Dunera Lives: A Visual History

By Ken Inglis, Seumas Spark and Jay Winter, with Carol Bunyan | Monash University Publishing | $39.95 | 548 pages

During their train journey from the Sydney docks to internment in Hay in 1940, a group of Dunera boys witnessed an incident that would be recounted more than once to the authors of this book. A soldier guarding the internees handed his rifle to one of them and asked him to mind it while he rolled himself a smoke. It was just a fleeting moment on the voyage from Britain to rural New South Wales, but the contrast with the abuses meted out to these “enemy aliens” by callous British sailors and their imperious officers aboard the Dunera could hardly have been greater.

The story serves to confirm the myth of Australia as an egalitarian, knockabout sort of place, a haven from the murderous, bureaucratic brutality of fascist Europe and the indignities inflicted by the British. But it’s also a reminder of the vagaries of memory. In some versions the guard goes on to teach the internees how to roll their own cigarettes; in others he isn’t having a smoke at all but is off to the toilet. According to the version recounted by the writer Walter Kaufmann at a 1990 reunion of the Dunera boys in Hay, the guard explicitly recognises the injustice of their treatment:

“Jesus,” says the digger, “I thought you were enemies, but you’re friends. Jews! Jesus Christ!”

This anecdote is among the many examples of the mythologisation of the Dunera boys, a process Ken Inglis, Seumas Spark and Jay Winter deal with deftly in Dunera Lives. The three historians don’t set out to tear down the myth as much as to gently dismantle it, replacing it with something far richer and even more extraordinary.

The “boys” were enemy aliens transported from Britain to Australia on board the HMT Dunera, a passenger ship used by the British military during the war. They were variously detained in camps at Tatura in Victoria’s Goulburn Valley, at Hay in the flat Riverina of western New South Wales and, later, at Orange on the central tablelands. Most were men rather than boys, the youngest aged sixteen, the oldest sixty-six. Dunera Lives also encompasses another 266 internees brought to Australia from Singapore on the Queen Mary, women and children among them. Helmut Neustädter, who went on to become the famous fashion photographer Helmut Newton, was aboard that vessel, as was sculptor Karl Duldig, his wife Slawa and their daughter Eva.

Karl Loewenstein and his son Fritz in the North Sea, 1927. Courtesy Monica Lee Lowen and Jocelyn Lowen

The Dunera boys are generally remembered as Jewish refugees, but this is an oversimplification. Four out of five were of Jewish background, but only a minority practised Jewish rites and customs. The Nazis had persecuted some of them simply because they had a single Jewish grandparent. The authors see them, rather, as a group of “modern Europeans” of German, Austrian, Czech or Polish origin, mostly “city dwellers” and “often bourgeois,” who “enjoyed the fruits of the Enlightenment.”

Nor were they technically refugees, as is sometimes assumed. Many of them had been living freely in Britain prior to September 1939, some having arrived there as children thanks to the Kindertransport organised by the Movement for the Care of Children from Germany after Kristallnacht in November 1938. With the outbreak of war, they were under suspicion as potential fifth columnists who might secretly assist a German invasion. Prime minister Winston Churchill declared them enemy aliens and swiftly had them shipped off to Canada and Australia.

Dunera Lives, the first of two volumes, is essentially a history told through images; the second volume will include narrative accounts of individual Dunera lives. Together, they constitute the final collaborative project of the highly regarded and much-loved historian Ken Inglis, who died late last year. Inglis’s interest in the men was stirred many years ago when he mixed with several of them as a student at the University of Melbourne. In one photograph late in the book we see Inglis with Dunera boy George Nadel and other Queen’s College residents who achieved first-class results in their 1947 examinations; also reproduced is a sketch by another of the former internees, Leonhard Adam, showing students relaxing outside Queen’s College.

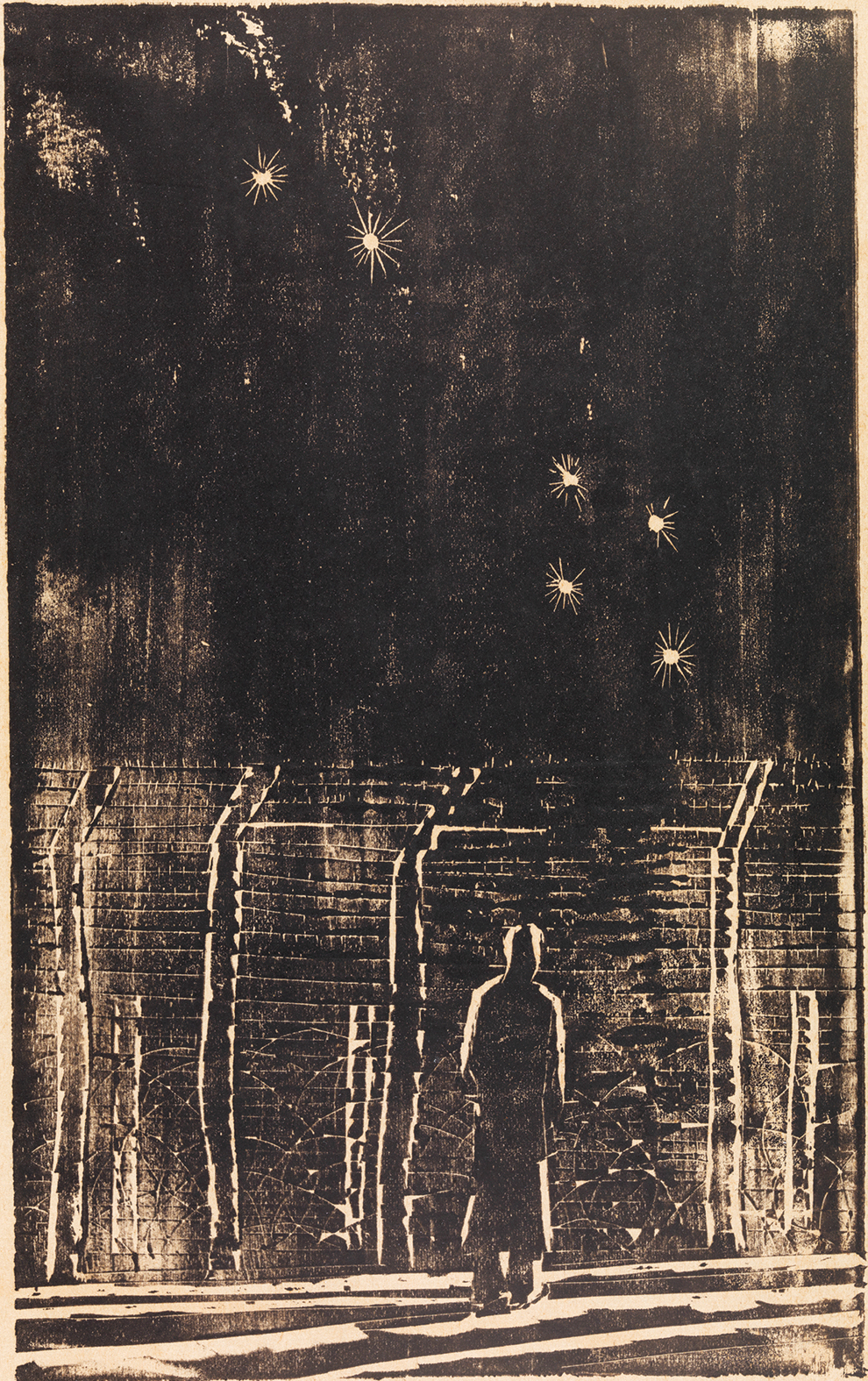

The camp at Orange: Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, Desolation, 1941, woodcut. University of Melbourne Art Collection. Gift of Mrs Olive Hirschfeld 1979. 1979.0179. Copyright: Chris Bell

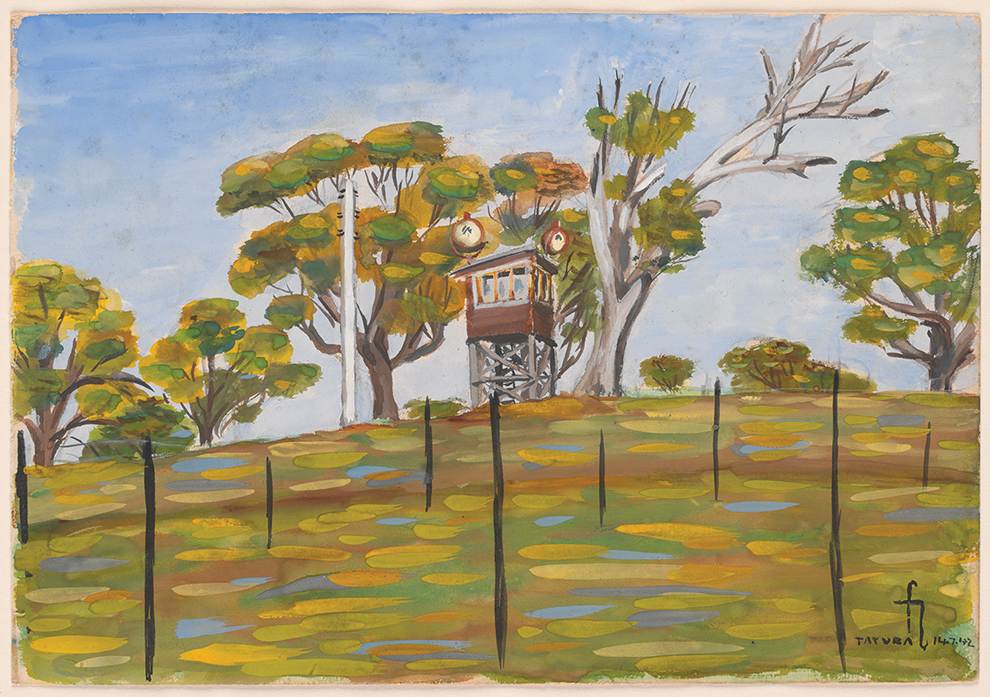

The camp at Tatura: Fred Lowen, Watch Tower with Searchlights, Barbed Wire and Gum Trees, 14 July 1942. Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria, H94.95/29. Copyright: Monica Lee Lowen and Jocelyn Lowen

Several Dunera boys studied or worked at Australian universities after their release from detention, and many became significant academic figures, including philosopher Peter Herbst, economist Fred Gruen, political scientist Henry Mayer, fine arts scholar Franz Philipp, physicist Hans Buchdahl and mathematician turned oceanographer Rainer Radok. Part of the Dunera mythology is that they generally went on to stellar careers as scientists, lawyers, entrepreneurs, industrialists, public servants and artists. As a group, they undoubtedly possessed “substantial education and cultural capital,” as the authors put it, but the story of their postwar lives “is not one of uniform achievement, but of striking variety.”

Fewer than half of them settled in Australia; the rest returned to Britain, emigrated to the United States, helped found the state of Israel or ended up in a variety of other counties. A few dozen returned to Germany, West and East. Both Walter Kaufmann and Heinz Eggebrecht chose to settle in the German Democratic Republic: Eggebrecht rose to senior ranks within the communist regime and died a month after the fall of the Berlin Wall; Kaufmann, one of the youngest Dunera boys, still lives in Germany, where he continued his writing career after reunification. He was back in Australia doing interviews as recently as 2014.

A remarkable number of visual artists, illustrators and photographers figured among the internees, and they left a rich legacy of images. Concise introductions and informative captions put the images in context, but this volume doesn’t so much tell the story of the Dunera boys as show it, in roughly chronological order, beginning with the interwar period in Europe. The affecting photograph (above) of Fritz Loewenstein (later Fred Lowen) holding his father’s hand as they stand ankle-deep in the North Sea on a 1927 holiday speaks to the forthcoming trauma that will wrench Europe apart in a manner that could not be conveyed in words.

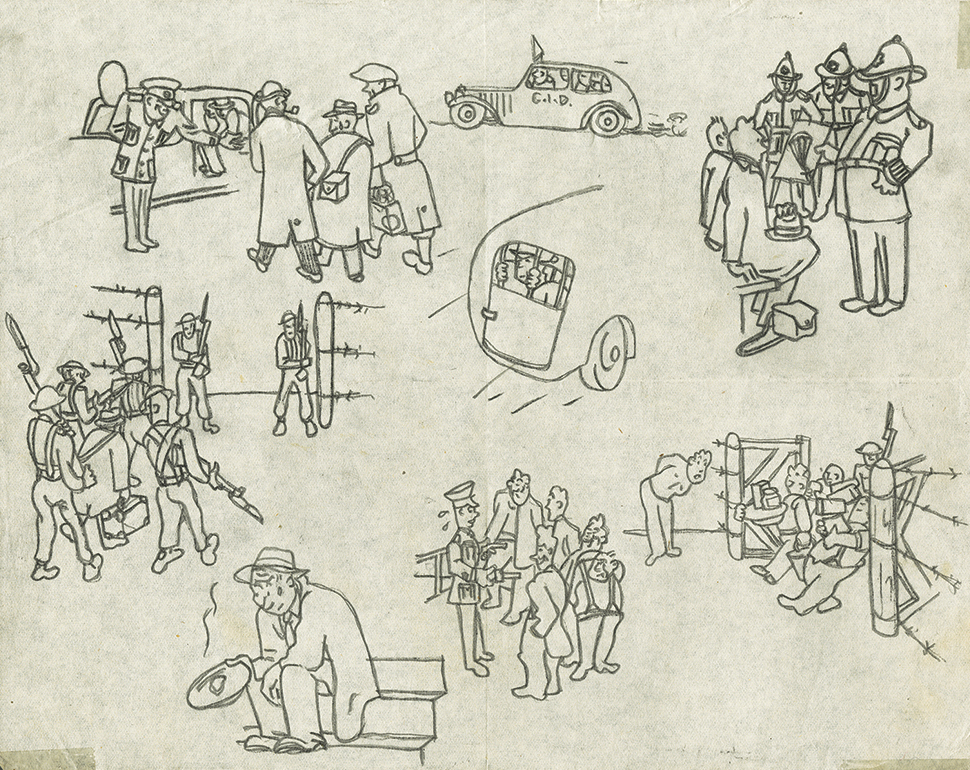

From arrest to internment: Untitled drawing by Fritz Schönbach, c. 1940, pencil on paper. Jewish Museum of Australia collection 3067.15.4. Copyright: Schonbach family

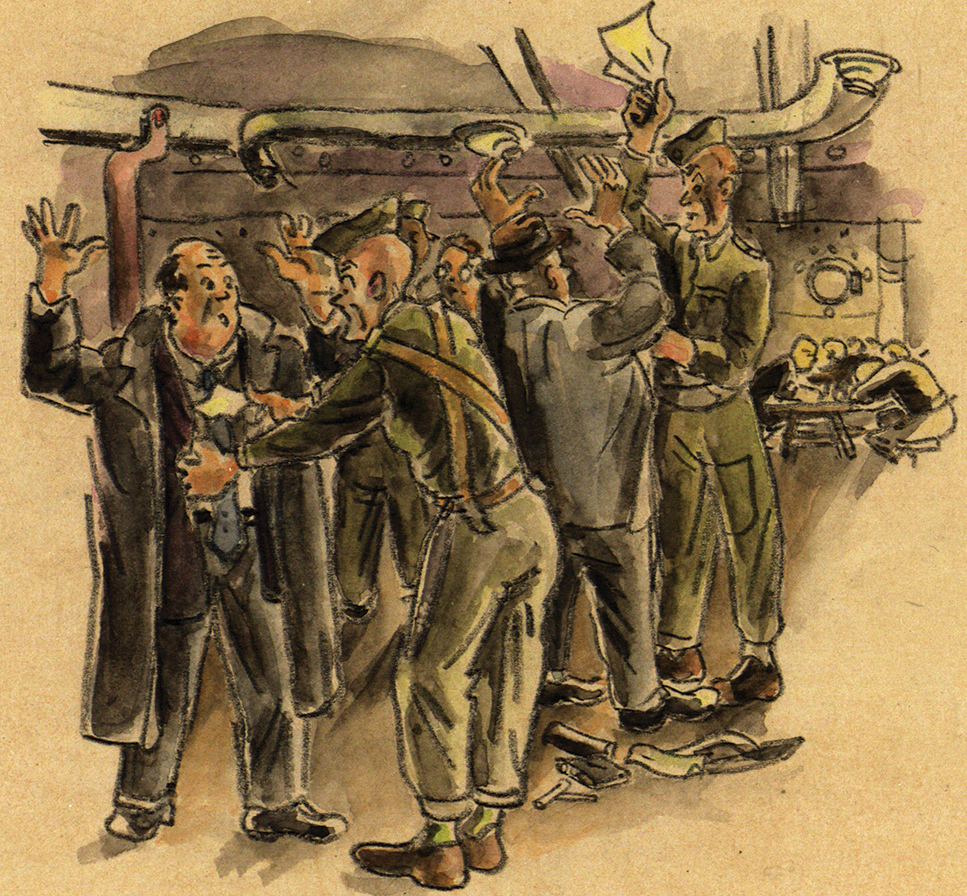

Among the images from wartime Britain are a haunting self-portrait by the artist Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, and a series of compelling cartoon-like sketches by Fritz Schönbach (later Fred Schonbach) depicting the overnight transformation of refugees into enemy aliens. Then come images from the voyage itself, including Schönbach’s sketch of their “reception” by the guards who would destroy, confiscate or steal their possessions, including treasured letters from loved ones, left behind to suffer under the Nazis, whom the boys would never see again.

Fritz Schönbach, Dunera Reception, 10 July 1940, watercolour and pencil on paper. Archive of Australian Judaica, Rare Books and Special Collections, the University of Sydney Library. Copyright: Schonbach family

The ship was terribly overcrowded, and the indignities suffered by the internees included a daily limit of two sheets of toilet paper. Despite the scarcity, a stolen roll of this precious commodity was used by Gerd Buchdahl, Peter Herbst and Peter Lasky to draft a constitution for the boys to manage their own affairs once they were incarcerated on land. Based on the principles of liberal democracy and British parliamentary procedure, it was, to a large degree, implemented in the camp at Hay, which assumed, in the words of internee Klaus Loewald, “the character of a small working republic.” The camp also had its own short–lived currency, printed by the publisher of the local newspaper and praised for its artistry by the manager of the local Commonwealth Bank. Closer inspection revealed that its designer, George Teltscher, who had fought in the Spanish civil war and studied at the Bauhaus, had secreted the words “WE ARE HERE BECAUSE WE ARE HERE BECAUSE WE ARE HERE” into the curls of barbed wire decorating the edge of the banknotes. This soldiers’ lament, sung to the tune of “Auld Lang Syne,” was known to the internees as the Hay–Tatura hymn.

A performance of Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata at Tatura on 8 March 1942. Leonhard Adam, Kreutzer Sonata, 1942, watercolour and ink on paper. Jewish Museum of Australia collection 4024

So it’s not entirely surprising to find that Tatura had its own university — Collegium Taturense — which delivered an average of 113 lectures a week attended by nearly 700 students. Concerts, theatre performances and sports matches were another feature of life in the camps, as the internees did their best not only to fill time and combat boredom but also to retain a sense of dignity and purpose in the face of an indefinite wait for freedom. As the editors of the first edition of the Hay camp newsletter, the Boomerang, put it in February 1941: “Please remember that your mind is not interned, nor is it confined to this camp.”

The injustice of the Dunera boys’ treatment was recognised early. Churchill came to regret the decision to order the indiscriminate detention of those who had sought Britain’s protection. He apologised and instigated a court martial that documented the abuses the boys endured at sea. The Dunera’s senior officer was severely reprimanded and a regimental sergeant major was discharged and jailed for theft. A fund of £35,000 was used to compensate the Dunera boys for their lost and stolen property.

Their treatment in Australia began to change too. By mid 1942 at least 1300 had been set free, hundreds of them returning to England as soon as they could. Some — including the novelist Ulrich Boschwitz — died at sea when the Abosso and the Waroonga were sunk by enemy action. Many of those who stayed joined the 8th Employment Company, a non-combatant battalion of the Australian army, which they sometimes referred to as the 8th Enjoyment Company, a reference to the fact that the numerous musicians and performers in the ranks combined their military duties with theatrical pursuits.

One of the heroes of Dunera Lives is the much-loved commanding officer who made this possible, New Zealander Edward Renata (Tip) Broughton, who even played himself in one of the internees’ colourful productions. Karl Duldig cast a bronze bust of Broughton, and one of the images in this collection is of a handwritten note from Broughton to the soldier-tenor Erich Liffmann. First in Māori, then in English, Broughton expressed, “in thoughts emanating from the depths of my soul,” the belief that Liffmann would one day “ascend to the peak of the mount of song and there dwell for ever.” The enjoyment ceased after Broughton retired, and a number of Dunera boys were court-martialled for minor indiscretions. Michael Levin was punished after he complained about “being treated like a schoolboy, herded about the parade ground by a professional soldier whose only ambition in life seems to be bigger and better wars… and who once actually had the impertinence to call me a ‘queen’ — just because I am in the habit of wearing my hair rather longer than customary.”

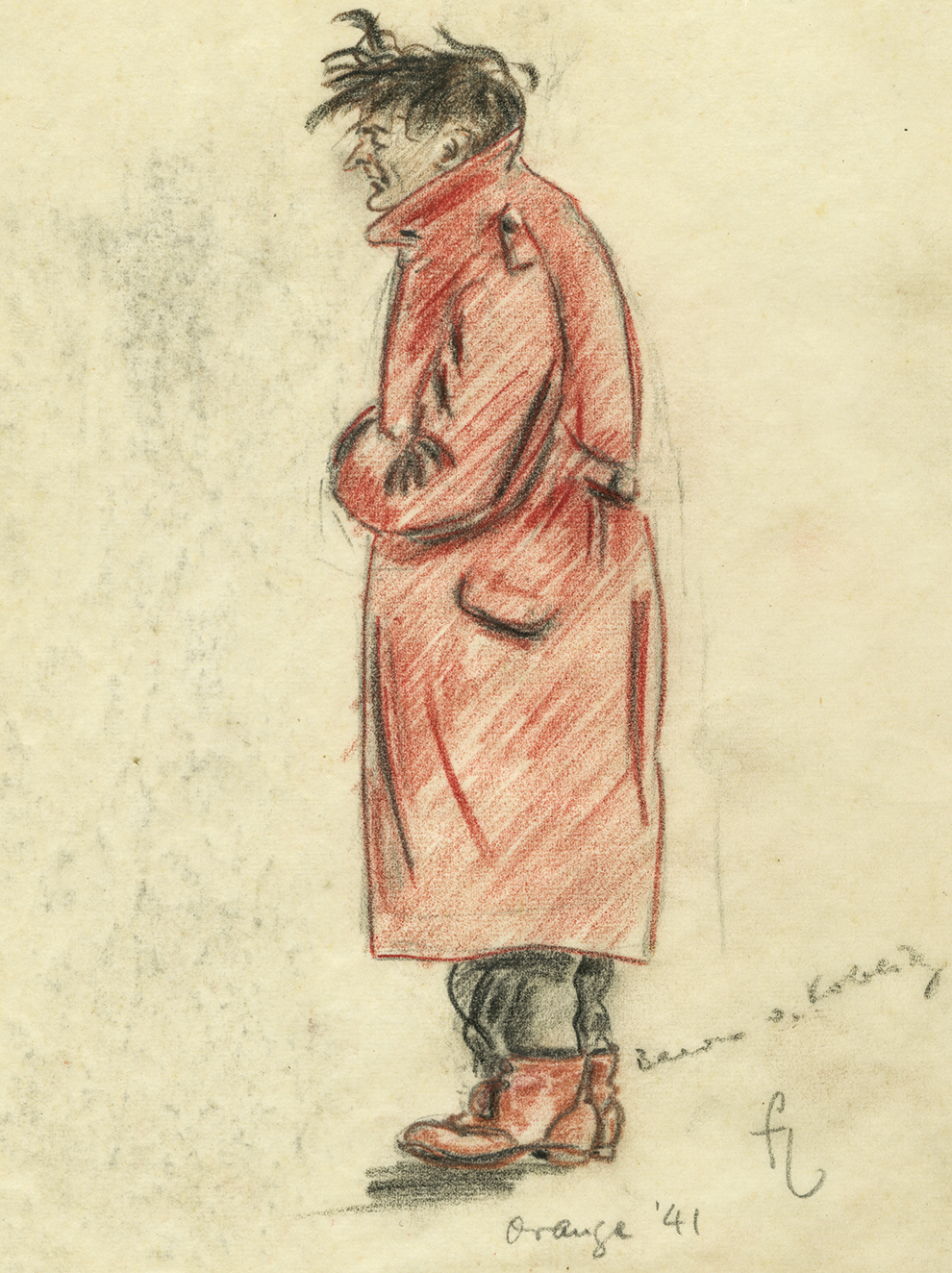

Baron Martin von Koblitz, a Viennese connoisseur of the arts, at Orange. Fred Lowen, Baron von Koblitz, 1941, pencil on paper. Jewish Museum of Australia collection 3419

The main tasks of the 8th Employment Company were unloading cargo from ships in Port Melbourne and transferring goods between trains on the border between Victoria and New South Wales, but a few Dunera boys were called to higher duties. Bruno Lipmann had learnt Japanese before the war and continued to study it while interned, with the aid of a Japanese–English dictionary. He was seconded to the “listening post” in the headquarters of General Douglas MacArthur. There, translating Japanese radio broadcasts into English, this one-time enemy alien became part of sensitive Allied intelligence-gathering.

The authors touch on, but don’t labour, parallels with the treatment of displaced and vulnerable people today, noting that the Dunera boys were persecuted both by the regime that they fled and by countries in which they sought protection. Many moved to Britain before the full extent of Nazi persecution became apparent, not so much in immediate fear of their lives as in the hope of a brighter future. Today they would probably be dismissed as “economic migrants.” As the authors put it, once set in motion “internment and deportation turned into a gratuitous exercise of brutality.” The Dunera boys, like millions forced from their homes today, had “no rights and no nation.” They were not incarcerated for what they had done but because they were wrongly perceived to pose a threat.

The final section of the book shows the boys’ postwar lives — marriages, careers, achievements, disappointments and, as the decades rolled on, reunions and commemorations. A “memory boom” was spurred on by new recording technologies and a few key “memory activists,” and supercharged by books and films, including the 1985 telemovie starring Bob Hoskins. In the process, a diverse group of people, thrown together by fate, were fashioned into one large family. As Inglis, Spark and Winter write, the Dunera Lives constitute a “fictive kinship group” based on “a family of experience rather than of blood lines” and the bonds “these men and women forged and continue to forge in the process of together remembering the past.”

Although the quality of the reproduction is high, not all the images in this volume are visually arresting, nor do all of them unlock a compelling narrative. In determining what to include, the authors’ editorial path has veered towards the compendious. Perhaps a slimmer, more selective volume published on slightly heavier paper stock would have better conveyed the story to a broad readership. But others with a more direct connection to the Dunera generation, or anyone wishing to engage more rigorously with the detail of its history, will have good reason to appreciate the comprehensive approach.

This first volume of visual history is like a series of snapshots, moments rooted in a particular place and time. The second volume promises to complement it with longitudinal narratives of individual lives. Separately and together, they will make a rich contribution to our understanding not only of the Dunera and Australia, but also of the complexities of migration, flight and refuge. ●