South Africa has only one traditional-looking cathedral. It’s not in any of the major cities, but in Makhanda (Grahamstown) in the Eastern Cape. Therein lies a tale.

Soon after being founded as a military post — a succession of frontier wars were fought nearby — Grahamstown became the nodal point for the 1820 Settlers, probably the largest state-sponsored scheme sending English people to South Africa. Capturing the trade further in the interior, the town throve. A secessionist movement from the Afrikaner-dominated western Cape soon arose: to appease it, a full session of the Cape parliament met in Grahamstown in 1864. But with the coming of the railways, the town found itself artfully placed on a branch line. Meanwhile huge mineral discoveries at Kimberley (diamonds) and then the Witwatersrand (gold) drained energies away to the North. The editor of the Eastern Star loaded his printing press on to a cart and headed for Johannesburg, where the paper still survives today.

Grahamstown did not give up easily. It began to turn the central Anglican church into a cathedral, adding an extra saint to bring it in line with the new imperial order, St Michael and St George. In the tussle with Cape Town, it had managed to secure an eastern High Court. Meanwhile a number of notable schools established themselves there, perhaps the most significant cluster in the country. These were capped in 1904 by Rhodes University — which still trades under its old name (despite the protests of a few years ago). Brand recognition was deemed to be of greater importance. (Rhodes currently leads in the country’s academic output.)

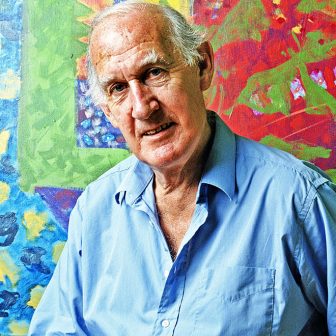

In the late 1960s, a major presence in the town was Professor Guy Butler. Partly to counter Afrikaner nationalism, he turned to Settler history for material for plays and poems, and envisaged a festival in Grahamstown that might be centred on a memorial hall. The Afrikaner Nationalists were prepared to go along with this — at least the English-speaking whites were now identifying with South Africa, rather than with England. (The hated Union Jack was tactfully deconstructed, apartheid-like, into the flags of the whites tribes of Britain.) Even so, one Afrikaner enthusiast promoted the idea of an Anglostan — centred on Grahamstown.

The monument was duly built on a nearby hill, looking like a Crusader fortress. It was stressed that the governing body would promote English-language activities, which deftly left room for changing tack from 18twentology as the need and demand arose. An annual Science Festival furthered outreach.

But the central occasion remains what has become the National Arts Festival, which since 1974 has been drawing performers and audiences from all over South Africa. Gradually it became open to all races; important theatre works have been premiered there. Originally sponsored by the Standard Bank, it boasted that it had become the largest festival on the African continent. Today the emphasis is on dance, physical theatre and stand-up comics; plays are few. There’s jazz, and an enormous range of acts on the Fringe. The Festival is positively bursting with the energies of a truly multicultural South Africa.

But the people are not coming. Walking down the main street of Makhanda on the festival’s opening day, there were no posters up, no printed program to entice people. An improvised restaurant — a regular feature — contained only a handful at lunch. Rhodes University was on vacation; nothing doing there. Some say the festival, organised from Johannesburg now, has lost touch with its roots. Indeed an exhibition of photographs of the Black Sash (a white women’s opposition movement to apartheid), contained scarcely a photograph from Grahamstown itself, one of its bastions. A sports day organised by the town’s two main colleges, I was told, now draws more people than the festival on an average day. It has been on the slide for some time; the Standard Bank downsized its support some years ago.

The deterioration of the town is also a factor. Power blackouts (“load shedding”) are common — but Makhanda has more than its share. One recent twenty-four-hour one was followed by another, shorter one the next day: thieves had taken advantage of the first to steal copper wiring. Tap water is undrinkable — and the general supply so short that during a drought a few years ago an Islamic organisation, The Gift of the Givers, came to the town’s rescue. Livestock wander about the streets; a donkey (offering his services for a Flight to Egypt?) was photographed at the doors of the cathedral. Then there are the potholes; so many that sometimes people have to swerve off the road. Cars need serious repairs; some doctors advise elderly patients to wear neck braces.

Unfortunately it is fanciful to say that the neglect of the old white town has been due to a reallocation of services, to improve facilities in the former African location. Much is to be done there still: there has been sewage in the streets. The main problem seems to have been the Makana council, where the ANC sits entrenched. Twice the state anti-corruption Special Investigating Unit has examined it, and each time has been deluged with so many cases that it has seized up. And so the council just sits there, in what is one of the most solid ANC provinces. Meanwhile people liken it to a mafia, complete with criminal acts. Alas, it’s the local version of a national problem: the respected Business Day recently made the extraordinary claim that South Africa was losing up to US$120 billion every year in corruption.

Yet there are a few positive notes. Quite rarely (given apartheid South Africa) you will see a white mother with Black tot. One of these told me that once an African woman came up to her and said, “Do you think you will love him enough?” (The answer in this case was an emphatic yes.) And what is striking about South Africa now — compared with my last visit a dozen years ago — is that Black and white people go about their daily business in a spirit of acceptance, even mild courtesy. There may be more high walls and electric fences, and a rapid response security service, but it is striking nonetheless that there have been no murders of white people in the town. Tellingly, whereas under apartheid the whites’ dogs would bark at Black people — and the Blacks’ dogs bark at the whites — these days the canines play the field, barking at any pedestrian.

It could be said that the white town has rarely looked better: more houses have been done up, some probably by members of the Black middle class, moving in. Others have been the work of parents with children at school in Makhanda, and — since the Net enables them to work from anywhere — they’ve decided to live closer to the kids. But the parents of some university students from elsewhere in the country have given Makhanda the flick, preferring to send their children to Stellenbosch rather than Rhodes.

The white madam still exists, but in muted form. She may have her “regulars,” Africans who call at a particular time for food or some other handout. And might drive to town, since it is deemed not safe for a woman or an old white man to walk about alone. Fifty years ago the Black youths poking about High Street were often dressed in chaff bags. Now there are car guards, paid in food vouchers, who mind parked vehicles. But not always: a friend returned to his car one day to find it missing — stolen, with the car guard vociferously demanding payment regardless.

Problems can surface at any time. There’s no point in posting anything, since the South African post office barely functions. And there are endless problems owing to shortages. A malfunctioning toilet may stay that way because the necessary parts are in short supply, and have to be shipped. But then changing Australian banknotes can also be a problem. Two banks failed me in a row, because their whole foreign exchange system was “down.” The second bank manager explained apologetically: nowadays “It’s another country!”

The cathedral is still there, of course, and has a mixed congregation. On its walls are many plaques, commemorating deeds of derring-do against the Kaffirs. As this is South Africa’s n- word, the church authorities covered the offending parts of the inscriptions with the soothing words of honeyed Anglicanism. But this was not enough. Strips of matching stone are now plastered over the offending words.

Not far away is St Bartholemew’s, a vigorous building with a superb Victorian pipe organ. It once catered to the (white) artisan class of the town. The morning I went there were four people present, including a Black woman. A man, rather surly-looking, got up and left shortly after. He was not happy that the communion wine and wafers had been pre-consecrated. For the priest was away; so too the organist. Two women stood in to lead the service. The hymns were spoken, not sung. Suddenly there was a click, click, click. An old man on crutches slowly made his way into the church, and up to the communion table. Gnarled, hair thick and streaming, trousers hitched. A poor white looking for a swig? No, a former classics master. The ghost of Grahamstown past.

“We’re stuck!” says a former Rhodes staff member to another retiree who’s just joined us for coffee. “So am I!” he says, as they exchange exhausted smiles. Indeed there’s a new term for those who have left for the Cape, “semigration.” The place is reverting to its prime condition of being a frontier town. Some Brits, with the coming of independence to India, spoke of “staying on”; sometimes the whites in Makhanda seem to be simply hanging on, their lives tautened by daily challenges. •