A Town Is Born: The Fitzroy Crossing Story

By Steve Hawke | Magabala Books | $35

STEVE Hawke’s A Town Is Born narrates the evolution of contemporary Fitzroy Crossing, a story common to many remote settlements across northern Australia in the wake of the pastoral era. It’s the scenario that Alexis Wright evokes in her depiction of Pricklebush in Carpentaria, an area created “as a human dumping ground next to the town tip” of Aboriginal people discarded “by the pastoralists, because they refused to pay the blackfella equal wages, even when it came in.” While the “winds of change” ushered the counterculture and civil rights movements into the country’s southern cities during the 1960s, Hawke observes that, in remote Australia, they “blew down an industry, a regime, a culture that for the best part of a century had thrived on a semi-feudal system of co-dependence between the all-powerful station bosses, and large communities of unpaid Aboriginal workers and their families.”

The catalyst was the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission’s decision in 1966 to establish equal wages for Aboriginal labourers in the cattle industry. Shortly after, the 1967 referendum that allowed the Commonwealth to legislate on behalf of Aboriginal people ushered in the recognition of citizenship rights. The same period saw strikes and protests by Aboriginal pastoral workers in response to poor conditions, most famously in Vincent Lingiari’s Wave Hill walk-off, but also, as Hawke recounts, on stations across the Fitzroy Valley in the Kimberley.

Noel Pearson, in Up from the Mission, and others have chronicled the largely northern narrative of social upheaval that followed the pastoral era, and the ensuing culture of Aboriginal unemployment, alcohol and welfare dependency. Hawke’s contribution in A Town Is Born is to tease out the history of relations between the local Aboriginal population and white settlers within the microcosm of Fitzroy Crossing in light of this period of change. Fitzroy Crossing is a small town in the Kimberley with a population of 1500, the majority of whom are Aboriginal; the book also encompasses the outlying Fitzroy Valley, however, which includes thirty-five distinct communities on Aboriginal homelands, many of which were excised from pastoral properties.

Fitzroy Crossing is perhaps best known through mainstream media coverage for its alcohol issues and socioeconomic disadvantage. A Town Is Born gives the backstory behind the current trauma and dispossession, from the end of the Aboriginal frontier resistance led by Jandamarra through to the evolution of Fitzroy Crossing in the mid 1970s as a hub for Aboriginal resettlement in the region, with the demise of the pastoral regime providing the narrative’s fulcrum.

Hawke describes the original “bush outpost” of Fitzroy Crossing as having “stumbled into existence” in the late 1890s “with no clear definition of when it took on the status of a township.” For almost sixty years, the town consisted of the three “p”s – pub, police station and post office – which were later joined by the native depot. By 1965, the year before the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission’s equal wages decision, twenty-three “natives” were listed as living there, half of whom were employed.

By the late sixties, a series of evictions and walk-offs accompanying the push for equal pay and better conditions on the local stations transformed this “gross exaggeration” of a town into a collection of makeshift shelters for displaced Aboriginal pastoral workers and their families. In one notorious incident, a station manager dumped the “Christmas Creek mob” – one hundred Aboriginal workers, children and old people – on the riverbank at Fitzroy Crossing, with little money and no food, rather than, it seems, having to pay Aboriginal labourers and support their dependents.

Fitzroy Crossing struggled to cope with the sudden population explosion and the United Aborigines Mission, in conjunction with the Department of Native Welfare, set up an emergency camp of tents in response. Elder Olive Knight describes it as being like a “refugee camp,” worse than living on the stations because “people were packed like sardines”:

Hardly any room to move and there was a little space, a tiny piece of land that you can all sort of pack yourself into and there was only one toilet and one shower sort of thing. The conditions were quite poor.

At the same time, the white settlers’ binge-drinking culture was transferred to the local Aboriginal population following the easing of restrictions on access to alcohol that accompanied the receipt of citizenship rights.

A decade later, negotiations began between family groups and pastoralists to allow Aboriginal people to return to live in communities on their country on excisions of local stations. Fitzroy Crossing, which provides the nexus for this patchwork of communities, is now essentially an Aboriginal family-based town with, in Olive Knight’s words, “a strong bond that remains from the past… Grog didn’t take it away you know. It’s still there. Running right through us.”

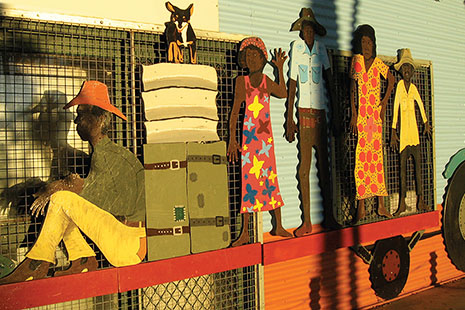

A Town Is Born was instigated by Joe Ross, a Bunuba leader in Fitzroy Crossing, as a community project that would provide “an uncensored historical account told by respected Elders” and contribute to the social and cultural sustainability of the region. Steve Hawke, writer of the play Jandamarra, synthesised the narrative by interweaving oral history accounts from elders (“the story-tellers”), who’d worked on properties in the Fitzroy Valley during the 1960s and 70s, with official records from relevant stations, missions and government departments. The book, produced by remote Indigenous publisher Magabala Books, is an attractive volume, and includes large black-and-white photos of the Aboriginal story-tellers along with reproductions of relevant documents.

Overall, Hawke’s strategy of integrating oral history with official records and photographic material is effective; the stories about the eviction of the Christmas Creek mob and subsequent conditions at the makeshift mission camps are particularly compelling. One of the book’s most interesting aspects is its depiction of the nuances and ambivalences accompanying the relationship between pastoralists and Aboriginal labourers. This period in the Kimberley’s history, memorialised – and problematised – in Mary Durack’s Kings in Grass Castles, is sometimes mythologised as the “good old days” by both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people who worked on the stations. Tim Emanuel, from the Go Go station family in the Fitzroy Valley, observes in A Town Is Born that there was an informal code, “an unwritten law that it was our station and their country.” Aboriginal people often valued the flexible work arrangements associated with station life, which enabled them to travel and practise law on country: “the spiritual fabric of life remained strong.”

A Town Is Born also explores the other side of the relationship, including conditions for Aboriginal pastoral workers that often entailed little or no pay, accommodation or healthcare, and limited or no provision of schooling for their children. Even at Go Go station, considered the yardstick of progressive standards and treatment in the Fitzroy Valley, a welfare inspector reported in 1968 that the “natives are not ill-treated, nor are they particularly well treated, receiving only the basic requirements of sustenance and accommodation.”

Hawke speculates that some older Aboriginal people remember this period fondly despite its harshness because of a universal nostalgia for childhood. At times, I felt the story-tellers could have been prodded more to reflect on their sense of nostalgia or resignation about what they had endured on the pastoral properties and mission camps. But I suspect this lack of elaboration relates to the book’s vision that the story-tellers’ accounts be left intact to speak for themselves.

A Town Is Born tells an intensely local story that will have many resonances with the histories of other remote settlements across northern Australia. Although the book’s main project is to document the Fitzroy Valley’s post-colonisation history, with a focus on pastoralism and its aftermath, it could have provided more description of contemporary life in Fitzroy Crossing to give tourists and outsiders a stronger sense of the place. That said, A Town Is Born presents a careful, readable and frequently illuminating history of a northwestern Australian town. As well as providing a community resource for Fitzroy Valley residents, it is likely to appeal to a range of outside readers, from the curious grey nomad on a Kimberley pilgrimage to anyone with a historical interest in the transition from the pastoral period to the citizenship rights era. •