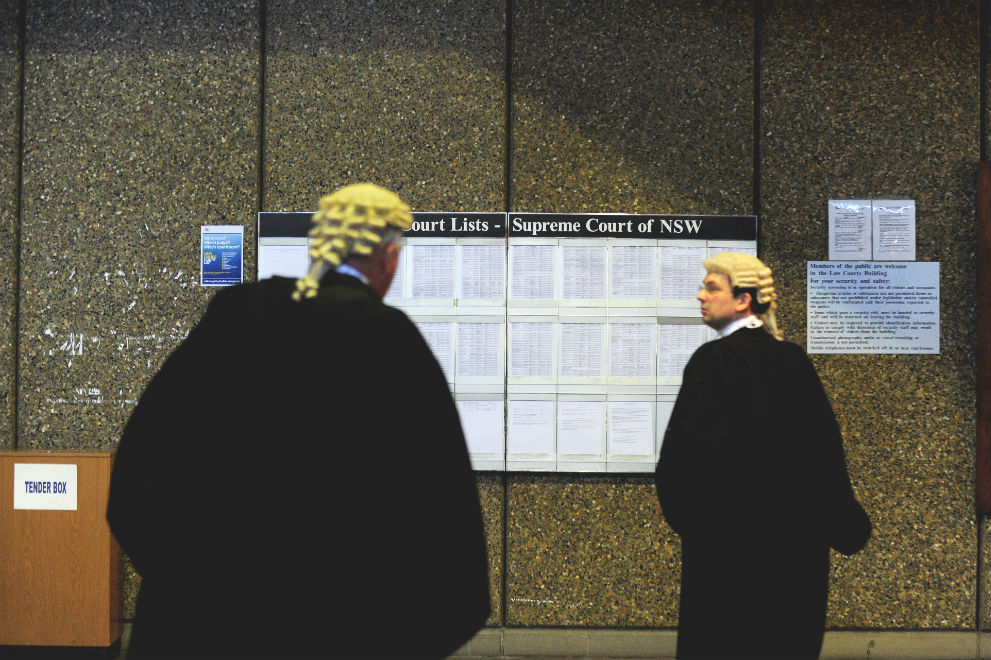

What is it worth to protect a journalist’s source? Helena Liu’s defamation action against the Age has been running for six years now. It is still at the preliminary discovery stage despite what must be enormous costs and stress for the parties involved. On one side are the newspaper and its investigative journalists, Richard Baker, Phillip Dorling and Nick McKenzie. On the other is Liu, a businesswoman who claims to have been defamed by articles published in February 2010. The latest round in the NSW Court of Appeal went her way, with the court lifting a stay on a 2012 order by trial judge Lucy McCallum compelling the journalists to reveal the sources of documents that were the basis of their articles.

The stakes are high for both parties. The articles in question allegedly defamed Liu by quoting from documents purporting to show that she’d made corrupt payments to former defence minister Joel Fitzgibbon. Liu says these documents are forgeries designed to seriously defame her; she wants to know who is behind them so that she can sue them. She also wants that information because it might give her access to the original documents, which she plans to expose as forgeries.

The journalists and the Age claim that the articles deal with an important matter of public interest. Their case for protecting the source of the documents is one of public policy – to protect the free flow of information from whistle-blowers and other confidential sources. At an earlier stage of the proceedings they argued that they should be protected by the implied constitutional guarantee of freedom of political communication revealed in the High Court’s judgement in the Lange case. This argument failed in an earlier round in the Court of Appeal, however, and the High Court refused special leave to appeal on this point.

The defendants also sought to invoke the principle of the “newspaper rule” as a shield against disclosure. According to this principle, media defendants should not generally be required to disclose confidential sources at an interlocutory stage of proceedings. But the newspaper rule is not an absolute immunity, and only applies where a court considers that it serves the interests of justice.

On the facts of this case, the trial judge and the Court of Appeal have found that the interests of justice favour Liu. Liu successfully argued that if she couldn’t find out who passed the documents she would be hampered in pursuing reputational remedies and, ultimately, in proving them forgeries. The Court of Appeal took a somewhat dim view of the defendants’ decision to relinquish a “qualified privilege” defence, in an attempt to forestall the discovery order, only after the Lange defence failed. The court also appears to have accepted, to some degree, Liu’s criticism of the defendants for relying on copies of documents without seeing the originals. It found that Liu should have the opportunity to claim aggravated damages on this ground.

Liu has yet to enforce the order, and it is not clear what will happen next. Subject to any further appeals, the defendants are faced with the choice of breaching their ethical duties (by revealing their source), or facing contempt proceedings, including fines or jail.

The Liu case has been running for so long that law has changed around it. In recent years, New South Wales, Victoria and some other jurisdictions have enacted specific statutory privileges for journalists in the form of shield laws. These laws don’t provide absolute immunity, but they do provide greater protection than the “newspaper rule” by creating a statutory presumption of source protection. Unfortunately for the defendants in the Liu case, this new shield law came too late.

But the new Victorian shield laws were invoked in a recent interlocutory decision (also involving the Age and journalist Nick McKenzie), Madafferi v the Age. In this case, the defence successfully argued that to identify McKenzie’s source for a story about the plaintiff’s alleged mafia link would jeopardise that person’s physical safety. The court also accepted arguments about the strong public interest in publishing such a story, and the chilling effect on such stories if the order were granted. The court found that the plaintiff would not be unfairly prejudiced in pursuing his action over the story if the source were not revealed.

The Age hailed the decision in the Madafferi case as an important victory for journalism. From an investigative journalist’s perspective, though, the shield laws are still far from satisfactory. They are not uniform across Australia – some states protect bloggers and citizen journalists, others only cover people engaged in the “profession or occupation” of journalism. And a court can still exercise a broad discretion to compel a journalist to reveal a source, depending on the facts of the case.

It’s unclear, for example, whether the new shield laws would have changed the result in the Liu case. In contrast to the Madafferi case, the trial judge in Liu was not convinced that the sources would suffer any adverse consequences, other than defamation action, if their identity were disclosed. In the Liu case also, the identity of the sources was found to be critical to the plaintiff’s case, which was not the view of the court in Madafferi. One final factor weighing against the defendants in the Liu case was that one of their articles included some notes accompanying the documents which, it transpired, the source had requested not be published.

In other words, the broad discretion retained by courts under the new shield laws means that the use of confidential sources remains risky. Journalists and their publishers can still face potentially expensive and gruelling interlocutory proceedings and appeals, and ultimately the risk of contempt of court, should their sources be challenged.

Nor has much improved for litigants under Australia’s Dickensian defamation system. In the Liu case, it was two years after publication before the trial judge made the initial order for discovery. Several more years have passed while the parties have fought over its enforcement. The trial judge and Court of Appeal both remarked on the stress that Helen Liu must have suffered pursuing this order. For his part, Nick McKenzie, veteran of both the Liu and Madafferi cases, recently told the ABC’s Media Watch that fighting to protect sources “absorbs a huge amount of time” and “can be very stressful...” The expense of such proceedings is also debilitating. In Britain, it has been recently estimated that the cost of a defamation trial is now around £700,000 (A$1.3 million). In Australia, defamation costs have been described as “incredible and crippling.”

As the Liu and Madafferi cases demonstrate, the uncertain scope of journalists’ source protection is one contributing factor to our labyrinthine defamation laws. But the bigger problem is that these laws were developed in very different times. They are now increasingly ill-equipped to moderate between reputation and free speech interests in a world of rapid digital publication. As “traditional” media outlets shrink and small publishers and bloggers proliferate, a root and branch review of defamation laws cannot come soon enough. •