Thomas Jefferson, author of America’s Declaration of Independence and its third president, was a man of the Enlightenment who believed in the authority of reason. But he never entirely abandoned the Christianity of his upbringing, and when he retired to his home in Virginia in 1809 he reconciled these two influences by making for himself a Gospel compatible with the dictates of reason.

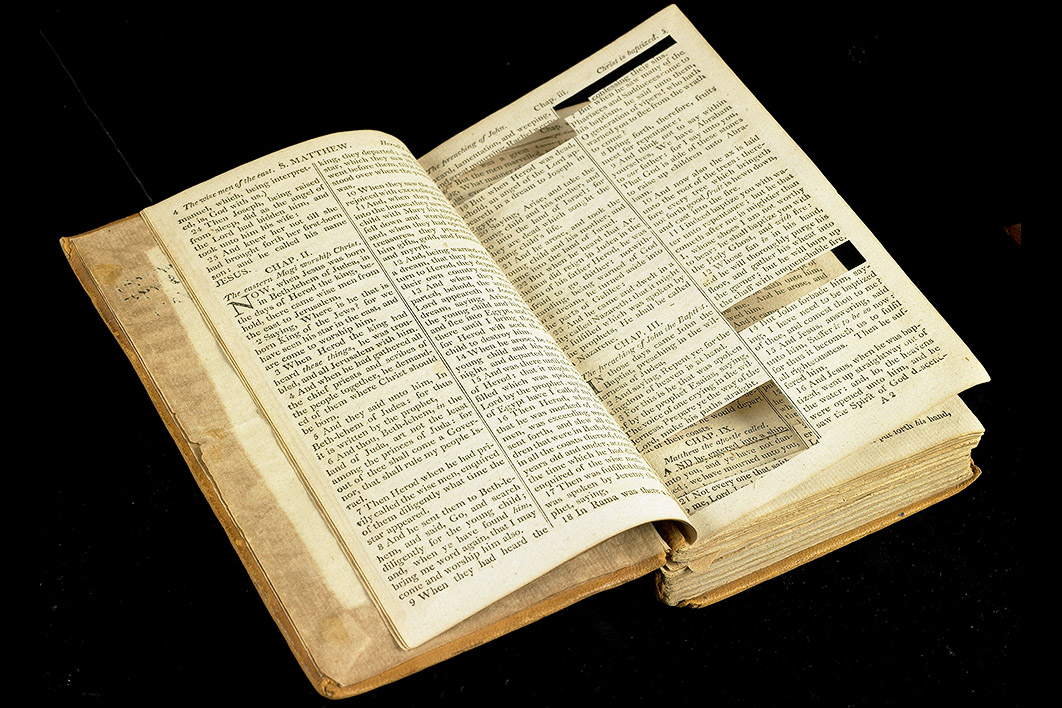

The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth — known as the Jefferson Bible — was a cut-and-paste job. Jefferson collected Bibles in English, Greek, Latin and French, cut out the passages from the Gospels that displayed “the most sublime morality ever fallen from the lips of men” and pasted them in a folio of blank pages. Left behind in the mutilated Bibles was what he called the “dross added by Jesus’s biographers.” Jefferson’s purpose, he said, was to rescue the teachings of a great moralist — superior to Socrates or Cicero — from the misinterpretations and distortions of the writers of the Gospels. “It is as easy to separate those parts,” he wrote to his friend John Adams, “as to pick out diamonds from dunghills.”

Absent from Jefferson’s Bible is any appearance of the supernatural. His Jesus performs no miracles, makes no claim to be the Son of God and forgives no sins. His birth is not heralded by angels and he is not resurrected. The Bible ends with a stone being placed in front of his grave.

In the remaining years of his life Jefferson used his Bible for bedtime reading but made no attempt to publish it, and few people knew of its existence.

Peter Manseau, a curator of American religious history in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, has written a biography of the Jefferson Bible, one in a series about the lives of great religious books. Despite its obscure origin as Jefferson’s private project, the life of this book continued well beyond his death, and in the 200 years since its birth it has undergone changes and served purposes that Jefferson could not have imagined.

Manseau relates how the Jefferson Bible was discovered, exhibited and many times published, and how it eventually became an American icon presented to members of Congress and buried along with the Declaration of Independence under the cornerstone of the memorial to Jefferson in Washington. Its existence, he says, is a manifestation of the American idea that existing materials can be reshaped into something new. Its later history shows how this reshaping has continued through more than two dozen printed editions into the twenty-first century.

Just as Jefferson believed himself to be presenting the true message of Jesus, the many interpreters of his Bible presented what they thought was Jefferson’s true purpose. The uses to which the Jefferson Bible has been put, the many editions and introductions published, reflect not only the ideological commitments of these interpreters but also the concerns and preoccupations of their times.

The Jefferson Bible came to light mostly through the efforts of Cyrus Adler, a curator at the Washington-based Smithsonian Institution, in the late nineteenth century. Recognising that a mutilated Bible in a private collection had been one of the sources of Jefferson’s clippings, he eventually discovered the Bible itself among the papers held by Jefferson’s great-granddaughter. Purchased by the Smithsonian, it became a star attraction in an exhibition of Bibles designed to demonstrate the American ideal of religious tolerance and diversity.

John Fletcher Lacey, a devout Christian and Jefferson-admirer who sat in Congress for much of the period from 1889 to 1907, credited himself with bringing the Bible out of obscurity and to the attention of the American public. His proposal to have the US government print 9000 copies for existing and future members of Congress caused an uproar of condemnation from pulpits all over the country. But his campaign was successful and private publishers were quick to take advantage of the publicity to publish their own editions. The Jefferson Bible became a bestseller.

Some editors reshaped the Bible according to their own agendas. In the 1920s Henry Jackson, a clergyman and the founder of a college of social engineering, enlisted Jefferson’s Jesus to serve his reforming aims by modernising the language of the text, adding passages that he thought had wrongly been left out, and writing an introduction that presented both Jesus and Jefferson as practical reformers of society.

Douglas Lurton, who had received a copy of the Bible from his congressman father, brought out a modernised edition in 1940 as a statement of American values in opposition to “the anti-Christian butchery of the despots of the Old World.” The Unitarian pastor Donald Harrington saw the Bible as an antidote to the fears and follies of the cold war. “We need to drink deeply of the peace found in [Jefferson’s] righteousness.” By the mid twentieth century the Jefferson Bible had become an expression of faith for many Americans. “My religion is based entirely on the so-called Jefferson Bible,” declared congressman and Baptist pastor Adam Clayton Powell.

The Jefferson Bible has been enlisted in both sides of the culture wars. David Barton, a protégé of the Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee, argues that the Bible proves that America was founded as an essentially Christian nation. The American Humanist Society produced a Jefferson Bible for the twenty-first century that included passages from the Hebrew Bible, the Bhagavad-gita, the Qur’an and various Buddhist writings — not only to prove that the same cut-and-paste operation could be performed on other religious books but also to construct a text for a more inclusive American society.

How should we assess the Jefferson Bible as a work of religion or ethics? Making judgements about its content is not Manseau’s main purpose, but he expresses doubts about Jefferson’s project of picking out the ethical jewels of Jesus’s teaching from the supernatural dross. Without the miracles, he thinks, the Gospel narrative doesn’t make sense. Jesus tells the Pharisees that it is lawful to heal on the Sabbath but does no healing. He indicates that a woman who washes his feet should be forgiven her sins but does not tell her that her sins are forgiven.

“With miracles hinted at but never delivered, forgiveness discussed but never offered, the text often has the feeling of a series of jokes without their punchlines,” he writes. “Jefferson’s Jesus stories are all set up with no pay off.”

As a philosopher I prefer to approach the Jefferson Bible not as an attempt to make Gospel stories wholly consistent with Enlightenment rationality but as a book that gives us the bare bones of Jesus’s ethical teaching. Is Jesus the greatest moral thinker of the ancient world, as Jefferson supposed? Or are the ethics of the Gospels an unsystematic and inconsistent collection of moral commandments and practical wisdom? Those who read Jefferson’s Bible must judge for themselves.

But even a cursory reading of the text reveals an important difference between Jesus’s teaching and the moral philosophies of ancient Greeks and Romans like Plato and Cicero. Jesus’s words were meant for ordinary people — women as well as men — and not merely for an educated male elite. He preached against religious laws and practices that didn’t serve human needs. Perhaps these were reasons why Jefferson, a founder of American democracy, was so deeply inspired by Jesus’s teachings. •

The Jefferson Bible: A Biography

By Peter Manseau | Princeton University Press | $44.99 | 232 pages