Virginia Haussegger is an angry woman. Back in 2010 she published a book called Wonder Woman: The Myth of Having It All. It began by describing her anger at being childless, at having a dream job and still feeling unfulfilled, at feminism’s promise that she could have it all when that was “a load of crap.”

Her second and latest book, Unfinished Revolution: The Feminist Fightback, begins with shared anger, the anger that brought more than 12,000 women to protest outside Parliament House in March 2021. “Anger, frustration, indignation — women across the nation were awash with it… a hot, caustic, female furore” galvanised by “violence and sexual assault.”

When I read Wonder Woman I doubted whether her anger was justified. Reading Unfinished Revolution I have no doubt the anger that fuels it is totally appropriate to the situation in which we women find ourselves today, in what Hausseger calls our “New Now.” I share the despair she feels when she watches TV news bulletins cataloguing the loss of hard-won women’s rights internationally and, locally, “gut-wrenching stories of violence against women.” In fact I can’t bear to watch the news. And according to Haussegger that makes me part of the problem.

The problem is entrenched misogyny, global and local. The solution she urges is revolution — political and social revolution — and, as an essential condition for these, personal revolution. In telling “the story of women’s revolution and feminist fightback in Australia” Haussegger is trying to open her readers’ hearts and minds to the rush of feeling the feminists of the 1970s described as liberation: the understanding that comes with seeing “the systematic patterns of women’s oppression.” In the words of Julia Ryan: “We had no choice. Once our awareness was heightened and our consciousness raised, we had to change.”

I am part of the problem in another way too: as a feminist I have always been a reformer. I have worked inside and out of universities to change laws and regulations to give women equality with men. Haussegger insists on good authority that reform is not the solution; equality is not enough. She cites Germaine Greer: “The idea of women’s equality threatened nobody… the question of liberation was far more disturbing.” And Elizabeth Reid, telling the United Nations in 1975: “We can no longer delude ourselves with the hope that formal equality, once achieved, will eradicate sexual oppression — it could well merely legitimate it.”

Haussegger tells her story backwards. Part 1 considers “Our New Now”; part 2 steps back a few years to the March4Justice; part 3 leaps back fifty years to the birth of Women’s Liberation in Australia; and part 4 chronicles the achievements of Elizabeth Reid in Australia and internationally. I found this backward rush through time disorienting, but less historically driven readers may not be bothered. Either way, there are fascinating stories here, celebrating revolutions and revolutionaries small and large.

Haussegger has done her research thoroughly, supplementing documentary archives, memoirs and biographies with her own interviews. Some of her subjects will be well-known to most of her readers, others less so. Her account of the 2021 March4Justice foregrounds Janine Hendry, whose tweet kickstarted the movement:

Ok here’s my thought — is it possible to form a ring of people around the perimeter of Parl Hse? Then all of us extremely disgruntled women could travel to Canberra on March 8 and form a ring linking arms with our banks turned towards the parliament and stand in silent protest.

The rest is history — though the protest that erupted was far from silent.

For me the most moving section of the Unfinished Revolution is the final one, telling the story of Elizabeth Reid. The story has been told before, but this account is immediate and empathetic, drawing on personal encounters and interviews with Reid.

Haussegger follows Reid’s trajectory from her appointment as Gough Whitlam’s “Supergirl” — the press mockery was immediate and constant — through her role in scheduling the 1975 UN International Women’s Year, the massive funding of women’s projects in Australia to celebrate that year, her speech at the Mexico World Conference on Women educating UN delegates on sexism and patriarchy, the brutal press reactions back in Australia to the Women and Politics Conference, and her subsequent removal from her position as adviser to the PM.

Reid responded by retiring, and leaving the country. Trying to change the system from within was, she said, “extraordinarily destructive and extraordinarily harmful. I think the price is too high for many…”

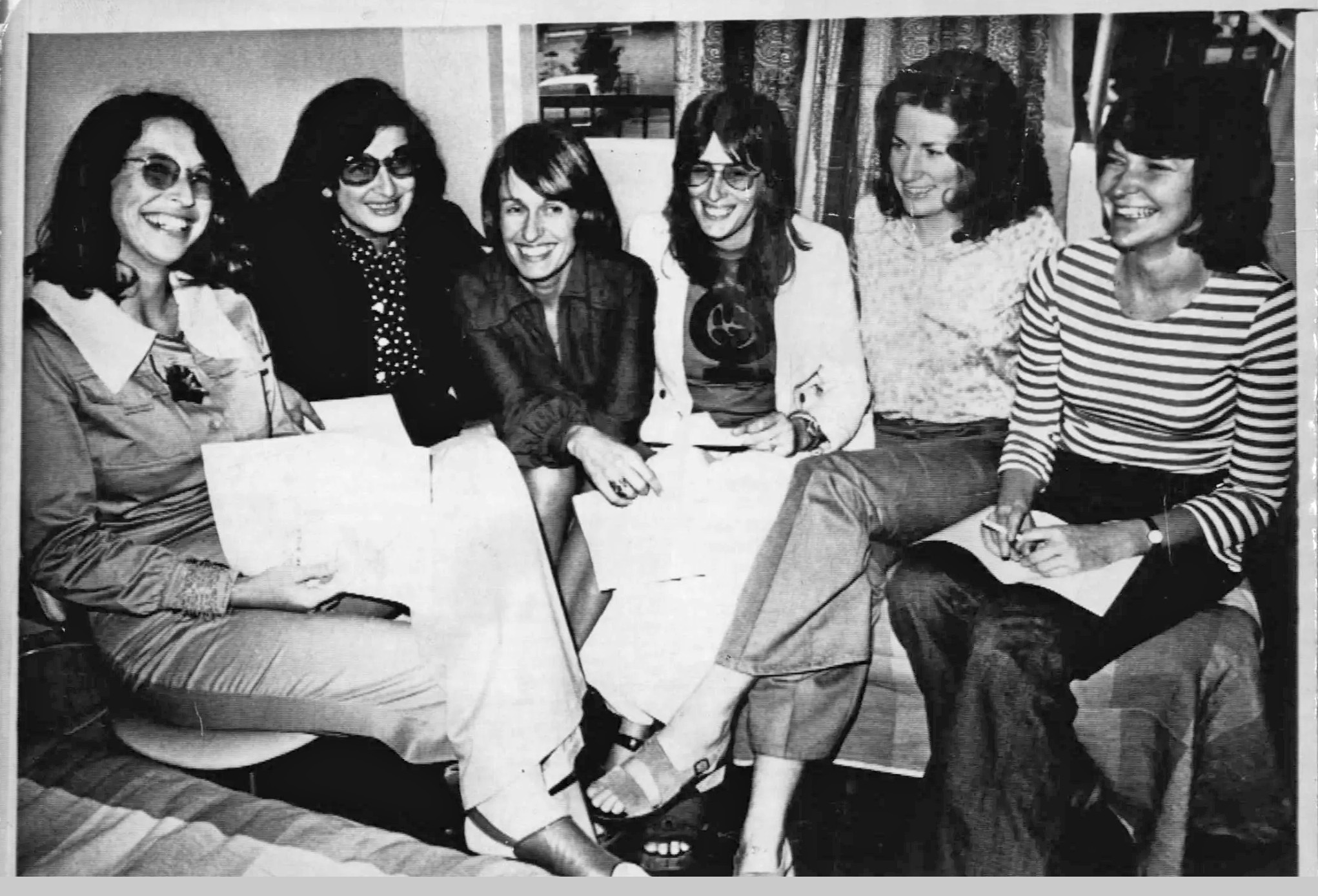

But the Unfinished Revolution is not all anger and despair. There is joy in this book, and hope. The joy is in moments of sisterhood: a bunch of “older feminists” dancing to Helen Reddy’s “I Am Woman” at the March4Justice demonstration; Women’s Liberation Movement members discussing their abortions “in gruesome detail” when they suspected ASIO was listening in; the candidates for the job of PM’s adviser putting out a joint press release to confirm their commitment to working together whoever got the job.

The hope is in the successes Haussegger catalogues: legal and administrative reforms achieved during the Whitlam and Hawke–Keating eras; reforms to workplace practices and a huge influx of women MPs into Parliament in the wake of the March4Justice. She finds that Australian women are well-placed to fight the global anti-women backlash.

But still, she argues, reform is not enough. In her concluding chapter she declares that “until the world has eradicated all forms of sexism and misogyny… until then we will need to fight for liberation.” She cites Elizabeth Reid: “We must adopt a true revolutionary consciousness… moving past policy reform and gender equality… New challenges demand… a revolution in our heads and hearts… It’s time.”

This should be stirring stuff, and I hope this book finds readers ready to be stirred. But I confess I put it down with my heart unmoved. My head needs to know how this revolution will actually work within Australian culture and institutions. •