How to Be a Bad Emperor: An Ancient Guide to Truly Terrible Leaders

By Suetonius | Selected and translated by Josiah Osgood | Princeton University Press | $35.99 | 312 pages

At the same time that an obscure Jewish mystic was preaching the Beatitudes in Galilee (“Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the Earth”), the most powerful man in the known world was living a life of debauchery on his private island just off the coast of Naples.

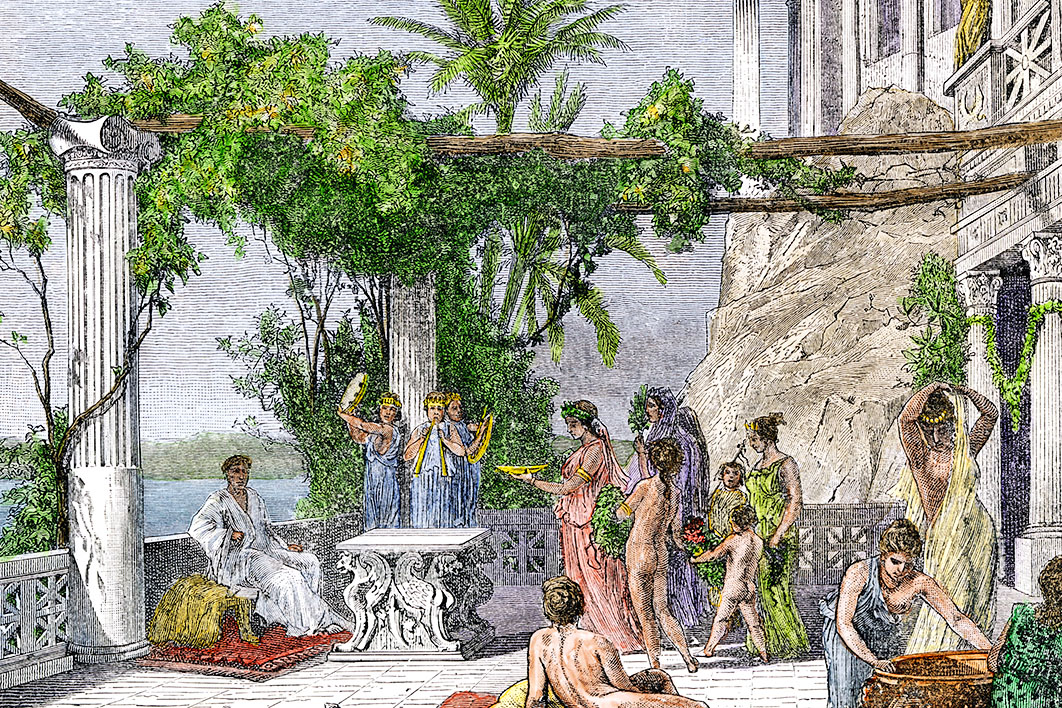

When the Roman Empire crucified Jesus of Nazareth, sometime between 30 AD and 36 AD, Tiberius, the Caesar who ruled that empire, probably felt this momentous event as an elephant feels a gnat’s bite. Anyway, he had other things on his mind. Living in luxury at his five-storey palace, Villa Jovis (“The House of Jupiter”), high on the clifftops of Capri, he had the wealth and power to indulge his every sordid whim — and he didn’t deny himself.

To facilitate all this, he created a minister of pleasures, who, no doubt, supplied the threesomes that the ageing suzerain enjoyed watching, and also organised the teams of teenage sex workers, dressed as satyrs and nymphs, who were scattered throughout the island’s woods and glades and caves, waiting ready and willing to entertain a passing emperor.

We know of Tiberius’s depravities because of The Twelve Caesars, which was written by one of the world’s first biographers, Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus. Indeed, the lurid descriptions have kept his work on bookshelves and reading lists for almost two millennia. How to be a Bad Emperor is a shortened version of this ancient classic, and a deft introduction to the world and mindset of the Caesars.

Suetonius was a lawyer, public servant, and what we might call an independent scholar. He wrote many works, including On Notable Prostitutes and On Cicero’s Republic; but only The Twelve Caesars and parts of On Illustrious Men have survived.

Suetonius’s twelve Caesars can be broken into three groups.

There’s what I call “Big Julie and the Hollywood Caesars,” but proper historians call Julius Caesar and the Julio-Claudian imperial dynasty — Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero.

Then there are the three Civil War Caesars — Galba, Otho and Vitellius — who came and went in a single year, during ancient Rome’s little-known Australian politics phase.

And then there’s the Flavian dynasty, made up of Vespasian, Titus and Domitian. Still crazy, but not as crazy as the Hollywood Caesars, and therefore largely unfilmed.

It’s an impressive cast of characters. And Suetonius knew a lot about them. He was born in 69 AD — the year of the Civil War Caesars — and grew up under the Flavians. He would also have known men who knew the Julio-Claudians from Tiberius onwards. And, as the secretary of correspondence under the Emperor Hadrian, he would have had access to the imperial archives.

The Twelve Caesars doesn’t conform to our modern idea of narrative biography. It’s more like a dossier of intelligence reports. The life of each Caesar is described under a series of headings, including Background, Public Life, Private Life, Personal Characteristics and Death.

Besides his sexual predation, Tiberius also indulged in extravagant violence. He starved two of his grandsons to death and had a centurion gouge out his daughter-in-law’s eye. As one contemporary poet — who understandably wished to remain anonymous — wrote, “He has no taste for any wine, since now he thirsts for blood.”

The other Caesars were just as wanton and cruel. Caligula, for example, famously threatened to make his horse a senator, but his real crimes were much worse. He killed his brother, forced his father-in-law to slit his own throat, and raped his sisters. He sealed up the granaries and inflicted famine on his people. He disfigured nobles he didn’t like with a branding iron. He once declared, “I wish the Roman people had a single neck!”

Suetonius says Caligula admired his own shamelessness above all else. As he once said, “I can do whatever I want to whomever I want.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, Caligula was hacked down by his own bodyguards.

We learn a wealth of nauseating detail about each man, but the cumulative effect of reading these dossiers is even more powerful. All of them feared the knife in the night. Only a couple died of natural causes, the rest committing suicide (under political pressure) or falling to assassins. Tiberius was smothered with a pillow. Claudius was poisoned. Vitellius was overthrown in a coup, dragged from a hiding place — much like Saddam Hussein — and put to death in front of a laughing mob.

But while they lived, they had absolute power. And in death they were divine — or at least they expected to be. As Suetonius records Vespasian saying just before he died, “Dear me, I am becoming a God.”

The Romans had invented a system of government with madness at its heart. As Gore Vidal wrote in an essay about The Twelve Caesars, “In terror of their lives, haunted by dreams and omens, giddy with dominion, it is no wonder that actual insanity was often the Caesarean refuge from a reality so intoxicating.”

And it is this insight that accounts for the book’s continuing popularity and relevance. Since the first human societies formed, the story of how to organise them has involved a tension between two things: democracy and dictatorship. Whether Suetonius intended this lesson or not, The Twelve Caesars warns that, without checks and balances, without limits and restraints, without free speech and fair elections, life can end up being a beautiful island run by a mad king.

Though he didn’t know it at the time, Suetonius was also writing about the forty-fifth president of the United States, Donald J. Trump — or at least that’s the unspoken marketing conceit of How to Be a Bad Emperor.

Josiah Osgood, who teaches classics at Georgetown University, has selected, translated, and written a commentary on the highlights of just four of Suetonius’s power portraits: Julius Caesar, Tiberius, Caligula, and Nero. If you want to learn more, there is always the Penguin Classics edition of The Twelve Caesars, translated by the poet, classicist and author of I, Claudius, Robert Graves.

Though he is never mentioned by name, Trump’s increasingly bizarre and dangerous dumpster fire of a presidency often comes to mind as you read How to Be a Bad Emperor. (Osgood calls the chapter on Tiberius, with a knowing wink and a nod, “Spend All Your Time at Your Resort.”)

Indeed, you can’t read about Julius Caesar’s obsession with his male-pattern baldness and not think of a certain epic comb-over. Nor can you read about the rumours that Nero sang an aria, “The Fall of Troy,” in full stage costume, as Rome burned, without thinking of the tragedy of America’s Covid-19 response.

And when you finish this book, you can’t help but ask, “What will the United States look like if Trump gets a second term?” •