The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s

Peter Doggett | Bodley Head | $32.95

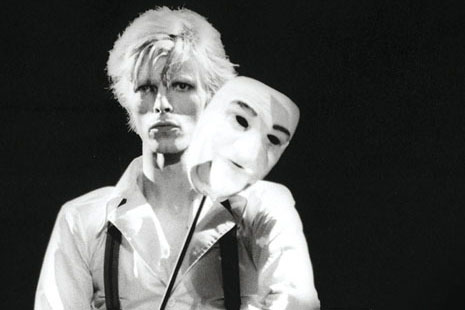

THE ostensible theme of Peter Doggett’s splendidly written book is the evolution of the mod-mannish-boy David Jones of the sixties to the multiform chimera David Bowie of the seventies. But thankfully this is not the familiar, well-trodden narrative of Bowie criticism that describes a cultivated act of post-renaissance self-fashioning, with its list of improbable dramatis personae of Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane and the Thin White Duke. Doggett filters this process of becoming through a chronological account of the development of Bowie’s music from 1969 to 1980. This canny approach allows Doggett to capture the morphology of Jones/Bowie as an artist who soaked up what was going on around him, and in turn vamped the cultural DNA that made the transition from the swinging sixties to the glam, proto-punk seventies possible.

There is something inherently appealing in this kind of close textual analysis that weaves a bio-social narrative out of the compositional detail of specific songs, as well as the way individual songs work together to form a suite or narrative on any given album. A snippet from an account of an unreleased song (“Rupert the Riley”) written by Bowie for Mickey King’s All Stars and recorded during the Ziggy Stardust sessions, captures the sharp, contextual economy of Doggett’s style:

Like all good car songs, it carried some sexual innuendo, but its intention was merely to amuse. Bowie hoped that it might spawn a musical career for his friend Micky “Sparky” King, a rent boy whom he and his wife had met at the gay mecca of the Sombrero Club in Kensington. (“I would try and get anyone who would open their mouths to do my songs,” Bowie recalled in 1998.) In the event, the track wasn’t released, but it lingered in Bowie’s memory: its “beep-beep” chorus (borrowed from the Beatles’ “Drive My Car”) not only reappeared in “Fashion,” but was probably the melodic ancestor of the “transition/transmission” refrain in “TVC15.”

In a break-out commentary (a feature of the book that keeps the biographical narrative flowing throughout and integrates the discussion of the individual songs) Doggett completes the link between song, album and stage in Bowie’s emergence as Ziggy: “His star would be, in the jargon of the advertising industry, a ‘trade character,’ a brand so powerful that it would demolish everything in its path. And it would arrive fully grown, already invested with the glory that lesser mortals – such as David Bowie – could spend precious years trying in vain to achieve. Bowie would be creating not just a star, but a guaranteed route to stardom.”

At his best Doggett’s writing in this respect compares favourably with Nick Tosches’s authoritatively hip Unsung Heroes of Rock ’n' Roll: The Birth Of Rock in the Wild Years Before Elvis (1991). Doggett’s part-for-whole strategy of drawing a larger narrative from individual songs (rather than albums) also has affinities with Greil Marcus’s 2005 picaresque account of the recording of Bob Dylan’s song “Like A Rolling Stone.” And his capacity to tell a story of evolution and transformation, the hullabaloo of who took what and who was having sex with whom is certainly far more compelling than Robert Greenfield’s promising but blandly written 2006 book on the recording of the Stones’ Exile on Main Street.

The Man Who Sold the World may well be received as just another book on Bowie (in the same way that Mick Wall’s 2008 When Giants Walked the Earth is just another book on Led Zeppelin, despite its author’s insistence on being an intimate of the band, with his hokey and ultimately irritating second-person mode of address: “You are Jimmy Page. It is the summer of 1968 and you are one of the best-known guitarists in London”). In terms of the book’s place within Bowie discourse, Doggett certainly pays his dues and acknowledges the plethora of writing on his subject that precedes him, in particular Mick Rock and Bowie’s collaborative Moonage Daydream: The Life and Times of Ziggy Stardust (2002), which authoritatively documents in word and image the ascendance of Ziggy and his alter egos. Doggett happily acknowledges, however, that the “unashamed model” for the song-based focus of the book is Ian MacDonald’s 2005 book on the Beatles, Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties. He is especially careful to cite contemporaneous studies such as Paul Trynka’s 2011 biography Starman and Kevin Cann’s Any Day Now: The London Years 1947–1974 (2011).

The latter titles are in fact representative of a conspicuous flurry of books on Bowie over the last ten years, not to mention his repertory presence in classic rock mainstays such as Mojo and Uncut (Doggett was the lead essayist in a special “limited” 2003 edition of Mojo devoted to Bowie). It would be naive to presume that such ongoing attention to Bowie is in any way singular or distinctive. But there is something conspicuous about the staying power of a very specific period, tone and poetic engagement with the evolution of the artistic self and its relation to culture. Of the book’s structure, in this respect, Doggett is forthright at the start of the text, providing a taste of the louche journey we are about to take: “Interspersed among those song-by-song studies are brief reviews of every commercial project Bowie undertook during this time frame: and short essays on the major themes in his work and times, from occult to glam rock, fashion to fascism.”

THE vexed question of rock and pop demography can’t be avoided in discussions of music recorded forty years ago, in what is now nostalgically or cynically called, depending on who and when you are, the age of “classic rock.” For Homer Simpson, rock music unquestionably reached its sublime apotheosis in 1974, after which nothing of any consequence could possibly follow (Nine Inch Nails are among the many “no name” bands he is puzzled by). But such baby boomer arrogance clearly holds no truck for generation whatever letter of the alphabet we are currently up to.

An example illustrates this point, and also underlines the significance of publishing a book on Bowie like Doggett’s in 2011. A number of years ago my colleague Niall Lucy and I submitted a book proposal to the 33 1/3 series published by Continuum in New York. 33 1/3 books are small format, fit-in-the-back-pocket studies of individual albums of significance from the last fifty years of popular music (titles such as Live at the Apollo, OK Computer, Ramones, Abba Gold and Piper at the Gates of Dawn suggest just how eclectic the “popular” is). Now the question of what and for whom an album is “significant” is very much at the heart of this example. Our pitch for The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, which we regarded as an album of some significance that would complement the 33 1/3 back catalogue (Bowie’s Low had been added to the list in 2005), made the final cut of twenty-seven out of more than 400 submissions received by the publisher in 2009. As we checked for updates each week the discussion on the 33 1/3 blog, which was feverishly engaged in debate over the relative worth of the shortlisted submissions, became very heated along demographic lines. Neglected bands such as Ween were seen to be eminently preferable to yet another book on a dinosaur of 70s glam rock (the series’ seventy-ninth title, on Ween’s 1994 Chocolate and Cheese, was published in 2011). Our Bowie submission was seen by one blogger as an instance of the “old guard rearing its ugly head,” of the publisher’s opting for what would appeal to the broadest possible market rather than taking risks with less mainstream, underground and experimental bands.

For whatever reason in this instance, Ziggy didn’t play guitar. It is pleasing then to see him step on to the stage once more in Doggett’s unapologetically musicological study (and one, he is quick to qualify, that it is very much a layman’s approach attentive to the general reader equipped with a “limited knowledge of musical terminology”). The Man Who Sold the World persuasively and astutely demonstrates that cultural moments or eras are never fixed and completely known, and argues that the deeper significance of a particular cultural moment (the sixties, the nineties, and so on) can’t be fully seen and heard for what it is until after the fact. As Doggett asserts in his introduction, no other pop artist took as many risks as David Bowie, none “so obsessively avoided the safety of repetition, or stretched himself and his audience so far. Little wonder, then, that it would take the following decade for Bowie, and his contemporaries, to assimilate everything that he had achieved, and move beyond it.” •