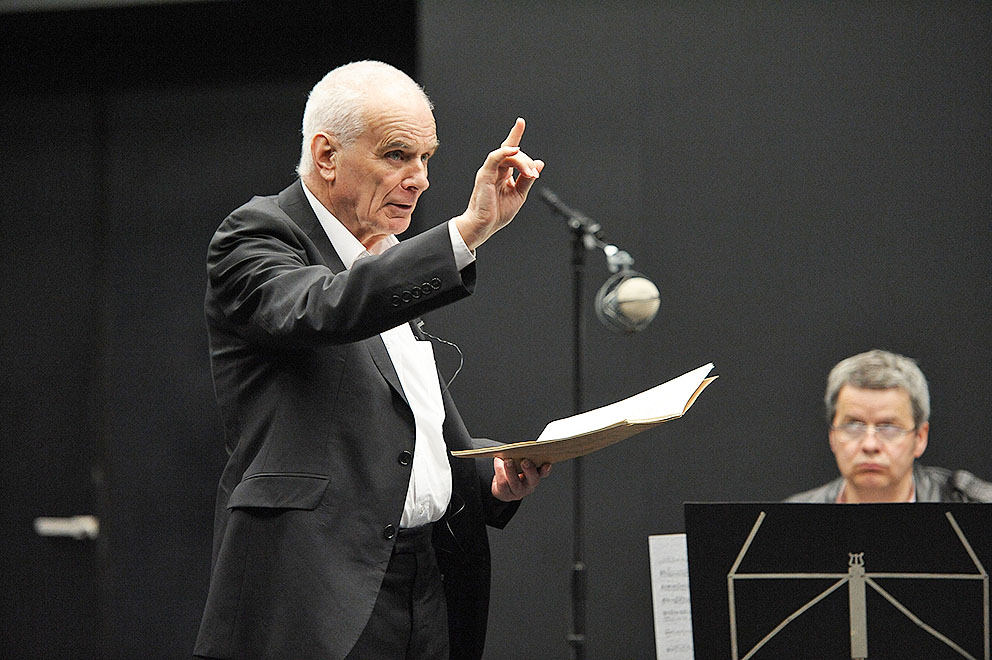

Peter Maxwell Davies, who died in March at the age of eighty-one, was the composer of operas and ballets, ten symphonies, sixteen concertos and at least thirteen string quartets, amounting to more than 300 opus numbers in all. Yet the work most often mentioned in the obituaries was one the composer himself admitted was musically “thin.”

Eight Songs for a Mad King is a classic of contemporary music theatre, its protagonist – either King George III or one who believes himself to be – surrounded by instrumentalists in giant birdcages as he shrieks, screams, wheedles and finally howls “like a dog.” In performance it is as shocking today as at its first performance in London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall in April 1969, but its substance is arguably more theatrical than musical.

Eight Songs is one of hundreds of pieces inspired, at some level, by Arnold Schoenberg’s expressionistic monodrama Pierrot lunaire (1912), in which a soprano in a Columbine costume recounts the grotesque hallucinations of “moon-drunk” Pierrot. It is hard to overstate the influence of Schoenberg’s piece. While finishing The Rite of Spring (1913), Stravinsky paused to write some songs in imitation of it, and in the century since, composers have analysed the score of Pierrot lunaire, drawn on its example, further explored its topic of lunacy, emulated its use of sprechgesang (speech-song) and, above all, composed for its pioneering mixed quintet of winds, strings and piano. During the 1960s, Peter Maxwell Davies did all these things, and with his group, the Pierrot Players, conducted dozens of performances of Pierrot lunaire itself.

It was for the Pierrot Players (later known as the Fires of London) that Davies composed Eight Songs for a Mad King. The group’s manager at the time, the Australian impresario James Murdoch, introduced the composer to a South African actor called Roy Hart, who had the rare (and possibly unique) ability to splinter his voice into complex multiphonic chords by the production of overtones. He could also sing across five octaves. The sound was never pretty, but that was not going to be a drawback in this piece. Murdoch recognised the potential for Davies’s music to become more overtly dramatic than the theatre-of-the-mind that is Pierrot lunaire. He also saw the benefits of a succès de scandale.

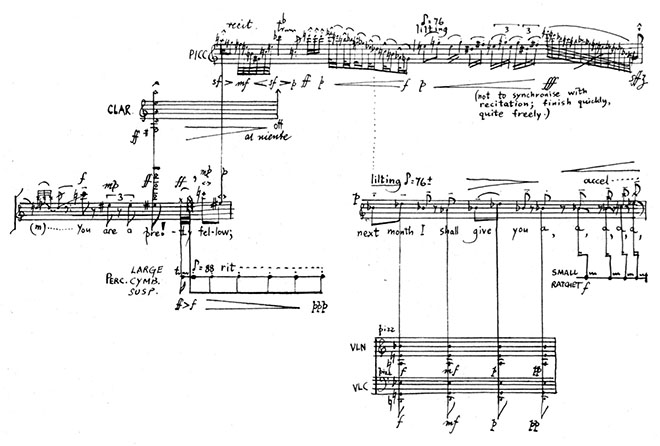

“Stage props”: part of the score of Eight Songs for a Mad King

A second important meeting also lay behind Eight Songs. This was between the composer and the historian Steven Runciman. They were introduced by a mutual friend, the poet and novelist Randolph Stow, who wanted Runciman to show Davies a small mechanical organ that had belonged to George III. It had come into Runciman’s possession along with a note explaining that “This organ was George the third for Birds to sing,” and it played eight tunes which the king had attempted to teach to his caged bullfinches. In Suzanne Falkiner’s marvellous new biography of Stow, we learn that Davies made the organ play its tunes so many times during his visit to Runciman that it never properly worked again.

Eight Songs for a Mad King quickly took shape in the composer’s mind. Stow put together a powerful libretto, drawing liberally on the diary of the courtier Fanny Burney, and Davies composed the music in a matter of weeks. Like Pierrot lunaire, the score contains a good deal of musical parody – at one point, “Comfort ye, my people” from Handel’s Messiah becomes a “smoochy” foxtrot – mocking the king’s madness. Pierrot lunaire is, among other things, a textbook of rigorous contrapuntal writing – you could replace the voice with another instrument (an oboe, say) and it would still be a fine piece of music. But Davies’s score is what the composer himself described as “a collection of musical objects… functioning as ‘stage props,’ around which the [actor’s] part weaves.” The third song – a duet with the flute – is notated to resemble a birdcage, the king’s music forming the vertical bars while the flute’s notes are written horizontally.

But how should one “sing” Eight Songs? Hart, who died in 1975, was able to produce sounds that have proved impossible for other singer/actors (we can hear a bootleg recording of his performance on a CD obtainable from roy-hart.com). Since there was no standard notation to represent Hart’s vocalisation, Davies often resorted to illustrative shapes and squiggles and verbal descriptions (“like a horse” is one), leaving the piece open to a greater range of interpretation than might otherwise have been the case.

Davies recorded the work in the studio with the American singer and composer Julius Eastman, who also performed the work in concert with Davies (and others, including Boulez and members of the New York Philharmonic). But Eastman sounds very different from Hart. Sometimes they are in completely different parts of their voice, and Eastman never really succeeds in producing multiphonics. In Gay Guerrilla, a recent collection of essays about him, several writers point out that Eastman’s mad king was his greatest claim to fame, but none of them thinks to explain his approach to the work.

Peter Maxwell Davies expected Eight Songs for a Mad King to be a flash in the pan. Perhaps that’s why he didn’t devote much time to its composition or try seriously to codify the notation of its vocal part. But not only did it become his most famous work, it soon established itself as a baritone’s party piece, and it is partly the vagueness of the notated score that encouraged that. The work has now been performed many hundreds of times, and numerous solutions have been found for the staging – sometimes leaving out the birdcages. By the same token, each new singer has had to find his own voice, his own king, his own vocal madness, inspired by the clues and hints in the composer’s handwritten score. •