TREASURER Wayne Swan has described the 2012 federal budget as a “battler’s budget” and “a Labor budget to its bootstraps,” and commentators have variously seen it as “a big taxing, big spending budget, including a big increase in welfare,” “a big dose of class warfare,” or a bid to “smash the rich.” Indeed, the class war aspects of the budget have been seen as undermining previously announced reforms. But the real story of this budget is less about class war than about a complex interplay of measures in the context of a series of Labor budgets.

While the budget aims to achieve a small surplus – which is no surprise – it brings some unexpected changes, including an increase in Family Tax Benefit Part A, or FTB-A, the income-tested cash payment for families with children, the biggest share of which goes to families with the lowest incomes. All families eligible for FTB-A will receive an increase, but those with two or more children receiving the maximum rate or part of the maximum rate of FTB-A will receive an extra $600 a year, or an extra $300 a year if they have one child. Those receiving the base rate with two or more children will receive an extra $200 a year, or an extra $100 a year if they have one child. The higher amounts will be payable to families with one child earning less than in the range of $61,000 to $67,000 a year (depending on the age of the child), with the income level at which these higher amounts are payable increasing by around $15,000 a year per child. This comes at a cost of around $1.8 billion over four years.

Families with school-aged children who receive FTB-A will also get the SchoolKids Bonus, worth $410 for each primary school–aged child and $820 for each secondary school–aged child. This will replace the Education Tax Rebate, which tended not to benefit low-income families. In 2012–13, this is the largest item of new spending costing, more than $400 million in the coming year and nearly $2.1 billion over four years.

A new Income Support Supplement to be paid to recipients of Newstart (the unemployment benefit) and people receiving Youth Allowance will cost around $1 billion over four years, and give recipients $210 a year for single people and a combined $350 for couples.

The government also announced the first stages of the National Disability Insurance Scheme, substantial improvements in dental healthcare and new spending on aged care reforms, among other items. These initiatives are forecast to cost around $3.2 billion over four years. A further $200 million will go to reforms to childcare assistance for lone parents moving from welfare to work.

These figures need to be put into context. Combined, the “spreading benefits of the boom and support for families” package, the dental health package, the first stage of the disability scheme and the aged care package will increase spending over four years by around $8 billion. Out of a total annual federal budget spending of $376 billion, close to $132 billion or 35 per cent goes to social security and welfare, and a further $61 billion to health. Over that four-year period, $8 billion represents less than 1 per cent of total spending on health, social security and welfare.

At the same time, relatively substantial savings are being made in social security and welfare – including nearly $700 million over four years on Parenting Payment changes, $360 million on lowering the age of eligibility for FTB-A and $127 million in restricting the portability of pensions.

The size of the Australian economy and the size of the federal budget mean that small percentages translate into large numbers. But whether it all adds up to a “big increase in welfare” is debatable.

Some of the smaller changes are particularly welcome, even if their impact is more symbolic than substantial. The Income Support Supplement will be equivalent to an increase of around $4 a week in the single rate of Newstart, which is not likely to make much of an impact on the deepening poverty of this group, but it is at least some recognition of the fact that there has been no real increase – that is, over and above inflation – in the payment for close to twenty years. Just as welcome is the decision to double the liquid assets test thresholds, which will help reduce the likelihood that people will have to impoverish themselves just to get on to Newstart in the first place.

To fund these and other initiatives and bring the budget into surplus the government has outlined around $32.6 billion in savings over four years, although for the purposes of the headline surplus it is the $4.4 billion of savings in 2012–13 that is relevant. In this year the largest single saving is $965 million in defence spending, followed by $600 million by deferring changes to the superannuation concession cap, around $450 million by deferring increases in overseas aid, and $320 million by not proceeding with the company tax cut.

Whether these changes constitute “class warfare” is also debatable. In fact, the one major change that specifically targets the very rich – the reduction in the tax concession for superannuation for very high earners (those earning over $300,000 a year, a subset of the top 1 per cent) – actually has a small cost to revenue in the 2012–13 year. Over a four-year period, the changes labelled as “improving fairness in the tax system” will become more significant, however, bringing in additional revenue of around $2.5 billion.

Assessing the overall effect of the budget on income distribution is complex. Since 2008, Labor budgets have included tax cuts and pension increases, as well as changes to the income-testing and indexation of family payments, and other changes to “middle-class welfare.” Carbon pricing starts from July this year, and a major component of the government’s plans for a clean energy future is an assistance package to compensate for higher prices affecting households. The government will increase pensions, allowances and family payments and cut income taxes for lower-income taxpayers, and the estimated impact of this is likely to be mildly progressive (after factoring in the regressive impact of the price increases).

On the other hand, earlier Labor budgets continued to implement tax cuts foreshadowed by the Coalition government, which significantly raised the threshold for the top tax rate. As a result, relative to John Howard’s last year as prime minister, a taxpayer at $180,000 will have benefited from total annual income tax cuts of around $6000 by 2012–13 while a median taxpayer around $55,000 will have received tax cuts of around $1800 a year. Although the Treasury analysis of the cumulative effect of these tax cuts shows that they are a much higher share of tax paid for lower income individuals, if the tax cuts were calculated as a proportion of disposable income they would appear less progressive.

The Treasury has also calculated the cumulative effect of budget changes since 2007–08 on the real disposable incomes of selected types of households. While this does not measure the overall distributional impact, some of the results for specific types of families are illuminating – although it should be borne in mind that these calculations only show the impact of changes in the tax and benefit systems at the specified income levels. Sole parents completely reliant on benefits have seen a lift in real disposable income of around 7 per cent, and single people have generally done a little better. Wealthier single-income couples with children have generally gained the lowest real increases in disposable incomes.

WHAT is most obvious is that pensioners with no private income have fared best since the Labor government came to office, receiving real increases of 12 per cent for couples and nearly twice that for singles. This massive redistribution to the poor occurred in the 2009–10 budget and was supported by all sides of politics, even if it tends to be largely forgotten now.

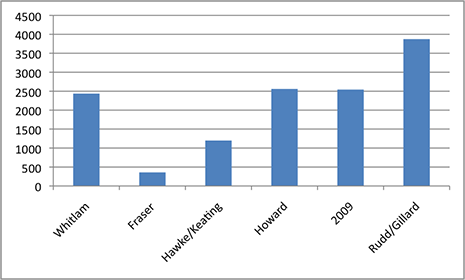

Cumulative increase in real value of single pensions under different governments, 1972 to 2011, in 2011 dollars

In fact, the 2009 pension increase was the largest single increase in real terms for single pensioners since the age pension was introduced one hundred years ago. Overall, the increase roughly equalled all the above-inflation increases that pensioners had enjoyed between 1996 and 2007 under Howard government budgets and was larger than the increases that single pensioners enjoyed in the entire period of the Whitlam government in the 1970s – long thought of as the high-water mark of welfare state expansion in Australia.

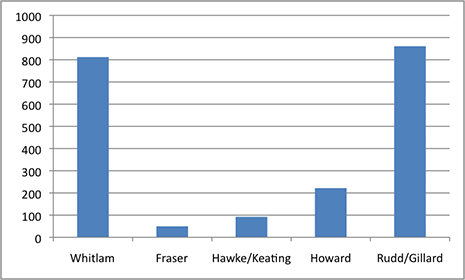

On a year-by-year basis, the comparisons are even more striking. The Whitlam and Rudd–Gillard governments did more for poor pensioners than any other government in the last half-century.

Annual average increase in real value of pensions under different governments, 1972 to 2011, in 2011 dollars

Now that’s what I call redistribution! •