring for young Australians: too much classical Javanese dancing and theatre and not enough contemporary popular culture, in contrast to the anime and Murakami novels in Japanese or Gangnam Style and stylish films in Korean. “Indonesia doesn’t market itself, except as a tourist destination,” he says. And along with Essington’s Nyhuis, Reeve thinks a foreign-language capability hasn’t been pushed as an opportunity-enhancing adjunct to other study majors and professional qualifications, rather than as an uncertain pathway on its own to a job.

What all this means is that an initiative started under the Menzies government in the 1950s to prepare Australians for dealing with the tumultuous new neighbour that had suddenly emerged from the Dutch empire, then was kicked along by the Hawke and Keating governments, is now faltering badly, save in Victoria where a Liberal state government partly stemmed the tide.

“While many in government realise that a lack of Asian-language learning is a major problem, there is a lack of political courage to really address this issue properly,” says Asialink Education’s Richardson. She suggests each state could pick one Asian language for study from Year 1 to Year 12, or require students to learn a language consistently through high school, or mandate language study online moderated by teachers.

For Melissa Conley-Tyler, the fate of language teaching helps explain why Roggeveen’s alliance proposal would fail to attract support. “Defence ties alone — no matter how logical or valuable — cannot create the closeness of relationship required,” she commented. “For Australia to matter deeply to Indonesia, it needs to engage in the whole range of issues that preoccupy Indonesian leaders… the health, education, skills, social infrastructure, digital economy, green energy transition and other challenges Indonesia needs to surmount to escape the middle-income trap.”

Strategic analysts need to broaden their horizons, she said. “Australia’s security requires the use of many tools of statecraft, not just defence. National security advocates can be a powerful constituency for whole-of-nation international engagement, which has flow-on security effects. Australia lacks the political will to do something as simple — yet as game-changing — as making Indonesian language a compulsory school subject.”

And why not Indonesian? It uses the Roman alphabet, is spelled phonetically, has no tones, is accepted at all levels of fluency (kids could try it out in Bali with their parents, then later on while surfing in Nias or seeking spirituality in Java), and offers pathways notably to Hindi/Urdu and Arabic. Nor does country study imply endorsement of the government involved, as ANU China specialist Amy King was recently at pains to point out. If West Papuans do manage to break loose from Jakarta, their common language would be Bahasa Indonesia, not Tok Pisin.

But compulsory? Politicians quick to insist students study more maths, science, English, computer coding or patriotic history have so far baulked at making a choice that would mean facing down the entrenched teacher cohorts of non-selected languages and the ethnic lobbies. Still, this is surely something federal education minister Jason Clare and his Coalition shadow Sarah Henderson should be thinking about. •