Printed on Stone: The Lithographs of Charles Troedel

By Amanda Scardamaglia | Melbourne Books | $69.95 | 232 pages

For years pundits have been predicting the death of print. Soon gone, they say, will be the newspapers, the weekly and monthly magazines, the comics and the fiction and non-fiction books that dominated the lives of readers for two centuries or more.

The main culprits are the advertisers who once relied on newspapers and magazines, supplemented by radio and later by TV, to sell their products. When the internet began progressively undermining print culture — most dramatically newspapers, with the Murdoch empire recently garrotting more than a hundred local titles in Australia alone — more and more advertising went online.

People who still hanker after the design, feel, smell, typography and physical presence of print will treasure Amanda Scardamaglia’s elegant celebration of Australia’s greatest lithographer, Charles Troedel, best known for his advertising and product-label designs. Printed on Stone is a beautifully designed tribute to the extraordinary output of Troedel and his artists from the 1860s onwards. With a scholarly text and meticulously reproduced images, the book traverses the commercial and imperial imagery of the era, much of it reflecting the booster confidence of “Marvellous Melbourne” before the city’s fall from grace in the 1890s depression.

Lithography, invented in Bavaria in the 1790s, involves drawing on the surface of limestone with greasy crayons. Gum arabic and nitric acid is then washed across the stone to prevent spreading or bleeding, and the ink adheres to the greasy drawing but not to the clean portions of the stone. Less costly than the traditional method of metal and wood engraving, and predating the spread of photography, lithography took off in the nineteenth century, especially as the main means of producing illustrated images for mass production. By the 1830s, multicoloured lithographs had become possible, too, using a separate stone for each colour.

Charles Troedel, born in Hamburg in 1835, became an apprentice to his lithographer father at the age of thirteen, later working in Norway and London. Recruited at the age of twenty-five for a Melbourne printing business, he arrived in the bayside village of Williamstown in February 1860. In a city growing rich on gold, he worked for a couple of years at a paper-bag manufacturing and printing establishment before setting up a small workshop in Collins Street in June 1863.

Just a couple of years later he began producing the Melbourne Album, to which readers could subscribe in twelve monthly parts. The album celebrated the prosperous city, with depictions of Collins Street’s substantial two- and three-storey structures, the grand Treasury building, the churches, the Eastern Market, later demolished, and the imposing set of terraces on Nicholson Street, which remains intact to this day. The album also included the oft-reproduced coloured lithograph of Aborigines on the banks of the Yarra, with a bark habitation and a canoe highlighted by fire and smoke.

“One People, One Starch”: Silver Star Starch poster, Troedel & Co., lithographer, c. 1891–c. 1900

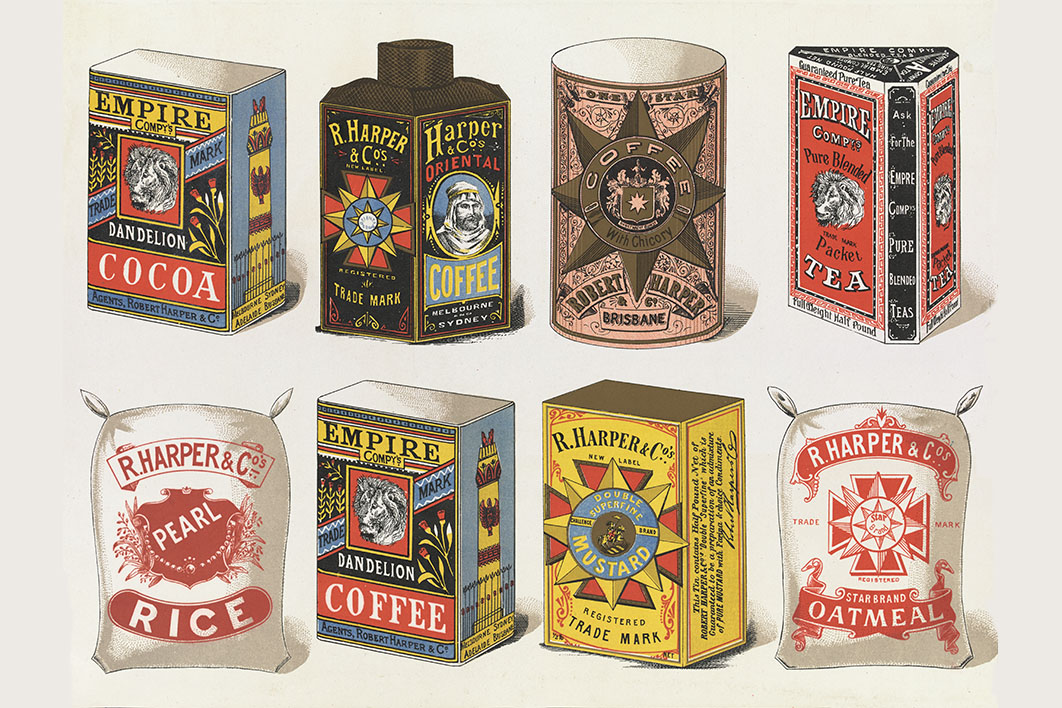

Troedel went on to make a lot of money producing crisp, elegantly designed advertising images in print and on tins. Lithographers quickly dominated the print label trade in a full panoply of products, almost always using a range of colours to good effect. Health remedies were popular: Ralph Potts Magic Balm, for instance, promised certain pain relief for troublesome kidneys and indigestion. Cigarettes and pipe tobacco were marketed using images of cricket players and gladiators, both victorious in their sporting endeavours.

Unlike the marketing and packaging of laundry starches and soap, those advertisements never featured women. But retailers had an inexhaustible appetite for fashion images, from corsets to wedding gowns. And when manufacturers came to order an advertisement they often wanted an inset image showing their grand industrial buildings, to add a sense of substance to their products.

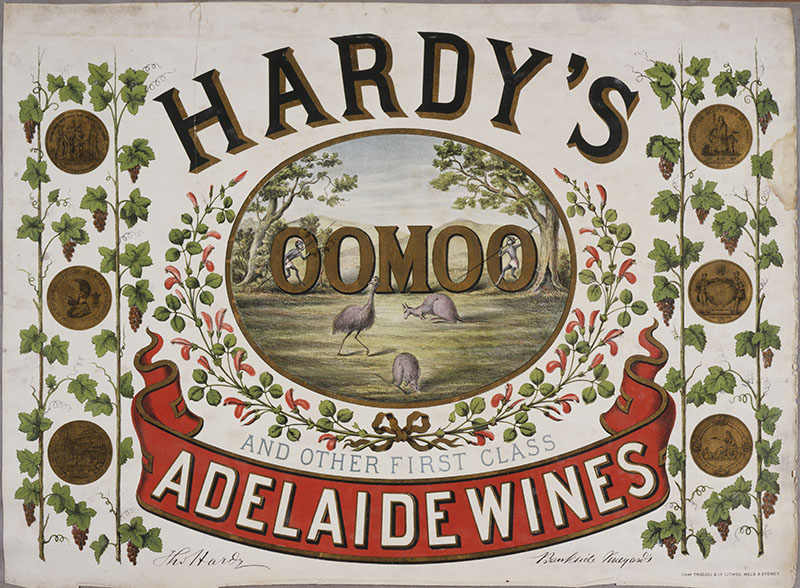

Alcohol purveyors provided a lot of work for Troedel’s firm, from importers of whisky and Jamaican rum to local manufacturers, including the Carlton, Trent and Castlemaine breweries. Some of the labels were so well designed that they have been retained to this day, including the Hardy’s Oomoo wine label (though without the words “and other first class Adelaide wines”).

“Hardy’s Oomoo and Other First Class Adelaide Wines” poster, Charles Troedel & Co., lithographer, c. 1881–c. 1900

We’re fortunate that Troedel’s business records were donated to the State Library of Victoria in 1968. This prescient act by the Troedel family created the biggest nineteenth-century print archive in any public collection in Australia. Its more than 10,000 items, including 400 advertising posters and hundreds of trade marks and labels, have been drawn on for this book.

Printed on Stone, with a foreword by a Troedel descendant, is a hymn of praise to Troedel and his company’s lithographic output. It is also a tribute to local manufacture, adopting and capitalising on European techniques. In a well-researched and accessible account of the technical, the artistic and the commercial aspects of the company, Scardamaglia explains the role that key images played in the development of commercial advertising, which she sees as a “preface” to the explosion in print advertising in the twentieth century.

“The Guard of Honour. Representing the British Army at the Australian Commonwealth inauguration, 1st January, 1901,” Troedel & Cooper lithographers

She also tackles the imperial messaging of the time, well captured in the lithograph of the Guard of Honour representing “the British Army” at the inauguration of the Australian Commonwealth. The image includes the Highland Light Infantry, resplendent in reds and tartans, the Coldstream Guards and the exotic Bengal Lancers.

Scardamaglia, a legal academic who has previously published on colonial trade mark law, has written a fine account of the work of our greatest nineteenth-century lithographer. •