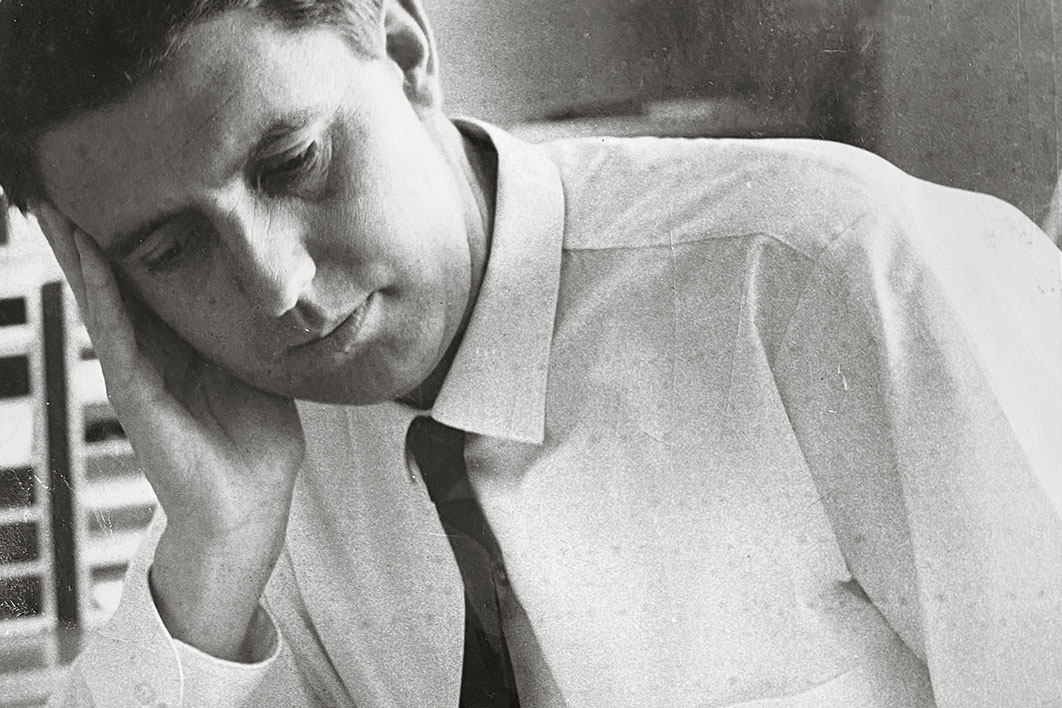

Michael Cannon is one of those figures whose books, mainly acquired second-hand, began multiplying on my shelves almost without my being aware of who he was. The first of his I owned, The Land Boomers, contained no biographical information at all about its author. His trilogy of Australia in the Victorian Age offered cursory references to decades as a “journalist and historian”; likewise his six edited volumes of the Historical Records of Victoria. Only That Disreputable Firm, his history of plaintiff lawyers Slater & Gordon, included an image: a close-cropped dust-jacket photo, passport-style, revealing a genial face with a salt-and-pepper beard.

I only once had the opportunity to speak to him, in 2014, for a book I was writing. Cannon was eighty-five but busy, still busy, excited to be editing a new collection of writing by “The Vagabond,” the versatile nineteenth-century journalist John Stanley James. He talked expansively of other projects he had planned. He reminded me of the conductor Sir Charles Mackerras, who as an octogenarian would sign contracts to conduct orchestras with the notation: “Will play if alive.”

Busy Cannon remained. When he died on 24 February this year, he was at work on a memoir, Cannon Fire, which has now been published by Melbourne University Press. It shows no sign of hurry. Rather, it has the tone of someone for whom writing was not just a pleasant pastime but also far preferable to any other activity. It covers almost exactly the same period of Melbourne and Victorian history as Cannon’s near contemporary Geoffrey Blainey traversed in Before I Forget (2019). I can pay it no greater tribute than by stating that it does not suffer by comparison.

Cannon, it shows, did not so much hide behind his work as fully inhabit it, living out a set of abiding interests in social, media and institutional history. He was mainly self-educated, another graduate of the school of Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopedia, and self-taught, in the newsrooms of Melbourne, Sydney and London.

As books displaced daily reporting as a proportion of his output, he continued writing history with a journalistic sensibility. That hybrid status has made him difficult to classify: he gets one paragraph in The Oxford Companion to Australian History and goes unmentioned in A Companion to the Australian Media. Still, when the effect worked, it was electrifying. The Land Boomers, still the definitive text on the period of Melbourne’s halcyon 1880s and hungry 1890s, reads as though composed contemporaneously in a succession of thrilling scoops.

In this memoir, Cannon describes the thrill of disinterring trunks of salient Crown Law Department documents from the State Library’s basement.

As I unpacked them in dim light, excitement began to take hold of me. Here were details of the dirty doings of most participants in the land boom — all the chief financiers like W.L. Baillieu, the sly solicitor Theodore Fink, and crooked politicians like James Munro and Thomas Bent. The archives had no photocopying facilities at the time so week after week I painfully transcribed every relevant detail of all the ambitious individuals and their fraudulent company flotations.

Extraordinarily, we learn, the Sydney Morning Herald declined to publish extracts from the book: given the archaic defamation laws in New South Wales, which offered descendants recourse for libels of their ancestors, the new light Cannon shed on the period was too salacious. Sydney booksellers were circumspect too. Melbourne took a more robust attitude: Baillieu, Fink and the like might have eluded their importunate creditors but not, in the end, the footslogging penman.

Cannon’s particular voice — readable, curious, discursive, anecdotal — means his work sits somewhat to one side of academic history. He was a low-temperature writer with a moral rather than a political centre who wrote for readers rather than colleagues or causes.

In that sense, Cannon took after both his parents. His mother Dorothy was the daughter of Monty Grover, doyen of tabloid editors, who herself “crackled with obsessive energy” as a pioneering journalist on the Morning Post and the Argus: it was she who obtained her son his first job as a copyboy on the latter paper.

Yet Cannon paints perhaps an even fonder portrait of his “simple, kind-hearted, unfortunate” father Arthur, whom Dorothy met when he was a ship’s wireless operator: “My middle-aged father, sweat-stained grey Akubra planted squarely on his head, pipe clamped in his mouth, remained at heart a simply country bloke.”

There is a particular poignancy to Cannon’s description of the end of his idyllic rural childhood, ushered in by Robert Menzies’s declaration of war: “War to me was a glorious manly affair. So when I looked around at the adults, I could scarcely believe what I saw. Tears were rolling silently down their faces, women and men alike. Never before had I seen grown men cry. I hadn’t known they could cry. But they had realised what I had not: that the happy times were over.” He watches his laconic father grow more so:

My father gave me some parting advice before he went to the RAAF training camp. “Never be beholden to anyone,” he told me gravely. This meant, he said, that you should never accept favours or assistance from anyone if you could possibly avoid it. In other words you had to learn to stand on your own feet. This was the longest talk I ever had with him. Aged eleven, I would mull over his words and eventually agree that they formed a sensible philosophy of life.

But when Dorothy at length abandons Arthur, Cannon is too callow to understand: “Only my poor old dad tried to discuss the situation with me. ‘I want you to know that I’ve never loved anyone but your mother,’ he once told me, on the verge of tears. With the careless brutality of youth, I muttered something to the effect that, ‘These things happen — you’ll find someone else.’ He simply got up and walked away.” On his deathbed, Arthur says simply, “It’s goodbye, son.”

A prodigious, indiscriminate reader particularly inspired by H.G. Wells’s Outline of History and Science of Life, Cannon junior was not much of a student at not much of a school: his history master’s observation that he had “a liking for startling views” was not a commendation. With his headmaster, however, Cannon developed a curiously simpatico relationship: “He has imagination,” the older man wrote, “and if he could regain the enthusiasm of childhood and keep it through the experiences of manhood, he might have success as a writer.”

He was indulged also by Keith Murdoch, via a family friend, who enjoyed Cannon’s response to a question in his job interview for the Herald. “Tell me, young man, are you a c-c-communist?” asked Murdoch. “I used to be, sir,” the nineteen-year-old Cannon replied helpfully. “But that was when I was young.” Murdoch laughingly hired him, whereupon Cannon went straight to a milliner in Flinders Street to equip himself with a pork-pie hat.

For all his decades in the trade, however, Cannon concedes that he was a very loose fit for journalism: “As a journalist supposedly attuned to public tastes, I was pretty much a failure.” Cannon Fire is unusual in the annals of journalistic memoir in that the newsroom anecdotes take second place to Cannon’s adventures as a freelance roustabout and wannabe mogul, notably at Henry Drysdale Bett’s Radio Times, antecedent of the Age’s durable Green Guide.

Cannon is seen flitting from one quixotic endeavour to another — licensing the American satire magazine Ballyhoo and domestic bible Family Circle; working for Sports Novels, a magazine publishing fiction with sporting themes; starting Science Fiction Monthly, Australia’s first sci-fi magazine; publishing Tele View even before television’s Australian advent. A copy of his booklet How Television Works would be given to every purchaser of a set made by Electronic Industries.

The ems and ens of printing absorbed him every bit as much as the p’s and q’s of writing: perhaps his most successful venture was Fashion News, an independent industry journal produced on a leftover press from the defunct Argus. He had a short-lived gig as Cyril Pearl’s right-hand man attempting to domesticate Truth and the Sunday Mirror for Keith Murdoch’s son Rupert, which ended predictably badly, and succeeded Peter Ryan as “Melbourne Spy” for Nation, which suited him rather better.

Cannon’s debt to Arthur is more discernible when he writes about his personal life. His first wife took her own life after they had been married for four years; of his second marriage, he decides “not… to write much more about it, or the anguish caused on both sides.” His children are well loved but not conspicuous. He condemns himself as an “overambitious idiot… concentrating too hard on my work, not devoting enough time to my family, and excusing myself with the notion that to support them financially was enough.” But he repeats the effect in his memoir, leaving his heart barely reachable, save in evoking the love of his work. It was worth loving. •

Cannon Fire: A Life in Print

By Michael Cannon | Melbourne University Press | $39.99 | 256 pages