Performing King Lear: Gielgud to Russell Beale

By Jonathan Croall | Bloomsbury | $32.99

Variously described as “a mountain of a part” and “the ultimate challenge,” King Lear clearly imposes enormous strains – physical, psychological and emotional – on the actors and directors, perhaps especially the actors, who bring the most daunting of Shakespeare’s tragedies to public performance. As this book makes clear, it becomes even more challenging when director and star are not wholly at one about where the essence of the play and its protagonist lies.

In recent years, Jonathan Croall has staked a convincing claim to being Britain’s leading theatrical commentator and biographer. His superbly researched biographies of Sybil Thorndike (A Star of Life, 2009) and John Gielgud (John Gielgud: Matinee Idol to Movie Star, 2011) set new benchmarks, and he has also written insightful studies of the production processes involved in the staging of such key plays as Hamlet (2001) and Waiting for Godot (2006). In this latest book, he makes a valuable addition to theatre history by mustering an astonishing range of names, from Gielgud, who first played Lear in 1931, to Simon Russell Beale, arguably the greatest stage actor the new century has so far produced, who climbed the highest mountain in 2014.

But the range of the book is not just a matter of researching and/or interviewing the most distinguished actors or directors (and the names of the latter – including Jonathan Miller and Peter Hall – are just as awe-inspiring to those with an interest in theatre). There’s huge variety in what these interpreters of Lear have to say about the play, but the range also reflects the country of production – mainly Britain, but the United States too, and even Japan and Australia – and whether the performance took place in a grand metropolitan theatre or a small provincial one, whether it was elaborately or starkly set, and whether it was located in prehistoric Britain or staged in modern dress in modern times (or at any places or times between).

In talking to so many practitioners of the past forty years, Croall leads the reader to consider how the space in which the play is performed may determine its emotional impact. Does a space like the tiny Southwark Playhouse in London, for instance, lead to a focus on the domestic elements of the play – by exploring the basis of Lear’s attitudes to his daughters, say, or Gloucester’s to his sons? Others, like Corin Redgrave, were more concerned with the political and social implications of Lear’s behaviour and the world in which it operates: what sort of emphasis should be given to the idea of “the houseless poor” as compared with those in powerful positions? Yet others, directors and stars, were determined to bring what they saw as the comedy of the play to audience attention. In other words, there is an endlessly fascinating airing of views about meaning and structure and verse and how these influence the performances put before countless audiences for this most harrowingly moving account of family and kingdom torn about by some of humanity’s less attractive aspirations.

Croall’s own grasp of the play and the history of its staging is what gives coherence to the book and ensures that it never seems like a mere list of notable performances followed by round-ups of critical opinion. He resists the common practice of citing just a few catchy phrases from assorted newspapers, instead skilfully creating a sense of drama about how this or that production was received and encouraging us to reflect further on what may be at the core of the play. On Anthony Hopkins’s Lear under David Hare’s direction, for example, he quotes praise from one critic for the actor’s “magnificent, harrowing animal performance” but acknowledges that others felt Hopkins “had the diaphragm, but not the heart” and “sometimes… missed out on [Lear’s] spiritual side.” This juxtaposing of the commentary often sits provocatively with the accounts by director and star as to how they saw the tragic protagonist.

Speaking of “drama” in this sense of sometimes conflicting views, one of the recurring interests of the book is its wonderfully evocative chronicling of how productions got under way, and how far a famous actor might be able to bring his interpretation to bear on the production if the director had a somewhat different perspective on the play. As Croall’s interviews bear out, this often involved not just flashes of temperament but also highly intelligent discussion between these key personnel. On matters of interpretation, there is quite a lot of talk about how far Lear’s behaviour reflects the onset of dementia. Simon Russell Beale’s Lear, filmed for the National Theatre Live series, was the first time I’d ever seen this possibility foregrounded in a production of the play, but the interviews in the book reveal that it has often been canvassed to help understand Lear’s behaviour. Autocrat as he may be, there is no doubt evidence of a man used to getting his own way but no longer in full control of how he exercises this power.

Some actors undoubtedly brought difficult temperaments to bear on the production process. One such seems to have been Nicol Williamson, an actor of dazzling versatility but one who had, by the time he essayed Lear in 2001, “become notorious for his temperamental outbursts, his falling out with colleagues, and his tendency to miss performances, or even to walk offstage during them,” as his director Terry Hands recalled. Some Lears preferred, as Pete Postlethwaite did, to have mastered their lines before rehearsal began, while others preferred to find their way into the character first; still others, such as Peter Ustinov, had difficulty in remembering their lines during performances. In many cases, actors and directors found recurring problems in rendering the play’s first half, especially in establishing the underlying basis for Lear’s conflict with his daughters and why there is no mention of their mother; or in how to deal with the latter scenes of Lear and the Fool on the storm-lashed heath. Some of the actors felt that Shakespeare’s thoughtless failure to provide Lear with a single soliloquy (try to imagine Hamlet without “To be or not to be”) created a challenge for them in clarifying just what made him tick.

Almost all claimed not to find academic analyses of the play useful: a little dispiriting to some of us who have engaged in this pursuit. I was hoping (in vain) that actor and former academic Oliver Ford Davies might be the exception, but his own very intelligent comments are geared towards how one might go about approaching “such a hard part to play.” Almost all, though, insisted on the play’s contemporary relevance, wherever or whenever the production was set, whether to matters domestic or more broadly social and political. There was also a good deal of stimulating disagreement about how far the play moves towards redemption – and some lively diversity about who is the nastier, Goneril or Regan, and about whether Lear should drag in the dead Cordelia or carry her in his arms or on his back!

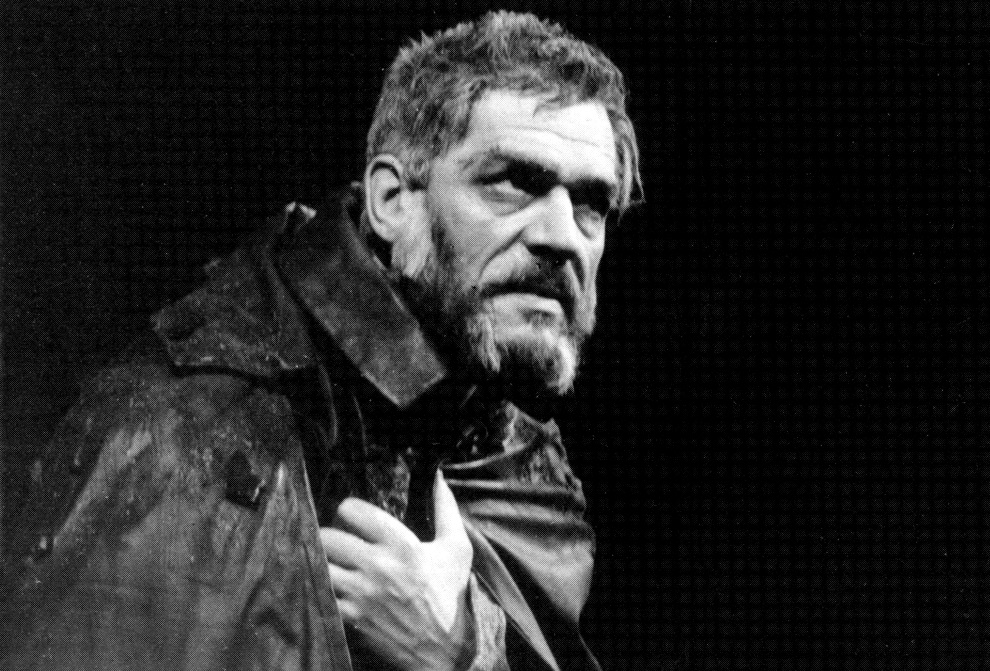

So much in this collection, on matters large and small, is stimulating to read that it seems invidious to single out any passages. If forced to choose, however, I’d be inclined to settle on the wonderful accounts of two near-contemporary Lears at Stratford: Charles Laughton’s for Glen Byam Shaw in 1959 and Paul Scofield’s for Peter Brook in 1962. Laughton was difficult to work with, and his (Australian) Cordelia, Zoe Caldwell, remembered him as “grossly overweight” – which was a handicap because “playing Lear you need an extraordinary amount of energy” – while Ian Holm, playing the Fool, found Laughton “embarrassingly inept.” Croall’s account of the problems of this production makes engrossing reading, and so, in contrasting mode, does Scofield’s approach to Lear as “a wary challenger measuring out an opponent… a strategist rather than a slugger.”

Jonathan Croall should be encouraged – urged – to work his way through the other great roles in the Shakespearean canon. He has a way of drawing out the insights of those practitioners still with us, and of giving life to what may otherwise have been forgotten. If we’ve seen any of the Lears he focuses on, we may feel a new understanding of what we saw; of those we never had the chance to see, we can be grateful for what is put before us about the challenges posed by this mountainous tragedy. •