Senator Fraser Anning could be called the Pauline Hanson’s Pauline Hanson.

The One Nation leader landed in parliament by accident in 1996, having been preselected for the Liberals in Labor’s safest Queensland electorate, Oxley. She was disendorsed after saying out loud what John Howard’s opposition preferred to merely imply — that it was time to stop “special treatment” for Indigenous Australians — but too late to be replaced on the ballot paper. A combination of a huge swing against the Keating government in Queensland, an explosion of publicity for Hanson in the campaign’s dying days, and “Liberal” next to her name on the ballot saw her easily elected.

When Hanson arrived in Canberra and started making more of a name for herself with inflammatory rhetoric about Asians and Aborigines, independent (formerly Labor) MP Graeme Campbell, who also had ambitions to form a national party, complained that he’d been saying this stuff for years — so why was she getting all the attention?

Some people just have it — the luck, the timing and the persona to achieve martyr-stardom — and some don’t.

Fast forward twenty years to the 2016 double dissolution election, and there’s Hanson making a political comeback. To the surprise of most, her One Nation party secured two Queensland Senate spots, one for her and one for Malcolm Roberts. Last year Roberts fell foul of section 44, and next on the ticket was Fraser Anning.

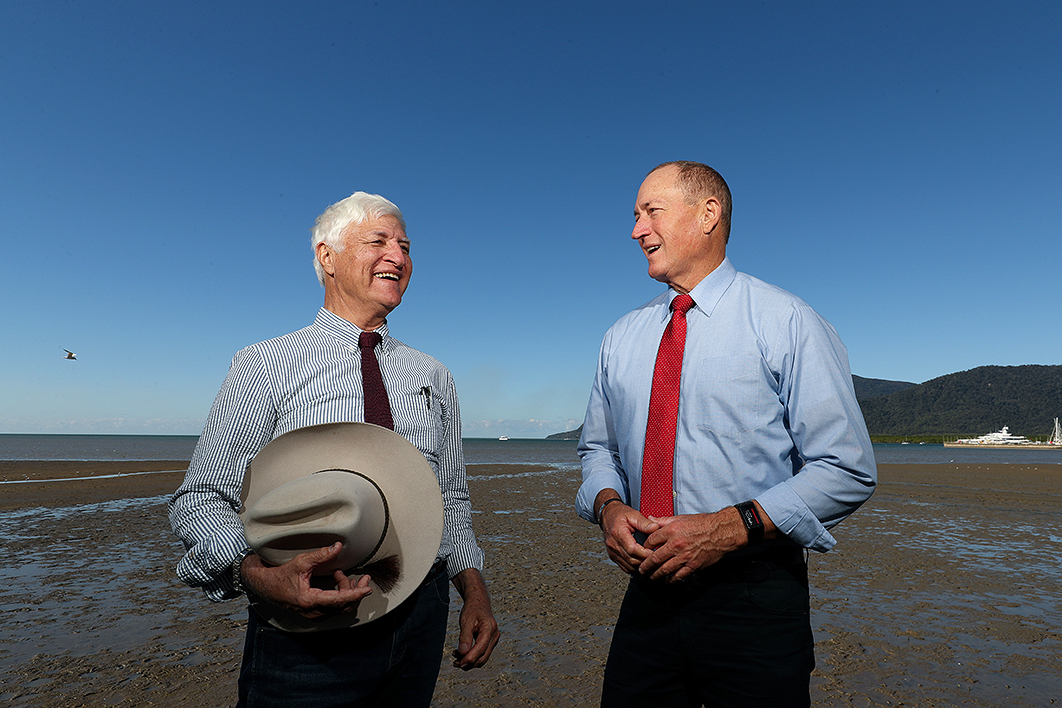

So once again someone who is a political afterthought, who no one thought had a snowflake’s chance of success, is in parliament. Anning soon hopped over to Katter’s Australian Party, and on Tuesday evening he out-Hansoned Hanson in his maiden speech.

Calling himself a “conservative Christian” and “Australian nationalist,” Anning longingly recalled the Bjelke-Petersen era and pronounced all the country’s recent ills as traceable to one Edward Gough Whitlam.

After heaping abuse on Muslim Australians and African Australians (and cheerfully conflating the two), he called for an end to Muslim immigration, a plebiscite on returning to White Australia and, in an evident ploy by either him or his speechwriter to give the establishment a tickle up, employed the phrase “final solution.”

Anning thus joined the cluttered field of politicians trying to be Australia’s Donald Trump, chasing that 10 or so per cent of the electorate. But the others — Tony Abbott, Cory Bernardi, David Leyonhjelm and Hanson herself — fall short of explicitly yearning for White Australia.

Hanson, as Howard did twenty-two years ago, expressed horror at her former fellow party member going beyond the pale.

It is a fine thing that Anning has been roundly condemned in parliament. What’s not so great is the portrayal in some quarters of his speech as emblematic of Australian politics in 2018. Anning is an electoral fluke; unlike Hanson, he will be gone and forgotten this time next year.

And yet it is undeniable that anti-immigrant attitudes are on the rise. There are legitimate arguments for lowering the rate of immigration, but there is no guarantee that doing so would placate such sentiment.

Last week on ABC’s The Drum, the Sydney Morning Herald’s Peter Hartcher described an “elite conspiracy” to operate immigration policy under a “cone of silence” without bringing the wider population into the discussion.

He’s right, but it’s always been like that, or at least since the postwar “populate or perish” immigration push from Ben Chifley’s Labor and then Bob Menzies’s Coalition government. As George Megalogenis wrote several years ago, southern Europeans were far from Australians’ most popular choice for immigrants at the time.

When White Australia was gradually dismantled from the mid 1960s, it was on the quiet, with no recourse to the voters. Because if they’d been asked, they’d surely have said no.

You could categorise immigration as part of a technocratic consensus — along with things like financial deregulation, privatisation, tariff reduction — which is not popular with the electorate, but which the major parties largely agree on. The electors don’t get a say.

Yes, the major parties reserve the right to play politics around the edges: who can forget the 2010 “small Australia” bidding war between the Gillard government and Abbott opposition; after the election it was immigration business as usual.

The electorate generally gets over its disgruntlement at economic prescriptions foisted on it, and concedes that it was all probably for the good. (Not everyone — some no doubt had their lives ruined by the Keating government’s tariff cuts, for example.) But immigration is always a more volatile policy area.

And the last decade has seen a worldwide revolt (at least in developed countries) against that set of prescriptions, a surge in what’s being called “populism.” Voters have stopped eating their greens. It’s no coincidence that since the 2008 global financial crisis per capita income growth has been at its lowest for decades, probably since the 1930s.

The “migrant crisis,” largely flowing from what was seven years ago hailed as the “Arab Spring,” is also a contributing factor, and it too can be cast as having economic roots.

The second world war ended that earlier demagogic decade. What will end this one? •