Conflicted: Why Arguments Are Tearing Us Apart and How They Can Bring Us Together

By Ian Leslie | Faber & Faber | $29.99 | 286 pages

This is a self-help book for the world. Ian Leslie worries that “people with differing views seem to find it increasingly hard to argue productively.” In public debates and private disputes, “our inability to disagree well seems to act as a roadblock to progress.”

He doesn’t want to smooth over conflicts. “The only thing worse than having toxic arguments is not having arguments at all.” And he doesn’t just want people to reach agreement through compromise. He wants “productive disagreements,” the kind that “neither reinforce nor eradicate a difference, but make something new out of it.” Humans cannot aspire only to “put our differences aside,” they must put them to work.

Such work is tough. Productive disagreement, Leslie thinks, is “not a philosophy so much as a discipline, and a skill.” To help, Conflicted offers ten Rules of Productive Argument and a “toolbox” of pithy cues that add up to “a universal grammar of productive disagreement, available for any of us to apply to our lives.” Learn what is in the box and open it “when you next embark on a difficult conversation.”

Conflicted starts by making the case for conflict. It can bring us closer, make us smarter and inspire us. The strongest relationships and workplaces don’t skirt conflict: heat can bring light. Human intelligence is interactive, and disagreements enable individuals and groups to learn from each other and to “think harder about why we believe what we believe.” Artists rebel against prevailing tastes, entrepreneurs against established business models, political leaders against old injustices.

To find out how to disagree well, Leslie talked with people who make their living out of conflict. He found “remarkable similarities” between the challenges faced by professional hostage negotiators, police interviewers, therapists, mediators and diplomats, and those dealt with every day by the tyros of conflict in families, friendships and offices (where the politics is “passive aggression at scale”). The professionals are “masters of the conversation beneath the conversation,” experts at “retrieving something valuable from the most unpromising of circumstances.”

Leslie gives his ten Rules of Productive Argument a chapter each: first, connect; let go of the rope; give face; check your weirdness; get curious; make wrong strong; disrupt the script; share constraints; only get mad on purpose (as Tony Blair is supposed to have said). The final, golden, rule, the one to which all the others are subordinate, is “be real” — that is, “make an honest human connection.”

The first and the last rules draw from the same well: that is, the quality of the relationship where the conflict occurs. “Better relationships lead to better disagreements,” Leslie says. The experts are especially good at this, nudging the substance of a disagreement down the road while they mould a relationship. In a crisis, they may not have much time. Even if they are talking a stranger down from a ledge or administering first aid after an accident, they still don’t omit the first step. “It just means you need to work fast.”

Along the way, Leslie illuminates the argument and the rules with cases. Southwest Airlines in the United States built its competitive advantage by managing a specific kind of internal conflict that bedevilled airlines. Deep-seated differences over status and perceived competence among pilots, cabin crew, baggage handlers and other ground staff produced endemic disagreement that slowed aircraft turnaround times. Fixing it, and keeping it fixed, increased profits because planes spent less time on the ground and more in the air moving paying customers to their destinations.

The Wright Brothers, apparently, were “bare-knuckle debaters,” trained by their father to argue after dinner “as vigorously as possible without being disrespectful.” Wilbur thought Orville “a good scrapper.” Himself? “After I get hold of a truth I hate to lose it again, and I like to sift all the truth out before I give up on an error.”

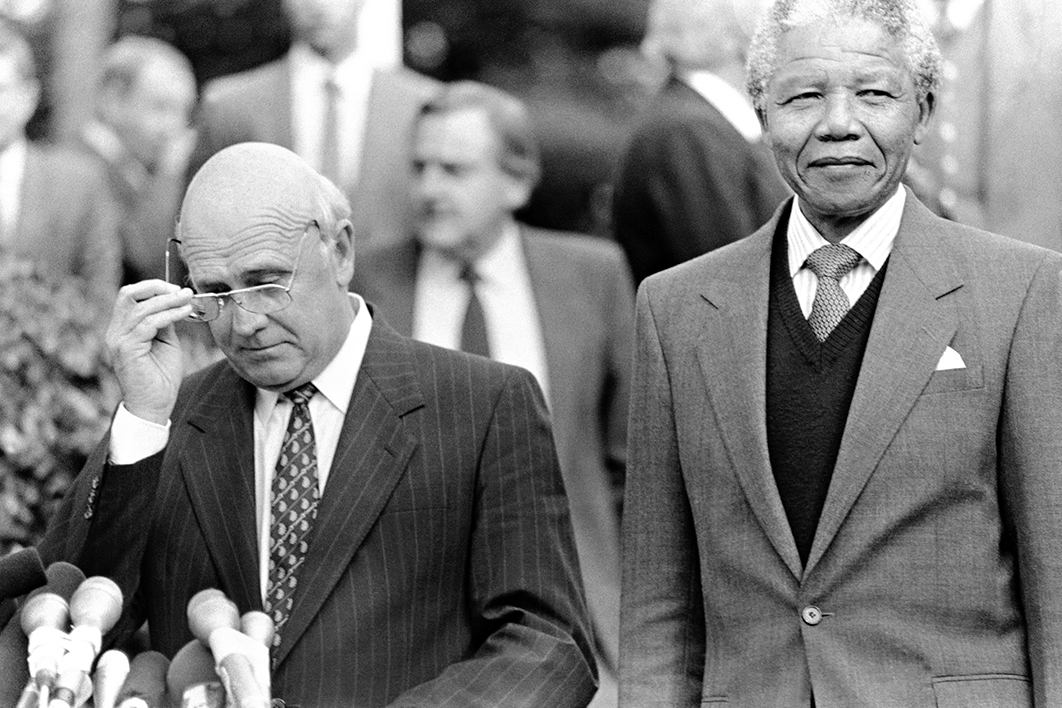

Nelson Mandela, “a genius of facework,” famously “gave face” to so many who oppressed him and other black South Africans. Leslie describes him answering the door and personally serving tea, with milk and sugar, to Constand Viljoen, “apartheid’s last best hope,” in September 1993.

In February 1993 the FBI negotiators at Mount Carmel, near Waco, Texas, brought a worldview that seemed as weird to the Branch Davidians as the Davidians’ appeared to the FBI. “They [the FBI] did everything by the book,” says Leslie. “But the book turned out to be missing a crucial chapter.” Military hardware was less terrifying to the Davidians than God’s judgement. The transcripts of “negotiation” provide excruciating evidence of mutual weirdness, unchecked, though they can also be seen as an extreme version of most human interactions. Every individual is a “micro-culture,” says Leslie; we are all “a little odd.”

“Letting go of the rope” means resisting the “righting reflex,” the urge to tell someone who is sounding a bit rattled to “calm down,” or a person who is worried by apparent trivia that “there is nothing to worry about.” In the Covid era, which hadn’t begun when Leslie’s text was finalised, it might mean resisting the impulse to tell vaccine-hesitants they are being delusional if they ask any questions about vaccines that have not received final approvals from food and drug administrations.

Leslie is a persuasive advocate for his position, and for his rules and tools, though he worries it is all too reasonable, the whole book “so… polite.” He is “not one of life’s natural warriors; even mild confrontation can make me itch with discomfort.” He knows marginalised people are sick of being told they need to be reasonable, that they need to listen to their oppressors and not just speak loudly and insistently themselves. Mandela had the muscle of international support to add to Viljoen’s tea along with the milk and sugar.

Some people really are impossible to engage with, Leslie acknowledges, but he thinks “we have a persistent, habitual tendency to overestimate the size of this group. Especially when we haven’t had much sleep.” He likes politeness, civility, ground rules for engagement, because he thinks they generally help people to disagree productively. Civility is “the minimum standard of behaviour necessary to encourage your opponent to talk back.”

It is the talking back he is after, not the civility itself. That returns him to the quality of the relationship that underpins the disagreement. “Ultimately all rules are a crutch, or a guide rail, that we can dispense with if the relationship is strong enough. We should be civil with those we don’t know, and aim to know them well enough that we can be uncivil.” •