Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World

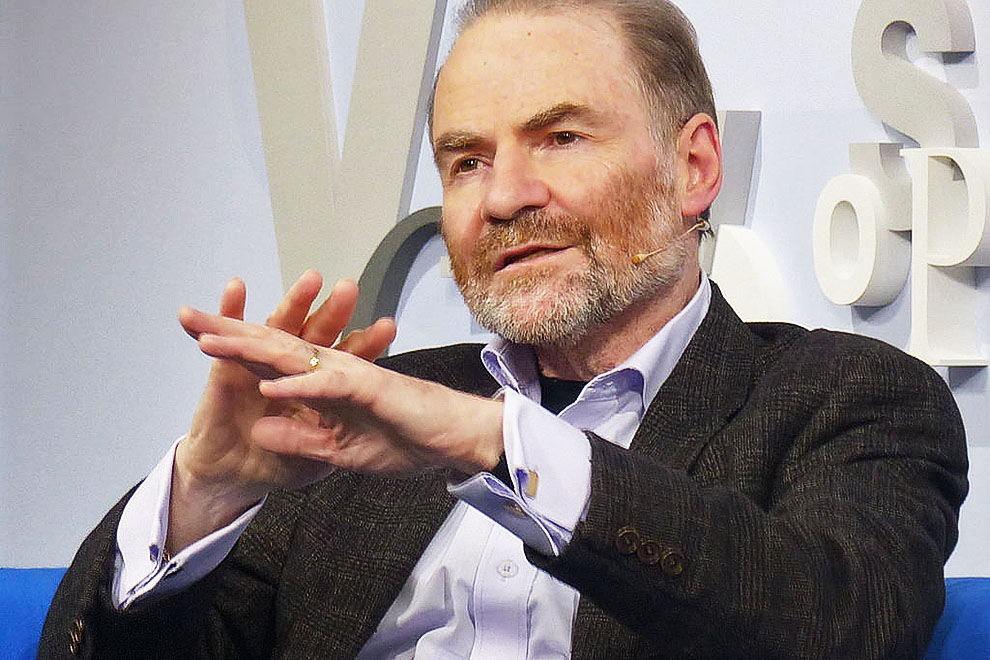

By Timothy Garton Ash | Atlantic | $44.99

Speech, writes Timothy Garton Ash, is “a defining attribute of the human.” Free speech helps people find truth, live with diversity and realise their “full, individual humanity.” It also improves government.

These are the main answers the “Western intellectual tradition” has offered to the question “Why should speech be free?” Garton Ash, a winner of the George Orwell Prize who currently holds positions at Oxford and Stanford universities, comes from that tradition and believes in it. He wants his big, ambitious book, Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World, to be an argument that draws from the Western tradition and starts a conversation with speakers from other places and approaches.

“A more universal universalism” is what he is after. All the people of the world are becoming neighbours, “but nowhere is it written… that we will be good neighbours. That requires a transcultural effort of reason and imagination. Central to this endeavour is free speech.”

Rejecting McLuhan’s “global village” as an inadequate description of, and prescription for, the online world, Garton Ash sees instead a “mixed-up, connected world-as-city” that he calls “cosmopolis.” McLuhan’s was an “extraordinary, seer-like insight” but villages are “small, usually homogeneous and conformist places” where tolerance is not a hallmark. Human beings need more than that.

The ten principles elaborated in the book are Garton Ash’s shot at a set of rules to govern and guide speech in the world-as-city. These “distilled formulations of a modern liberal position on free speech, intended for cosmopolis,” draw on existing templates such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights.

According to his project website, the principles have been “thrashed out in discussions with free speech experts, lawyers, political theorists, theologians, philosophers, activists and journalists from across the world,” and “revised in hours of detailed work with current Oxford graduate students, including native speakers of all the thirteen major languages in which the site’s editorial content appears.” Short, clear principles, comprehensible in all these languages, were the goal.

The principles tweak and supplement familiar elements of free speech. Each gets a one-word shorthand: Lifeblood, Violence, Knowledge, Journalism, Diversity, Religion, Privacy, Secrecy, Icebergs, and Courage. Lifeblood expands to the overarching principle, “Human beings must be free and able to express themselves and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas…” Violence becomes “We neither make threats of violence nor accept violent intimidation…” Knowledge becomes “We allow no taboos…” In turn, “We require uncensored, diverse, trustworthy media…,” “We express ourselves openly and with robust civility about all kinds of human difference…,” “We respect the believer but not necessarily the content of the belief…,” “We must be able to protect our privacy and to counter slurs on our reputations but not prevent scrutiny that is in the public interest…”

The last three principles are more novel. Secrecy, Garton Ash argues, is not always an enemy but it does need to be tested. It “is a condition for the survival of free speech that any limits to free speech… must be open to public challenge.” This is especially significant because international agreements typically allow governments to maintain laws and other measures to protect, for example, “national security,” as well as “public order” and “public morals.” Even “free trade” agreements that otherwise preach openness and liberal exchange of goods and services do this.

The controversial Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement allows parties to apply measures they consider “necessary for… the protection of [their] own essential security interests.” The World Trade Organization’s services agreement does not prevent “the adoption or enforcement… of measures necessary to protect public morals or to maintain public order,” although the public order exception can only be invoked “where a genuine and sufficiently serious threat is posed to one of the fundamental interests of society.”

By Icebergs, Garton Ash means the hardware and software that sit below the waterline of the internet and other contemporary communications tools, the vast and often invisible complex where crucial terms of control, access and preference are set. This is what needs to be defended against “illegitimate encroachments by both public and private powers.”

Courage may be implicit in the acceptance of obligations under existing free speech templates, especially by professional information-gatherers like journalists, but Garton Ash is unusual in elevating it to a principle of its own. “We decide for ourselves and face the consequences,” his tenth principle states. “[T]he truly sovereign state will build its own sovereignty on that of each and every citizen,” he explains, acknowledging that there are countries where people who stand up for free speech “against the armed and booted orthodoxy of their time” will have to “make harder decisions, and face graver consequences, than most of us in the West ever will.”

The second and longest part of the book, where the ten principles are discussed, provides an excellent compendium of many of the free speech flashpoints of recent times: the publication and republication of cartoons depicting the prophet Mohammed as a terrorist; WikiLeaks; the “Right to be Forgotten”; the now central role of social media and search titans like Facebook, Google and Twitter in permitting and censoring words and images. The book’s discussions about offensive and hate speech are directly relevant to state and federal laws about vilification and discrimination in Australia.

To practise the ten principles, Garton Ash prefers relying on “underlying principles or norms” rather than laws: “We should limit free speech as little as possible by law and executive action of governments or corporations but do correspondingly more to develop shared norms and practices that enable us to make best use of this essential freedom.” He gives three reasons. First, in the cosmopolis, the influence of individual law-making entities – countries or corporations – is reduced, though still significant. The engine of the world-as-city, the internet, originated in the United States, and the unique reach and character of American “word power” still means that “what they do inside the United States has an impact far beyond the country’s borders, even when that is not their intention.”

Second, law focuses on extremities, the line that distinguishes prohibited from acceptable (though perhaps repugnant) speech. Individuals, groups and societies ask for more nuanced regulation than this. We “self-regulate our freedom of speech a thousand times a day,” says Garton Ash, according to “countless registers of frankness, politeness, irony, deference, joking and powerplay.” In practice, “religious, social and cultural norms can be more compelling than the letter of the law.”

Third, norms are generally better than laws because they allow speakers to find things out for themselves. “We will never learn how to sail if the state will not allow us to take the boat out. To discover and set limits for ourselves is what responsible adults do.”

Free Speech is a “post-Gutenberg” project, published as a physical book but also as an ebook in which the reader can click through to three deeper levels. These link to secondary sources, primary sources and “further exploration.” The project website also explains the ongoing nature of the conversation Garton Ash and his team are hosting: “We cannot emphasise too strongly that this is just a first attempt at drafting some rules-of-thumb for what we should or should not be free to express, and in what manner we may choose to express it, in a world where everybody is becoming neighbours with everybody else.”

“It is not that there may not be global universal values,” wrote Immanuel Wallerstein, in a passage Garton Ash cites with approval. “It is that we are far from yet knowing what these values are. Global universal values are not given to us; they are created by us. The human enterprise of creating such values is the great moral enterprise of humanity.” •