THE expert panel investigating recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Australian constitution has recommended that the document be purged of all references to “race,” a term it describes as “biologically and scientifically defunct.” Some of the commentary about the committee’s report has mistakenly described one of the key sections under discussion, section 25, as racist. The fact that this is wrong doesn’t mean that the section should stay, but a bit of history (and a trip down the Hawkesbury River) shows what it set out to do and why it failed.

Removing race from the constitution would involve two amendments: to section 25, which seeks to punish any state government that denies the vote to “all persons of any race,” and to section 51(xxvi), which empowers federal parliament to make laws “for the people of any race for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws.” Another “race” provision, section 127 (which excluded Indigenous people from the census count), was excised by referendum in 1967.

Section 51(xxvi) cannot simply be deleted because to do so would take us back to the pre-1967 era, when the federal parliament had power to legislate only for Indigenous Australians who lived in the Northern Territory and the ACT. A debate has already begun as to whether the amended clause should include a general guarantee that laws will not be racially discriminatory.

In relation to section 25, meanwhile, the panel reported that the overwhelming majority of the submissions it received advocated a total repeal. The 1988 Constitutional Commission was of the same view, arguing that the section was “redundant” and that the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 “would prevent the states from discriminating against people on grounds of race.” But that legislation can be amended or even repealed by parliament, which creates a potential conundrum: while the discredited term “race” has no place in the progressive and democratic Australian constitution, would the deletion of section 25 strip the document of what the Constitutional Commission also described as “a mild deterrent to discrimination on racial grounds”?

Before considering a resolution, it is important to look at how the section entered the constitution and what have been its effects. Significantly, its origins were American: when a version of section 25 first appeared in the 1891 draft of the Australian constitution, it came as an amalgam of the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the US constitution. These were post–Civil War “reconstruction” amendments designed to force the defeated Confederacy to enfranchise recently liberated slaves.

The problem was that after federal troops were removed from the south of the United States in the mid 1870s, white supremacists soon rendered the two democratising amendments inoperative. African Americans were effectively denied the franchise by a battery of contrivances including literacy tests, poll taxes, good character tests, grandfather clauses and whites-only primaries. Racially biased state courts and even the US Supreme Court upheld the legality of most of these methods.

The debates at the Australian constitutional conventions of the 1890s showed that the heavy hitters among the delegates were very well informed about the US constitution and its politics. They must therefore have known that the two US amendments were dead letters long before 1891, and were likely to be equally ineffectual in Australia. Why, then, did they bother retaining section 25?

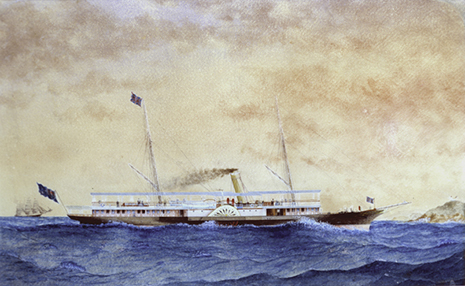

We don’t know for sure. We do have the Hansard record of the 1890s convention debates, but we don’t have the minutes of the all-important drafting committee, nor do we have access to private negotiations such as those conducted on board the Queensland government’s yacht, the SS Lucinda, as it plied the Hawkesbury River, laden with prominent colonial politicians, over the Easter of 1891.

What would become section 25 was the subject of a long, rambling and confused debate at the Melbourne convention in 1898. The radical Dr John Cockburn from South Australia believed the section to be unnecessary because “we are not going to have a civil war here over a racial question.” Some delegates were alarmed that references to citizenship in the fourteenth amendment to the US constitution might confer rights; others feared for the integrity of state Factory Acts, which restricted Chinese involvement in the manufacture of furniture. An exasperated Patrick McMahon Glynn (SA) thought it all unnecessary because “races have been provided for already. Honourable members have races in their heads too much, I think.”

Despite confusion as to its meaning and likely effect, section 25 survived. It reads, in full:

For the purposes of the last section, if by the law of any State all persons of any race are disqualified from voting at elections for the more numerous House of the Parliament of the State, then, in reckoning the number of the people of the State or of the Commonwealth, persons of the race resident in that State shall not be counted.

If used, this section would mean that if a state refused the vote to any group of adults on racial grounds it would have its allocation of House of Representatives electorates reduced correspondingly, depriving it of influence at the federal level. But the section has never been used in this way, despite the fact that Queensland was in breach up until 1965, when it finally extended the vote to all Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Given that federal parliament itself didn’t fully enfranchise Indigenous Australians until 1962, this is hardly surprising.

But what if the federal parliament had wanted to reduce Queensland’s numbers in the House of Representatives at some time between 1901 and 1965? Would section 25 have proved efficacious? No, because it could easily have been circumvented. The killer words are “all persons of any race.” Despite Edmund Barton’s arguing in 1898 that there was no difference between the phrases “the people of any race” and “all persons of any race,” the latter constituted a loophole through which a state could discriminate in extending the right to vote by drafting laws in a manner that did not exclude all members of a targeted racial group. Queensland could have vitiated the potency of section 25 simply by amending its Electoral Act to restrict the vote to forty-five-year-old Aboriginal men, for example.

Circumstances changed in 2007, with the High Court’s decision in Roach v Electoral Commissioner, the challenge to the validity of the Howard government’s 2006 legislation reducing the voting rights of prisoners. As well as restoring the rights of short-term prisoners, the court identified an implied right to vote in the constitution that would make it well nigh impossible for a state (or the Commonwealth) to disenfranchise any class of citizen, including Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. So – the people willing – we can quite safely wave good-bye to section 25. •