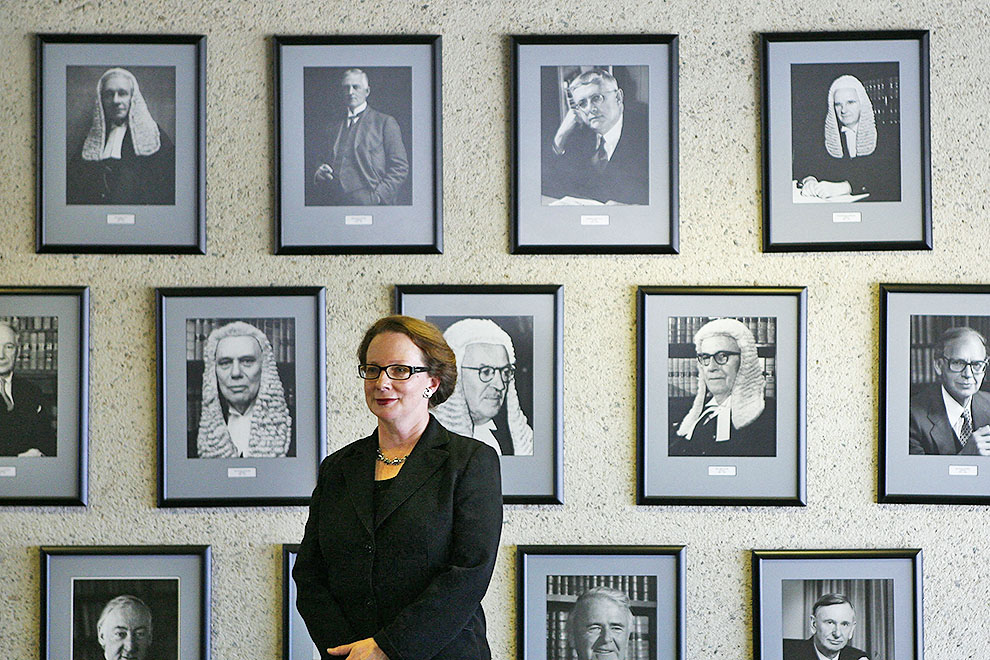

Australian women waited over eighty years for the first woman to sit on the bench of the High Court of Australia. Now, three decades later, a particularly resilient glass ceiling has been shattered with the announcement that Susan Kiefel will preside as chief justice, filling the vacancy created by Robert French’s retirement. The vacancy opened up by her appointment will be filled, in turn, by the Federal Court’s James Edelman.

When Her Honour takes her seat as Australia’s thirteenth chief justice, she will preside over a court composed of four men and three women, a balance that Justice Mary Gaudron could hardly have imagined when she was appointed in 1987 and one that would have been entirely unimaginable in 1903 when the High Court was formally established as an institution.

Nothing in the Australian constitutional framework calls for diversity in judicial appointments, but it is clear that political expediency means there is some political currency in adopting more inclusive appointment practices. But will this move disrupt the ingrained notion that judging is the preserve of men? Certainly, the level of speculation before Her Honour’s elevation suggests that the idea of a woman sitting at the peak of Australia’s judiciary was no longer as inconceivable as it once might have been.

Her appointment, in addition to marking a significant personal career milestone, certainly makes an important symbolic statement about women’s access to legal authority. It should also prompt us to take stock of how far we have come in terms of judicial diversity and to think about the path ahead. What difference might a woman chief justice make and what does this appointment mean for the politics of gender inclusion and judicial diversity?

Judicial appointments and gender diversity

Women judges have been appointed to the High Court in more recent years with what could almost be described as a degree of regularity. Yet their appointments have largely been framed as happy coincidences rather than as part of any commitment to securing a more diverse judiciary. This most recent appointment follows that trend. Despite representing an important milestone in Australia’s constitutional history (and a triumph for the politics of diversity and gender equality), it serves as a reminder that so long as our appointment processes lack transparency and fail to formally enshrine the importance of diversity, such gains will remain precarious.

The High Court of Australia has always been politically and constitutionally significant, and so too have the judges appointed to it. In legal terms, the government is largely unfettered in making these historic appointments: there are no special provisions regarding the appointment of the chief justice and – beyond specifying that justices of the High Court “shall be appointed by the governor-general in council” – the Australian Constitution provides little direction regarding appointment processes.

Slightly more guidance about the consultation process and qualification of justices is found in the High Court of Australia Act 1979 (Cth), which provide s that an appointee must be a judge or enrolled as a legal practitioner for more than five years and that the attorney-general shall consult with state attorneys-general. In practice, the Commonwealth attorney-general generally directs the process, and in most cases presents a nominee to cabinet. Should cabinet accept the nominee, the person is then formally recommended to the governor-general for appointment.

Curiously, given the breadth of power afforded to the government of the day in making judicial appointments, High Court appointments have generally been relatively uncontroversial. The absence of obvious partisan battles in Australian High Court appointments stands in contrast to, for example, the fraught confirmation processes that Supreme Court nominees are subjected to in the United States. These distinctions notwithstanding, judicial appointments cannot be anything other than political; they are made by those in possession of the highest levels of political power and they clearly have political consequences.

Appointments may be said to be explicitly political, or at least more overtly political, when the government appoints those they regard (or whom others regard) as sympathetic to their broad political outlook. Appointments from the executive are not unheard of, and the controversies surrounding the appointments of Justice Lionel Murphy and Chief Justice Garfield Barwick, to cite just two examples, have been well documented. Although there has been (albeit tongue-firmly-in-cheek) speculation about Attorney-General Brandis appointing himself, there is now probably very little taste for overtly political appointments that reinforce the less-than-absolute separation of powers.

But the lack of transparency around High Court appointments means that we know little about what informs the decision-making. We do know that certain considerations have emerged as legitimate in making appointments, whereas others have been seen as less legitimate. These legitimate considerations are imbued with certain values and assumptions about what matters in selecting our judges. An appointee’s state of origin is sometimes raised as a valid consideration, for example, whereas gender, race, sexuality, ethnicity, and even age are seen as illegitimate considerations.

The point is well illustrated by the political rhetoric that attended Justice Kiefel’s initial appointment to the High Court in 2007. As the appointment followed the appointment of Justice Susan Crennan two years earlier, a journalist noted that this was a “historic occasion” because it was the first time two women would be sitting on the bench, and asked the attorney-general whether her gender was taken into consideration. Attorney-general Philip Ruddock denied that gender was a relevant consideration in the appointment, stating that “any suggestion that this appointment was to secure two female appointments would be quite wrong.” Ruddock assured the journalists that, given Her Honour’s eminence and the fact that “she is a woman of extraordinary attainment,” this appointment, like the appointment of Justice Crennan before her, was made on the basis of merit alone:

It is a factual matter that there are five male judges and now there’ll be two female judges. But they are both people who were appointed on their merits, worthy of the appointment and a great credit to the profession.

But in response to another question relating to “her being a Queenslander replacing another Queenslander,” Ruddock did concede that he did “look at these matters.” But he was quick to play down the relevance of her state of origin by again pointing to the fact that the decision was “merits-based.”

Ruddock’s appeal to the terminology of merit suggests that the government’s strategy was to signal to its supporters that although it was appointing a woman, there was no tokenism or “progressive” or “gender” politics at play and that it could be relied on to appoint suitable candidates. Perhaps more tellingly, his remarks serve as a reminder about the breadth of the attorney-general’s discretion: we really do not know what matters he or she has considered in determining the best person for the job. It is assumed, of course, that certain matters might be taken into account (state of origin, legal expertise and judicial approach) in settling on a nominee. But nothing compels the decision-makers to consider certain matters or to communicate any details about the decision-making process.

Calls to reform High Court appointment practices to improve not only diversity, but also transparency and accountability, are certainly not new. I have argued elsewhere that reforms to the judicial appointment process – especially those designed to enhance judicial diversity by explicitly including it as a matter to be considered among others in the appointment process – will only be plausible if the relationship between merit and diversity is recast. Alluding to the subjective nature of merit, Harry Hobbs has argued that the ambit of discretionary powers afforded to Australian attorneys-general “is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain.” He explains that measures implemented by then attorney-general Robert McClelland to improve transparency in Federal Court appointments now appear to have been abandoned. Although McClelland’s reforms didn’t extend to the High Court in any case, their abandonment underscores the need to formalise reforms rather than rely on the political whims of the day.

For a brief period in 2015, following Justice Susan Crennan’s retirement (and replacement with Geoffrey Nettle), only two women were serving, but since then a near-equal gender balance has returned. At the time, Kim Rubenstein suggested that the High Court should always comprise at least 40 per cent of each gender. Emphasising the importance of a judiciary that reflects the society it serves, she made the important argument that gender should be “one of the meritorious matters that must be considered in the appointment process.”

Of course, quotas are not the only formal means of achieving diversity. As Andrew Lynch has argued, a more representative judiciary might also be achieved by adopting processes of judicial appointment that express diversity as “an aspiration underpinning those processes.” Developments in Britain, Canada, New Zealand and other jurisdictions have made explicit that certain matters (gender, race, ethnicity or linguistic background, for example) might be considered as part of the appointment process.

Attorney-General Brandis’s announcement that Justice Kiefel will be elevated to chief justice follows a familiar pattern in emphasising that this was a merit-based decision, therefore assuaging any concerns that it might have been a “gender-based appointment.” The attorney-general was keen to point out that every step Justice Kiefel has taken has been a “step that she took on merit.” When he announced her replacement, Justice James Edelman, there was curiously no retreat to the terminology of merit. Of course, His Honour’s achievements were canvassed – with some emphasis on their particularly precocious nature, given that His Honour is forty-two years old.

Justice Kiefel’s appointment is a politically astute one for the government. Given her status as the second most senior puisne judge and her contributions to the court to date, this is not a radical appointment. In addition to having already appointed more women justices to the High Court than the Labor Party have, the Coalition can now boast of having appointed the first woman chief justice of the High Court.

It is perhaps important to acknowledge, and give context to, the broad ideological differences between the Coalition and the Labor Party regarding measures to advance women’s political participation. Although both major parties’ policies concerning women and the prospects for women parliamentarians have often been problematic, it is noteworthy that the Labor Party formally supports affirmative action in preselection for women, whereas the Liberal Party does not. Of course, there are important differences between political and judicial power, and I don’t want to suggest that any appointments to the High Court have been the result of such a policy. But the politics around the legitimacy of such measures in the legislative branch is significant in that it illuminates the precarious and contested value of gender diversity.

In the current political context, notwithstanding the different views about measures to advance women in the legislative branch, there seems to be little space for a discussion about the importance or desirability of diversity in appointments at the peak of Australia’s judiciary. While we are frequently reminded that merit must be the guiding principle in making alljudicial appointments, discussions (and sometimes doubts) about an appointee’s merit are more likely to come to the fore when that appointee is a woman. This arguably reflects what appears to be a national aversion to “tokenism” or affirmative action, even when no such policy has been invoked. Those who demand that appointments be made on merit without any other consideration discount the subjective nature of merit itself. What counts as meritorious is determined by those already in positions of power and privilege; and as Margaret Thornton has argued, their claim “to produce an objective ‘best person’ is a rhetorical claim designed to maintain the judiciary as a gendered regime.”

Granted, criticism about current High Court appointment practices (and the disinclination of successive governments to consider reforms to appointment processes) needs to be tempered with the reality of what have been clear gains for women. Space had to be made for women on the highest judicial benches simply because getting women into positions of judicial authority was a departure from the overtly gendered regimes of the past. It might be countered that if this strategy is working (and the current composition of the High Court certainly points to marked progress), then there is no need to formalise any measures to secure a more diverse judiciary.

But we only need look at the experience in legislative and executive branches to know that hard-won gains in improving the representativeness of our public institutions are by no means guaranteed – they might stagnate or even go backwards. The OECD recently acknowledged that the gender balance in the Australian Senate (38.2 per cent women) is among the best in the world, but noted that the number of women in the House of Representatives has remained relatively low (26.7 per cent women). Meanwhile, the number of female federal ministers (17.2 per cent) revealed not only that Australia has made little progress in gender diversity but also that it is lagging behind other OECD countries on this indicator. These figures were compiled when Tony Abbott was prime minister and will have improved as a result of Malcolm Turnbull’s appointment of a number of women to his front bench. But they nonetheless underscore the precarious nature of gains in gender diversity – particularly when those gains rely on the actions of politicians.

Why does diversity (still) matter?

Two broad streams of argument have been used to justify the appointment of women to judicial roles – difference and equality. Arguments on the basis of difference contend that the quality of justice available will be improved because women offer something different, perhaps by “speaking in a different voice” or by bringing an “ethic of care” to the judicial role. Arguments premised on equality contend that the “principle of equity requires that women have an equal opportunity to participate in public decision-making institutions and that their absence undermines the democratic legitimacy of those bodies.”

Arguments based on principles of equality are often eager to distinguish between the need for a diverse judiciary and the need for a representative judiciary. While diversity is desirable, they contend, the notion that judicial officers should represent the interests of their gender (or class or race) is objectionable because it misconstrues the very nature and function of the judiciary as an institution that is unresponsive to political pressure.

The stakes wagered on women’s access to legal authority have been particularly high. Some feminist legal theorists hypothesised that women judges would be the panacea to law’s gender-blindness. But the arguments that women judges make a difference (in terms of their judicial approach), while appealing, have been difficult to sustain in practice. Women judges have not always been as different from men as predicted, or different in the ways that were originally envisaged.

As women began to be appointed to the judiciary in larger numbers throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, the scope to assess women judges was expanded, not only by empirical studies but also by assessments of the publicly expressed views of women judges themselves. Some women judges in other jurisdictions have been disinclined to embrace the notion that they speak in a different voice, although others have embraced a version of difference, or even feminist judging.

With the exception of Justice Gaudron, women judges appointed to the High Court have mostly eschewed an identity as “women judges,” or at least avoided talking about the possible relationship between gender and judging. If history is any indication, it is likely that our new chief justice will follow this well-worn path.

It remains to be seen what kind of contribution Chief Justice Kiefel will make to the High Court. Her extra-curial comments indicate that the Kiefel court, like the French court before it, might be marked by consensus. Whether she evidences a growing willingness to reflect on the changing role of women and the law (like Justice Crennan before her), and the frustrations associated with the gendered ways in which her legacy might be received, will also remain to be seen.

Feminists are on safer ground premising their arguments on a need for diversity so that the judiciary is composed of individuals who are more representative of society as a whole. That is not to say that feminists have abandoned the interrogation of the gendered nature of the law. Rather, in recognition of the restraints of legal formalism, we have seen a retreat from the idea that the appointment of women judges will disrupt the masculinist nature of legal reasoning, to the idea that feminist judges might be best equipped to bring such perspectives to bear.

This is not to say that the gender or lived experienced of a judge won’t inform their decision-making in ways that reinforce the importance of diversity. (Why would we insist upon multi-member appellate courts if we didn’t accept the idea that law is a human endeavour?) Rather, it is to avoid essentialising women and conflating “woman” and “feminist.” Justifications for appointing women judges are therefore now far more commonly couched in terms of equity or representation rather than difference, because, as Kate Malleson has explained, “their persuasiveness or validity is not determined by what women do on the bench.”

Where to from here?

The gender dynamics on the High Court have thus far been carefully crafted. No woman has ever replaced another woman – lest anyone get the idea that there are seats reserved for women. Nevertheless, at least for now, the presence of women as members of the court seems secure. Assuming Chief Justice Kiefel stays on the bench until she is seventy years old, a woman will serve as chief justice until 2024. If Justice Michelle Gordon stays on the bench until her mandatory constitutionally required retirement, we are guaranteed at least one woman until 2034. United States Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s response to queries about when there will be “enough” women judges is salutary:

So now the perception is, yes, women are here to stay. And when I’m sometimes asked when will there be enough [women on the Supreme Court], and I say, when there are nine, people are shocked. But there’d been nine men, and nobody’s ever raised a question about that.

The point is a powerful one because it reveals how normalised an all-man bench is, especially when juxtaposed against the seemingly fantastical idea of an all-woman bench. The current visibility of women on the bench makes an important symbolic statement about women’s admission to legal authority in Australia. But this appointment does not negate the need for continuing conversations about the importance of diversity or for amendments that would properly enshrine the value of diversity into the formal appointment process.

We are very fortunate that the Australian judiciary has fulfilled its role mostly with distinction and without controversy. But this good fortune should not deter us from bringing appointment practices into the twenty-first century. Appointments that undermine the homogeneity of the High Court are steps in the right direction, and disrupt the notion that judging is the preserve of men. But with no formal recognition of the importance of diversity in appointments, these steps remain at the whim of the government of the day. Diversity and merit are not mutually exclusive. Diversity can and should have a legitimate and meaningful role in appointment practices. But if the utterances of the politically powerful are to be taken at face value, diversity does not inform their decision-making processes. In fact, the lack of transparency around the process and the absence of criteria upon which these appointments are made leave us in the dark about what matters are taken into account.

Once we accept that a more diverse judiciary is a better judiciary, we are able to have important conversations about the scope and content of reforms, which might then secure a truly diverse judiciary. And then, for feminists, there might even be space to think about strategies for securing the appointment of judges who are not only aware of the importance of equality and the gendered nature of law, but also willing and able to articulate that awareness. •

This article first appeared in AUSPUBLAW, the Australian Public Law Blog.