Best Australian Political Cartoons 2018

Edited by Russ Radcliffe | Scribe | $29.99 | 192 pages

Curiouser & Curiouser: Behind the Lines 2018

Museum of Australian Democracy | Showing at various locations in early 2019, and online

For well over a decade, my old friend Justin has given me Russ Radcliffe’s annual collection of political cartoons as a Christmas present. For even longer, the National Museum of Australia and (more recently) the Museum of Australian Democracy have been running exhibitions of similar scope. These compilation albums of satire and comic commentary allow viewers to review the madness of each year’s politics, generating an accumulated vision of our public life that is often hilarious and seldom flattering. Even politics tragics will need some sort of crib to remember all the prime ministers of our decade, and Matt Golding provides a pointed one:

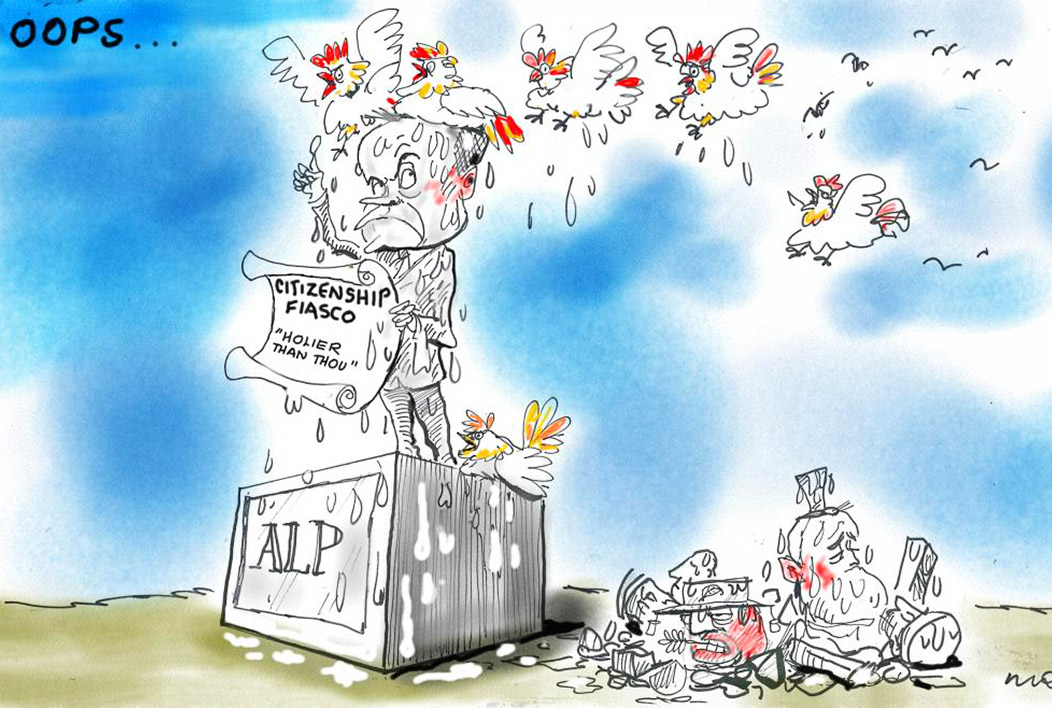

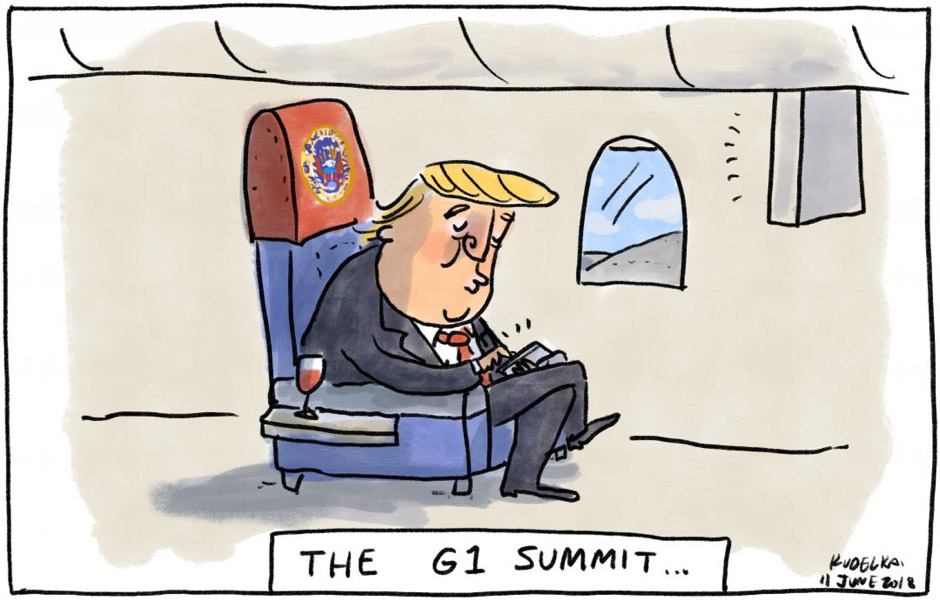

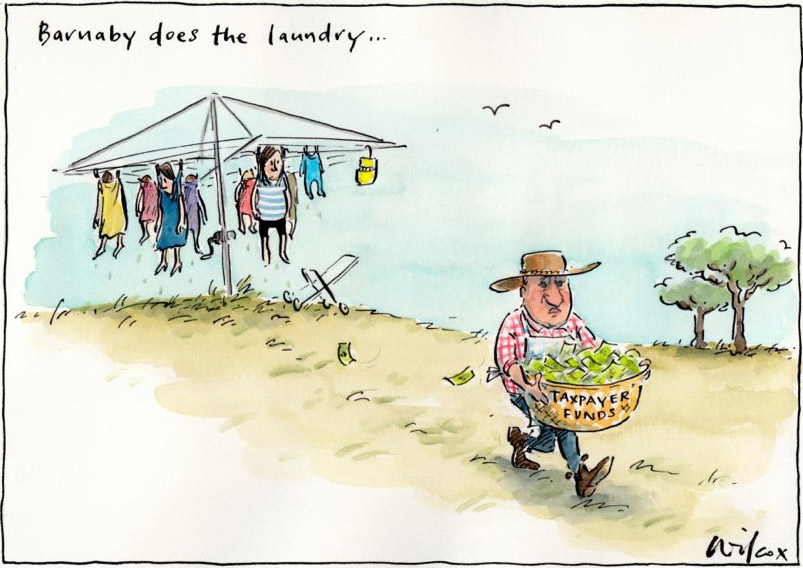

Twenty-eighteen was certainly a bumper year for public idiocy and political self-harm, a bit like Alexander Pope’s 1738, when “Vice with such giant strides comes on amain, / Invention strives to be before in vain; / Feign what I will, and paint it e’er so strong, / Some rising genius sins up to my song.” Would we seriously have believed a satirist who prophesied the mayhem of the High Court’s rulings on parliamentarians’ citizenship? Or the incompetent Brexit negotiations? Or the exposure of posthumous bank charges? Or Barnaby’s love life? Or the Dutton challenge on Turnbull that failed on so many levels except the basic one of removing a PM?

Pope’s conceit was that he had to write satirical exaggeration fast because the rising geniuses of real life were reaching his satirical standards so quickly. A hold-up at the printers could too easily turn something intended as political satire into political history. This must also have seemed true to the cartoonists this year, even before that Magic Pudding of satire, Donald Trump, got counted in.

So make yourself a good strong cup of tea (alcohol may be too dangerously depressive) and wander through Radcliffe’s book or MoAD’s exhibition to relive the lows and lows of 2018. The brilliance of the cartoonists will make the experience a perverse pleasure. Readers will all have their favourites (who has been better than Cathy Wilcox in recent years, I ask rhetorically) and should enjoy them as simply and sadly as possible.

In the lines that remain I want to ring the changes these compilations expose in Australia’s powerful tradition of what used to be known as black-and-white art.

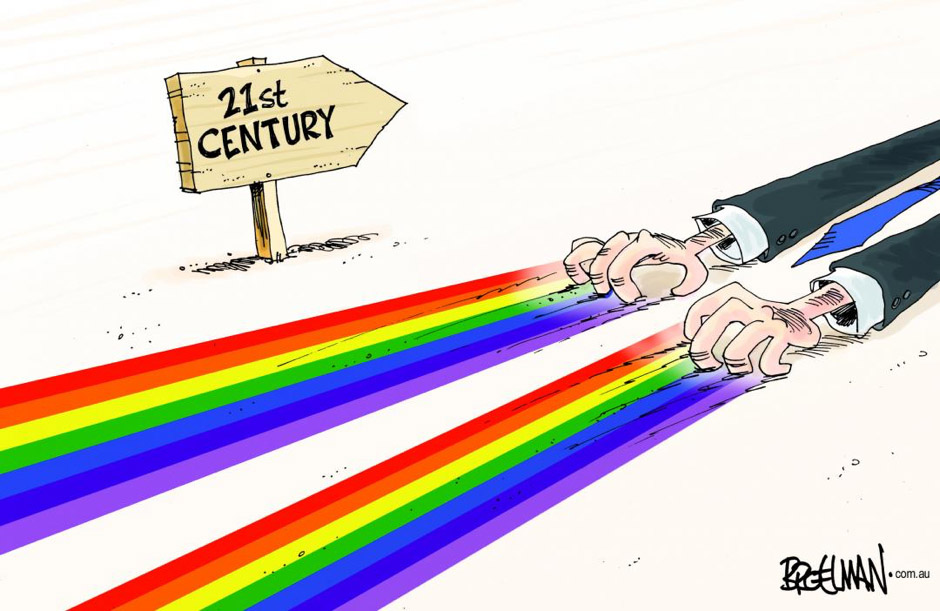

For starters, almost nothing is in black and white anymore; cartoonists are now working naturally and well in colour. For a long time after colour hit newspapers late last century, it was more of a distraction than an improvement, especially given the drab reproduction on newsprint. Warren Brown in the Daily Telegraph was, for mine, the trailblazer, and now colour is integral to the pathos and meaning of many cartoons, like this from Peter Broelman, which reminds viewers so economically of the same-sex marriage debate and the implacable logic of a shift in public morality:

Better colour is, perhaps, the only obvious benefit to cartooning from the rapid retreat from newsprint. In the online versions of the papers, they seem to be hidden away, and are stripped of context if you have the stamina to track them down. Cartoons are just as powerful as ever they were, but they are losing their prominence in an industry that can hardly afford to burn such talent.

And the talent has also undergone a sea change. The cartoons in these two collections include almost nothing by the great generation led by Petty and Spooner (retired), or Tandberg and Leak (deceased), or Leunig (largely departed from topical cartooning). The major voices are Cathy Wilcox, Alan Moir, David Pope, Mark Knight, First Dog on the Moon, Warren Brown, Matt Golding and Jon Kudelka, with David Rowe in his own strange Goyaesque vortex of caricature at the Fin Review.

So we have a new generation of cartoonists speaking more directly to the concerns of a new millennium in its much more fractured mediascape. Curiously, there are no more women than in the 1980s, fewer even in percentage terms than female parliamentarians in the Nationals’ party room. Five out of seventy-five cartoonists on MoAD’s website is a risibly low proportion in the era of #MeToo, and not just a problem for Barnaby Joyce:

So why, despite substantial turnover in the ever-reducing number of regular jobs, are there still so few female cartoonists? That remains a question even if (or especially because) the ideological complexion of the cartooning tribe is such that Peter Dutton can anathematise “crazy lefties” who “draw mean cartoons about me”: “They don’t know how completely dead they are to me.” If you read carefully, the minister is not attacking all cartoonists, who present a somewhat broader spectrum of political views than this suggests. But the point that they are generally of the left is fair enough. Unlike journalism, satire cannot aspire to be balanced, and satirical animus in Australia has tilted left for at least half a century.

Mind you, if the Coalition keeps committing such baroque self-harm as it achieved in 2018, it will be a while before the scales of ridicule have much cause to swing back. Perhaps if you change the government, you change the cartoonists (to mangle Paul Keating). The 2019 collections will almost certainly let us test that hypothesis.

Finally, far and away the most notorious Australian cartoon of 2018, Mark Knight’s internationally incendiary image of Serena Williams at the US Open, appears neither in Radcliffe’s book nor MoAD’s exhibition. I doubt that anyone involved wanted to reheat that debate so soon, and I certainly don’t blame them. But in the long run this will look like a notable omission. The fact that Knight’s controversial image bestrid the world in hours indicates how something fundamental has changed about the place of cartoons in media. No longer do they belong primarily on newsprint in a defined area (a city, state or nation). They can be taken anywhere through social media, and J.K. Rowling in Edinburgh can criticise Knight without becoming much of a Herald Sun reader.

This is real change, and has to be worked around rather than bemoaned. Many cartoonists use Twitter and other platforms to test ideas and images, for example. But it is a significant revision of the rules of the game for satirists, for whom context is a defining feature of what they can say and how it will be received. Add to this the ease of outrage provided by online communication, and it seems to me that twenty-first-century cartoonists will need a thicker skin or a softer pen than their forebears in the age of mass media. When your work can fall into a tiny niche or almost planet-wide notoriety without much warning, making us laugh over our morning coffee is becoming a very risky business. •