Late last week, North Korean foreign minister Ri Yong-ho told reporters at the United Nations that Pyongyang might launch a nuclear missile test, exploding a hydrogen bomb over the Pacific. He was responding to Donald Trump’s latest threat to destroy North Korea, and North Korean president Kim Jong-un’s promise to unleash the “highest level of hard-line countermeasure in history” against the United States.

Ri’s declaration is the latest contribution to an unprecedented war of words between Washington and Pyongyang. But if the North Koreans were to carry out “the most powerful detonation of an H-bomb,” in Ri’s words, it wouldn’t be the first time that a thermonuclear weapon has been launched by missile to detonate over the Pacific.

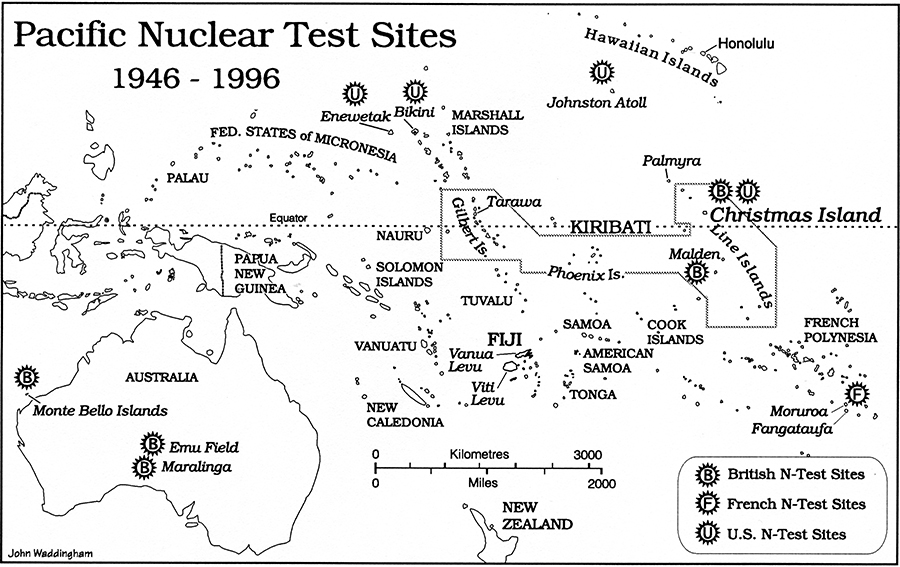

Fifty-five years ago, in the lead-up to the Cuban missile crisis, the United States launched a series of missiles from Johnston Atoll in the central Pacific, detonating hydrogen bombs that lit up the sky across the Pacific. Washington had already conducted atomic and hydrogen bomb tests in the area: sixty-seven of them between 1946 and 1958 on Bikini and Enewetak Atolls in the Marshall Islands.

In 1962, after a brief moratorium on nuclear testing, president John F. Kennedy pushed ahead with this further series of tests, just in time to avoid the terms of the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, which ended nuclear testing in the atmosphere by the United States, the Soviet Union and Britain.

Map by John Waddingham

Operation Dominic, the 1962 series, involved atmospheric nuclear tests on Christmas (Kiritimati) Island in the British Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony (today, the Pacific nation of Kiribati). Rocket launches codenamed Operation Fishbowl were made from Johnston Atoll. The first phase of the US program was conducted in a rush. Between 25 April and 11 July 1962, twenty-four atmospheric nuclear tests were conducted at Christmas Island, with weapons dropped from US aircraft.

In October 1962, five more airdrops were detonated in the vicinity of Johnston Atoll, a US possession located between the Marshall Islands and Hawaii. Johnston (known to the indigenous Kanaka Maoli people as Kalama) had been claimed for the Kingdom of Hawaii in July 1858, with the support of King Kamehameha. With the US takeover of Hawaii in 1898, Johnston effectively became a US possession, although the Territory of Hawaii continued to claim jurisdiction over both Kalama Island and neighbouring Sand Island well into the twentieth century.

Johnston Atoll had first been used for US nuclear missile tests in 1958. Two rocket launches from Johnston, codenamed Teak and Orange, both involved 3.8-megaton explosions from missile-borne nuclear warheads.

The Dominic series included five successful attempts to loft rockets into the atmosphere from Johnston Island and create high-altitude nuclear air bursts: Starfish Prime (8 July), Checkmate (19 October), Bluegill Triple Prime (25 October), Kingfish (1 November) and Tightrope (3 November). These rocket-launched tests, collectively designated Operation Fishbowl, were designed to study the effects of nuclear detonations as defensive weapons against incoming ballistic missiles.

The 1.4-megaton high-level explosion from Starfish Prime lit the sky from Australia to Hawaii, causing an enormous electromagnetic pulse that put out streetlights in Honolulu, 1300 kilometres away. The blast pumped radiation into the Van Allen belts, destroying or seriously degrading the orbit of seven satellites.

Not all the Fishbowl tests went smoothly. The successful operations were preceded by a number of aborted nuclear missile launches from Johnston, including three that caused the plutonium contamination that still lingers on the island today.

The first failed test, Bluegill, was aborted on 2 June 1962 when radar lost track of the Thor missile carrying the warhead. Range safety officers ordered that the missile and warhead be destroyed.

The next Starfish test on 19 June led to massive contamination of Johnston Atoll. The launch was aborted just one minute into its flight, and a self-destruct order blew the missile apart at about 30,000 feet. Large pieces of radioactive debris (including pieces of the booster rocket, engine, re-entry vehicle and missile parts) fell back to the island.

In 2000, the impact of this test was assessed by the US Defense Threat Reduction Agency, which conducted the Johnston Atoll Radiological Survey, or JARS:

More debris landed in the surrounding waters and on adjacent Sand Island, where residual plutonium from the test device was found. A large collection of alpha contaminated scrap was isolated during the initial clean-up… It is likely that some portion of the plutonium was pulverised and consequently dispersed in the winds occurring between the destruct altitude and the ground and thus did not contribute to contamination at Johnston Atoll. It is, however, also likely that residual plutonium, in addition to that recovered from Sand Island, fell into the waters of Johnston Atoll.

The most serious contamination came in July 1962 as a result of the test codenamed Bluegill Prime. After ignition, but before the rocket had lifted off, officials destroyed the rocket by remote control because of a malfunction on the launch pad. The JARS reports that the explosion of the Thor missile scattered debris in all directions:

Plutonium material, mixed with the flaming fuel, drained into trench cables and was carried away in the smoke from several fires. This resulted in a deposition of alpha contamination on the launch pad complex that represented a major contamination problem. Contaminated debris was scattered throughout the wire-enclosed pad area and neighbouring areas. Metal revetment buildings were highly contaminated with alpha activity.

Burning fuel flowing through cable trenches caused contamination on the interior of the revetments and all equipment contained therein. Fuel, which spilled and flowed over the compacted coral surrounding the launch mount and revetments, resulted in highly contaminated areas. Prevailing winds at the time of the destruction caused general contamination of all areas downwind of the launch mount.

In an effort to continue with the testing program, US troops were sent in to do a rapid clean-up. The troops scrubbed down the revetments and launch pad, carted away debris and removed the top layer of coral around the contaminated launch pad. The plutonium-contaminated rubbish was dumped in the lagoon, polluting the surrounding marine environment. The JARS report politely notes:

Sea disposal of radioactive waste for control of the radiological hazard was then considered expedient and proper… [T]here was no effort made to analyse the magnitude and extent of the radiological hazard resulting from the destruction of a nuclear device on a launch complex.

At the time of the Bluegill Prime disaster, the top-fill around the launch pad was scraped by a bulldozer and grader. It was then dumped into the lagoon to make a ramp so that the rest of the debris could be loaded onto landing craft to be dumped out into the ocean. An estimated 10 per cent of the plutonium from the test device was in the fill used to make the ramp. The ramp was covered during later dredging to extend the island. (The lagoon was dredged in 1963–64, with sediment used to expand Johnston Island from 220 acres to 625 acres.)

According to the JARS report:

Much of these [contaminated] sediments may have been incorporated back into the islands in the 1964 dredging and filling work, and thus much of the plutonium contamination from Bluegill Prime may have been redeposited on the island. Any contamination not redeposited on the island through dredge and fill still contaminates the lagoon.

The Bluegill Prime disaster seriously affected the health of US Naval Air Force personnel who were present at Johnston Island. Crew-member Michael Thomas reported that the flight crew and ground support staff were trapped on the island following the destruction of the nuclear warhead.

In later years, the squadron members present during that episode suffered an 85 per cent casualty rate of illness and cancers: non-Hodgkin lymphoma was the biggest killer, followed by thyroid cancer, throat cancer, oesophageal cancer, kidney cancer, multiple myeloma, and various skin cancers. Nearly 30 per cent of the crew experienced reproductive problems, with their wives suffering stillbirth or giving birth to babies with deformities.

On 15 October 1962, another test misfired. In this test, the Bluegill Double Prime, the rocket was destroyed at a height of 109,000 feet after it malfunctioned ninety seconds into the flight. US Defense Department officials confirmed that when the rocket was destroyed, it contributed to the radioactive pollution on the island.

The following day, 16 October, the United States and Soviet Union began the ten days that threatened to destroy the planet — the Cuban missile crisis. •

This is an edited extract from Nic Maclellan’s new book Grappling with the Bomb: Britain’s Pacific H-Bomb Tests, published by ANU Press.